Growing up, I watched, young and impressionable

as my father battled his demons. Sometimes

he heard them in my mother’s voice, saw their shadows

hiding under their wedding rings, those were never quiet

nights in the house. When the first boy to love me

asked why I wouldn’t love him back

I saw in his face the brown eyes of my mother,

aged and jaded, the need to fix me was freckled

like specks of his golden heart were misplaced

in his eyes. He begged me to love him and I heard

my mother’s tired voice repeating her vows, selfless

soul turned martyr for sinner. I returned the love

letters, weathered keepsakes I didn’t deserve

because in his hands I could only see chains

for my neck, hugs were jail cells and kisses poison,

his tongue twisted compliments into arguments.

In him I could see the reflection of my flaws

and they looked like my father.

All posts by dib222

Pygmalion Principle

if I squinted hard enough,

I could pretend I have rose-colored glasses

and be swept away by the shoddy love song written

on the back of his notes, passed to me between classes.

maybe I could perfect my laugh

and be the one-woman audience to his Shakespearean

comedies, alligator tears for his imitation tragedies.

I’ll write myself sweet nothings in his handwriting

between the lines of his drunk compliments

great tits, nice ass, built like a pornstar.

as he dances around his intentions

and I meet his clumsy waltz with smooth steps,

I’ll woo my reflection in his name

for a fairy tale romance with a thorny beast.

I learned to cross my eyes to keep his flaws

out of focus, steadying myself on the fuzzy fading

of his face. Maybe the headaches could be symptoms

of infatuation, if I could just convince myself.

Maybe he could be better than the last time

I forced a weed to look like a flower.

Black Eyed Bell

Trigger Warning- Sexual Assault, Domestic Abuse

The boxing bell echoes in the quiet

while his hands, those rugged and freckled

buckets for cinnamon whiskey and beer,

boxing gloves that always strike,

nestles the bottle opener against his next drink,

the last still half full, stale and warm,

and his opponent slumps against the suede cushion

that marks the boundary of their ring.

The rusty bell sings to her battered ears

like the distant, warbling chirps of early morning blackbirds

and she wonders if they can hear her too.

The bells confess the end of another round

but the hits have left her lips bruised, eyes swollen

with tears. Disoriented she finds another round thrust

upon her.

She cannot feel the words that slip and slide

down the tip of her tongue to land at his feet

Is it blood or spit or dignity

that she’s dropped? Will he make her clean

the bits of herself that spill out in the fight?

Those creeping, speckled hands tighten around the neck

of the bottle, push the smooth glass into her hand

gentler now, she’s surprised by the change in tactic

and falls into his trap. Another sip decides the match.

The knockout tastes almost as bitter as his lips.

Hangover Letter

Last night she asked how you were as your eyes rolled back,

slumped against the loveseat, leather jacket a makeshift blanket

over your barely clothed chest. She expected an answer be it

laughter, rolling off the couch, asking for water, a mindless noise even.

You stared at her. White-hot static buzzing in your brain instead

of words. A thumbs-up sufficed to say everything was okay.

She walked you home in the middle of the night, streetlight

ambiance and the cool night air of summer fading to autumn.

Despite her warnings, you said hello to the strange man wandering

but you felt he was a kindred spirit, incapable of posing a threat

because the world, though dark, was rosy pink last night.

When you stopped to sit in the grass, she stared and asked

for the third time that night if you were okay. This time

you smiled, the toothy, gum bearing smile you saved for real moments

of bliss, the smile that exposed all your teeth were straight except

those front two, one crossed over the other just slightly and you answered

I think I love her and I’m okay with that and she laughed, picked you up

by the arms and walked you home in silence.

My Mother Asked Why I Won’t Call My Grandfather

Maybe I’m just afraid of aging,

not for cosmetic reasons, I’d rather

have a wrinkle over a pimple on my face.

It’s the uncertainty of the far future. I know

the lavender bush will bloom next season,

but will she last the next five years? Ten? Forty?

I see in my grandfather the grip of time,

I could accept the greying hairs, but now

they recede and leave his head bare.

I worry he needs a hat to keep warm

and to keep the memories neatly where they belong.

I worry that it won’t be long

until my grandchildren have the same fear.

