Kathy Iovine, an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, and Bob Skibbens, a Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, introduce you to their research on Roberts Syndrome. This work is funded in part by a Faculty Innovation Grant.

Greetings! The purpose of this post is to introduce you to a Faculty Innovation Grant titled Developing a vertebrate model system for Roberts Syndrome. Roberts Syndrome (RBS) is a severe form of birth defects that significantly impacts bone growth (as well as cognition and organ development). In RBS patients, the long bones of the limbs are severely reduced, along with craniofacial abnormalities (cleft palatte, small head size, etc). The syndrome arises due to mutations in a gene named ESCO2, but the basis of the ESCO2 defect remains unknown. An important step forward will be to develop a model system for RBS so that we can ultimately devise clinical therapies.

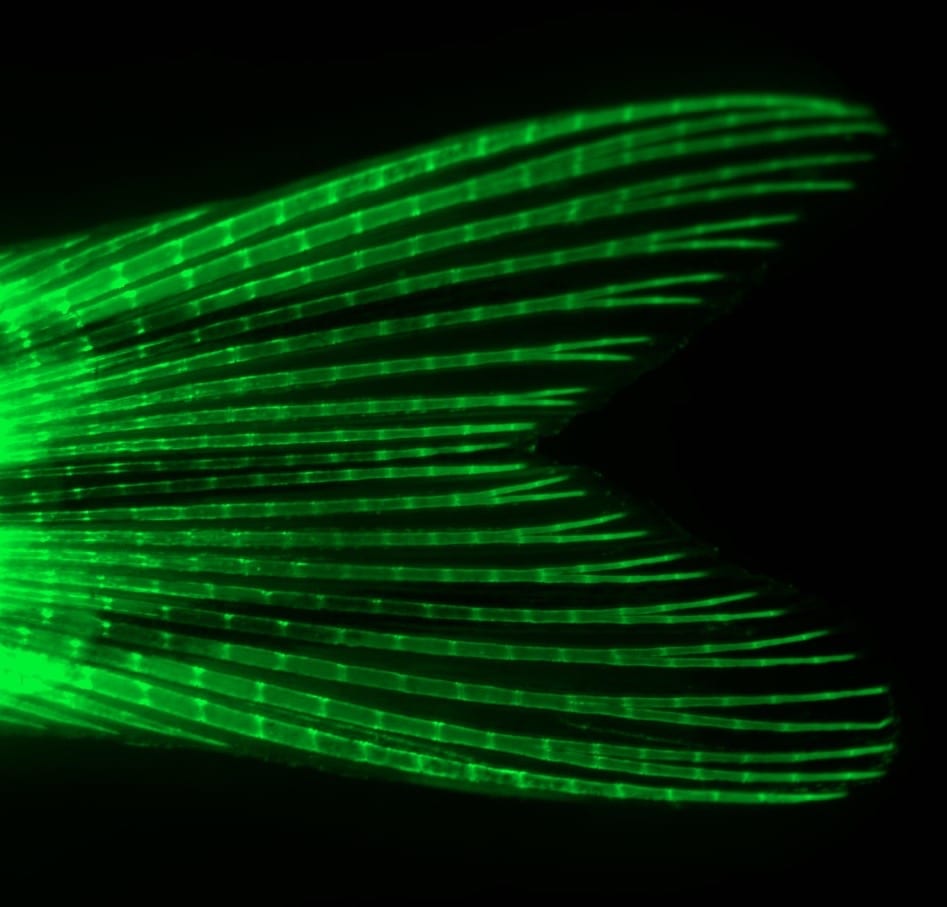

As part of a collaboration between the Skibbens and Iovine lab groups, we are establishing the zebrafish fin as an RBS model system. Zebrafish fins are an excellent system since amputation results in complete regrowth, and we have the technology to turn down gene function during regrowth (“regeneration”). We found that loss of Esco2 protein causes skeletal defects in the zebrafish regenerating fin (Figure 1 shows a normal fin skeleton). With the ability to assay for Esco2 function in regenerating fins, we are pursuing a new model that Esco2 may cause skeletal defects by regulating the expression of genes. Evidence obtained through this collaboration suggests that Esco2 regulates cs43 – a gene that encodes a protein previously shown by the Iovine lab to impact bone growth (check out Iovine et al., 2005, Developmental Biology) and implicated in a developmental abnormality referred to as Oculodentodigital dysplasia. This research has been published in the journal Developmental Dynamics (Banerji et al., 2016 Developmental Dynamics)!

