One of the most important tasks of the compositional process was dividing the poem into smaller sections and placing each of these sections into a single word document with a temporary song title, then printing each page. Since Beachy Head is so large, having 26 separate pages allowed Amanda to carry the poetry with her in a folder everywhere she went, because she never knew when melodic and compositional ideas would strike. These hard-copy pages allowed her to make notes and ponder Smith’s words.

Whenever Amanda works with great poetry, her compositional process involves reading and re-reading a poem. Through this process, she looks for nuance in the words and their relationships to each other. As she does this, she simultaneously listens for a wisp of sound within her mind and identifies the emotions a poem evokes. These ingredients are necessary to compose, and how she translates poetry into Art Song. Once she hears the suggestion of sound and emotion, she is able to write a piano sketch of the lyrics and a description of the sound.

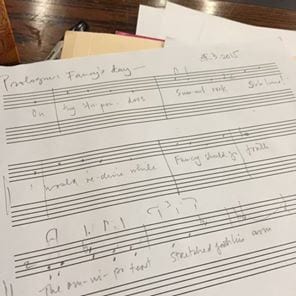

Using a mechanical pencil, she writes a single line of music with lyrics on a piece of manuscript paper with potential harmonic progression. From there, she places the song into a computer-generated sketch with room for piano accompaniment and then works the song to its completion. When she would stall in the process, she would discuss the moment with Beth. This gave Amanda more information and understanding about the poem, which was derived from Beth’s knowledge, and aided the compositional process. Through these interactions, sometimes words would be returned, at others, words would be taken away; it depended on the song and the moment.

Throughout the entire compositional process, Amanda let Smith’s poem lead her. With Beachy Head she was always surprised by where and when the poem led her to the music. For example, she still marvels that “Shepherd on a Hill” was composed on a red-eye flight from Seattle to Newark. “Hind’s Wife and Children” she heard from beginning to end one afternoon in Boston when she was working on a musical at Boston College. She picked up the sheet of poetry and heard the song.

Over a process of two years, the 26 art songs emerged, with leit motif (e.g., “Beachy Head,” “Happiness,” “The Stranger”) spread throughout all the songs. The leit motif serves to unite the cycles. While in the tradition of Romantic song cycle, the expanse of “The Songs Cycles of Beachy Head” is of greater size and scope than Schubert’s “Winterreise” (24 songs) or Schumann’s “Dichterliebe” (16 songs). Both of these famous song cycles come from sets of poems instead of a single poem.

As a performance piece, the flexibility of “The Songs Cycles of Beachy Head” is remarkable. The 26 songs divide into five interdependent song cycles and can be performed as one massive song cycle, or one of the the five cycles can be performed independently. These two aspects make “The Song Cycles of Beachy Head” a unique and substantial contribution to the art song cycle canon.