I’d rather die young, forty in a mysterious incident

or thirty-five in the ocean, saltwater flooding

my lungs because I never learned to swim

from my grandfather. I’d rather die young

than live long enough to know that my babies

fear the day I might forget them. I’d rather die

young than watch my grandchildren wait for me

to become a caricature of loneliness, the familiar

features of my youth faded into a new face. I’d rather die

clueless to the way their hearts break seeing me

grow old and frail and grey, teary-eyed goodbyes

because they think each day with me is a miracle.

I’d rather die than become a stranger in their mother’s casket.

If God Was a Woman

She’d love Mother Nature so sweetly

Spring would last an eternity, the trees

swaying their branches to the tempo

of their wedding song, Hummingbirds

orchestrating a ballad for the ballroom

made of marigolds. She’d tuck sunsets

into Mother Nature’s pockets, vows

beyond words, love notes written

in the ink of the clouds.

Over a moonlit dinner, with their plates

of sweet mulberry sky, wine glasses of deep

ocean Cabernet, Mother Nature would confess

she hated the color grey, and God, sweet as can be,

would dismiss the dreary shades of life if only

to momentarily please her wife.

She wouldn’t let their daughters be fooled

by vanity, artificial wide eyes from lacing

their own wine with belladonna to attract the men

distracted by the folly of glory

and pride, she wouldn’t watch from her garden

as her children tore themselves apart.

She couldn’t make us pick

to live or to feel alive

because she loves her children too much,

an aching love, a tears-spilled-for-their-mistakes

love. Her forgiveness would be rosy pink, like the flush

skin of her sinners. She’d tell us the sin of skin

is forgetting to indulge.

Dexter: The Rainbow of Harrison Morgan

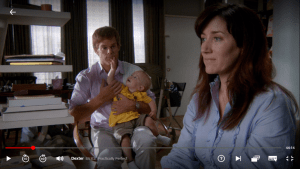

Purposeful color choices in the show, Dexter, often reflect the mood of the scene, setting the tone for the audience to interpret and enhancing the subject at hand. These color choices often reflect the turmoil of the show’s protagonist, Dexter, relating to his life, his past, and his thoughts. The creators utilize lights to often convey these important themes but also use the characters surrounding Dexter to point out recurring motifs and parallel Dexter. One of the most important examples of this is Dexter’s son, Harrison. Using Harrison as a mode of conveying color in the show allows the creators to parallel Dexter’s past and illuminate the issues that Dexter faces in his attempts to become a father. Harrison’s presence contributes an essential piece to the importance of noting color in the series because Dexter’s son is the prime candidate to reflect how Dexter struggles with maintaining his family and his need to kill without overlap, and ultimately his failure to do so.

Harrison’s presence in season four is the catalyst for Dexter’s struggle to balance his life as a father and his life as a serial killer. While having already taken the role and acted as a father figure to Cody and Astor, having his own biological son produces a new concern for innocence in Dexter. In episode one of season four, “Living the Dream,” Dexter struggles with balancing fatherhood, getting sleep, and chasing his next victim. He seems to overcompensate as a father, constantly insisting to Rita that he can take care of Harrison in the night, even when it leads to his over-exhaustion. In one of the scenes where Dexter takes care of Harrison in the middle of the night, his lines introduce the theme of innocence that becomes tied into Harrison’s character. “I’ve already lost my innocence. I’m not going to sacrifice yours too” (s. 4, ep. 1, 41:10). Dexter is committed to protecting all his children, but there is a closeness with Harrison that isn’t depicted in his relationships with Astor and Cody. These lines are a promise to Harrison directly as he cradles his son in the night and there is an intimacy between the two of them as Dexter finishes confessing the truth about himself to his infant son. The implication of Dexter’s words in a literal sense refers to when he was “born in blood” and lost his innocence. However, the message extends beyond this dark meaning and Dexter uses it to justify his killing to protect his son. Season four follows the imbalance between Dexter’s commitment to his family and his desire to continue pursuing the Trinity Killer. This imbalance ultimately leads to Dexter breaking his promise to Harrison and introduces the first scene where color choices regarding Harrison reflect on and parallel Dexter.