More recent efforts have been to provide mechanistic insights into how Esco2 regulates the expression of the skeletal gene cx43. The most direct way to show this is to demonstrate that the Esco2 protein, or a protein regulated by the function of Esco2 (i.e. Smc3), associates with the cx43 gene. Esco2 regulates the ability of Smc3 (and others) to associate with DNA. We are now testing if Smc3 physically binds to the DNA surrounging the cx43 gene. Raj Banerji has made important progress showing that she can isolate chromatin (i.e. genomic DNA plus all of the associated proteins) from a fin cell line, AB9. She can also isolate only the parts of the chromatin that are associated with Smc3. She is now testing if cx43 DNA is among the isolated Smc3-bound chromatin.

Keywords: skeletal disease, zebrafish, regeneration, gene expression

a PhD. In addition to seeking out the archives at Humboldt University (formerly the University of Berlin), I was also asked to present my research to a group of graduate students at the University of Potsdam. At the invitation of Professor Logi Gunnarsson, an expert on James’s work, I was able to share the influence of James’s teaching on the young Du Bois, as we navigated James’s 1890 text “The Hidden Self.” The dialogue and feedback was wonderful. And I made an invaluable friend and colleague in Logi. We often forget how influential German intellectuals were in shaping the American academy. James and Du Bois were no different. It was truly exciting to be in this formerly divided city, thinking about race, the subconscious mind, and double consciousness, all with young men and women eager to complete their own graduate education and share their perspectives on a topic that clearly crosses the Atlantic in terms of importance. I look forward to returning to Cambridge to learn more about James and Du Bois at Harvard – but also one day to Berlin – and to Potsdam – to revisit the same field of study that so shaped these two critical thinkers in American race and psychology.

a PhD. In addition to seeking out the archives at Humboldt University (formerly the University of Berlin), I was also asked to present my research to a group of graduate students at the University of Potsdam. At the invitation of Professor Logi Gunnarsson, an expert on James’s work, I was able to share the influence of James’s teaching on the young Du Bois, as we navigated James’s 1890 text “The Hidden Self.” The dialogue and feedback was wonderful. And I made an invaluable friend and colleague in Logi. We often forget how influential German intellectuals were in shaping the American academy. James and Du Bois were no different. It was truly exciting to be in this formerly divided city, thinking about race, the subconscious mind, and double consciousness, all with young men and women eager to complete their own graduate education and share their perspectives on a topic that clearly crosses the Atlantic in terms of importance. I look forward to returning to Cambridge to learn more about James and Du Bois at Harvard – but also one day to Berlin – and to Potsdam – to revisit the same field of study that so shaped these two critical thinkers in American race and psychology. a PhD. In addition to seeking out the archives at Humboldt University (formerly the University of Berlin), I was also asked to present my research to a group of graduate students at the University of Potsdam. At the invitation of Professor Logi Gunnarsson, an expert on James’s work, I was able to share the influence of James’s teaching on the young Du Bois, as we navigated James’s 1890 text “The Hidden Self.” The dialogue and feedback was wonderful. And I made an invaluable friend and colleague in Logi. We often forget how influential German intellectuals were in shaping the American academy. James and Du Bois were no different. It was truly exciting to be in this formerly divided city, thinking about race, the subconscious mind, and double consciousness, all with young men and women eager to complete their own graduate education and share their perspectives on a topic that clearly crosses the Atlantic in terms of importance. I look forward to returning to Cambridge to learn more about James and Du Bois at Harvard – but also one day to Berlin – and to Potsdam – to revisit the same field of study that so shaped these two critical thinkers in American race and psychology.

a PhD. In addition to seeking out the archives at Humboldt University (formerly the University of Berlin), I was also asked to present my research to a group of graduate students at the University of Potsdam. At the invitation of Professor Logi Gunnarsson, an expert on James’s work, I was able to share the influence of James’s teaching on the young Du Bois, as we navigated James’s 1890 text “The Hidden Self.” The dialogue and feedback was wonderful. And I made an invaluable friend and colleague in Logi. We often forget how influential German intellectuals were in shaping the American academy. James and Du Bois were no different. It was truly exciting to be in this formerly divided city, thinking about race, the subconscious mind, and double consciousness, all with young men and women eager to complete their own graduate education and share their perspectives on a topic that clearly crosses the Atlantic in terms of importance. I look forward to returning to Cambridge to learn more about James and Du Bois at Harvard – but also one day to Berlin – and to Potsdam – to revisit the same field of study that so shaped these two critical thinkers in American race and psychology.