In the final moments of season four, Dexter’s wife Rita is killed at home with Harrison. Her death is thematic in that it involves gruesome amounts of blood all over the bathroom and leads to Harrison’s “second birth.” When Dexter returns home, he discovers the Trinity Killer found his family and killed his wife, leaving behind Harrison in the scene depicted below. Dexter’s son is covered in his mother’s blood, crying and alone. It is important to note that he is also dressed in lighter, pastel colors ruined by the darkness and stain of his mother’s blood. This scene strongly parallels Dexter’s own birth in blood, as he sits crying in blood until his father comes in to grab him and take him away from the scene. Blood is crucial in many aspects of Dexter’s life, from his profession to his darker choice in pastimes, but he attempts to compartmentalize these aspects of his life and keep them away from his family, especially his son, Harrison. However, in this scene, the choice to parallel how Dexter was “born in blood” and covering the pastel wearing child in the deep red of blood reflects Dexter’s failure to be a good father and protect his son and his family. This is the loss of innocence that then catapults Dexter to feel concerned for Harrison’s future behavior in season five.

Season five reflects the timid approach to fatherhood that Dexter takes as a single father after Rita’s death and his growing concern for Harrison’s behavior. He worries over the innocence of his son, seeking to find him an appropriate nanny while also being concerned over his behavior and overanalyzing typically childish behaviors. His concern over the season is primarily focused on the darkness inside of himself and potentially inside of Lumen Pierce and Harrison. However, the screenshot below from episode three shows that while Dexter worries over his son’s darkness and his ability to take care of him, Harrison is still an innocent child, capable of being the light in Dexter’s life. In a scene where most of the room is just average, mostly white or light-colored, Harrison’s yellow shirt is the focus of the scene, making the color emphasis more poignant. Yellow is a warm, bright color that inspires and is associated with sunlight, optimism, and happiness. The decision to put Harrison in this color intentionally sets him as the light and brightest spot in Dexter’s life at this moment after losing his wife and his other two children, who choose to live with their grandparents. However, it does not stop Dexter from worrying that this “brightness” in his son hides a dark passenger. He acknowledges his concern in episode five after Harrison scratches another baby. “Is there darkness in Harrison or is it just my own fear being reflected back?” (s. 5, ep. 5, 48:48). The juxtaposition of Harrison in yellow, defined as the brightest aspect of Dexter’s life, and the underlying concern that he is developing a dark passenger once again reflects how Dexter worries that his son may be on the same path as him. This is another moment where the color choice reflects the parallels between Harrison and Dexter while also illuminating his struggle to cope with fatherhood.

Season six marks Dexter’s newest attempt to do what is best for Harrison, despite not agreeing with some aspects. He enrolls his son in a Catholic preschool, despite his own status as an atheist. Religion becomes a component in this season and Harrison is dressed as a lion in the scene. The lion is the top of the food chain and the scene is ironic because Travis Marshall is sacrificing a “lamb” to his god. In this scene, in particular, it is important to notice not the colors in particular but the costuming, similar to specific color choice. Harrison and Dexter both wear masks in this scene, paralleling the motif of masks that has been evident and recurring since the first season. Once again this mirrors a similarity between Harrison and Dexter. It should also be noted that Harrison is the only child wearing his mask. The others have hoods, or the cow is lifting his mask, but instead, Harrison is once again mirroring his father and keeping his mask on in front of others. This intentional costume allows for the creators to foreshadow that even as Dexter seeks to protect Harrison from the darker world, it will likely be that his innocence will be taken, and he will develop a mask. Later in the episode, Harrison is abducted and nearly sacrificed by Travis Marshall, but without his mask the viewers can see that he is still a young boy crying and that this scene will likely be scarring on his subconscious.

In season eight, the thematic choices of yellow, red, and white come together to reflect Dexter’s inner turmoil and his struggle to be a father and killer and keep his son’s innocence intact, the recurring idea in each season that Dexter interacts with his son. In the opening moments of season eight, Dexter’s monologue conveys how well he and Harrison are doing after LaGuerta’s death, demonstrating at the same time scenes that convey that the two have been bonding in the six months. The uniform for Harrison’s team is yellow and Dexter wears the same color, shown in the screenshot here from episode one. Dexter begins the season overtly positive, reflecting on his time with his son with affection and this scene reflects that. This is the return of the color yellow, which once again is intentional. However, this time it is Dexter and his son that are both wearing the color, suggesting that Dexter is hopeful and in a good place at this point of season eight. In the monologue, Dexter explains that he has been involved with numerous activities from being a loving father to having an active love life and also pursuing his dark pastime. Thus, the color choice here reflects that Dexter seems to be hopeful and optimistic about his future, just as Harrison seems to be an optimistic and happy child in this scene, paralleling his father’s attitude. However, this positive outlook is not one that lasts for the rest of the season, as Harrison is covered in blood and near the color red in multiple scenes, each reflecting a new but similar view.

Season eight begins hopeful for Dexter and Harrison, but as it progresses, it seems that Dexter becomes reckless and it is reflected in how Harrison is portrayed in relation to colors and blood. Dexter, infatuated with Hannah McKay’s return, becomes reckless and makes decisions that endanger Harrison or threatens his innocence once again. In episode six, Dexter finds that Harrison keeps an incriminating piece of evidence: his white Puppy with blood on it. The white puppy is symbolic of Harrison’s innocence, the one thing that Dexter has attempted to protect since his birth in season four. It has been a struggle for Dexter to maintain and protect Harrison, but at this point, Harrison appears a normal boy. However, now Dexter has taken Harrison to a crime scene and corrupted his son’s favorite toy, and thus his son because, at this age, Harrison’s cognitive skills and memory are better developed than when Rita died. The stuffed animal is stained red with the blood of a man, marking the turning point in the relationship with Dexter and Harrison. This is the first mistake that Dexter makes that seems to have consequences on Harrison. Despite that his son doesn’t understand it is blood, Dexter has messily involved his son in his darker activities because he reacted recklessly. The colors in this scene symbolize that Harrison’s innocence is now threatened by Dexter’s life. His role as a father is now far more complicated because Harrison is at an age where every detail could potentially imprint itself in his subconscious. This moment foreshadows how Dexter ultimately hurts the innocence of Harrison in the series finale.

There are numerous other scenes that reflect this same idea of Harrison being tainted and ruined by the color red. In episode ten, Harrison injures himself on the treadmill at Debra’s house and Hannah takes him to the hospital and his shirt and towel are soaked in blood. However, this scene pales in comparison to how the creators dressed Harrison in the final moments of the series. Dexter abandons his son with Hannah McKay, leaving his son to grow up without either of his birth parents and under the impression that his father is dead. Hannah McKay is dressed in all black, appropriate for mourning the assumed death of Dexter Morgan. However, in this scene, Harrison’s red shirt is visible under his jacket. At first, it appears as a normal choice in wardrobe, but everyone else in the scene is dressed in all black or white, making Harrison the most colorful. Considering how Harrison’s most important scenes show him in bright, lighter colors, this decision to dress him in red where everyone else is in black or white makes him stand out. It also reflects in the final moments how his innocence has been corrupted. He is no longer just an average boy with a father, but instead has fled to a new country with a fugitive and been abandoned by his father, although he will grow up to believe his father has died in the hurricane. This final scene reflects the ultimate result of Dexter’s efforts to balance being a father and a serial killer.

Harrison’s importance in the show lies in how the color is used around his character to reflect his father’s past and present attempts to be a father figured. At times, the colors were foreshadowing of the end of the show, and other times it seemed to suggest that perhaps Dexter and Harrison could live happily in peace. However, ultimately, the color choices in the show reflect that Dexter fails at compartmentalizing his paternal duties and his dark urges, resulting in the innocence he sought to keep in his son being ruined. The creators of Dexter invested time to develop this importance of color choice and using it to enhance the experience and struggle of Dexter as he interacts with his son.

Tiger: Man’s Best Friend, Still the Wolf’s Descendant

Sentimentality focuses on the relationship humans develop with each other and with their keepsakes and trinkets, while the sublime emphasizes the temporary nature of relationships and that everything inevitably leads to solitude or death. In Edgar Allan Poe’s novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, the protagonist’s strongest relationship is with his dog, Tiger, who is snuck onto the ship to join in the adventure. Tiger is a sweet, loving dog that obviously reciprocates the love and affection that Pym expresses, but his attachment to Pym is less compelling than his wild nature when their situation grows grim. Poe twists the sentimental into the sublime, exposing that they are not mutually exclusive using Tiger as a demonstration that a loving, supportive relationship can be demolished and turned into something to be feared.

Tiger, as is the case with all dogs, is a multifaceted creature, capable of numerous talents, emotions, and traits. The most evident trait of this newfoundland is his astounding capability of love for Arthur Gordon Pym. The attachment between the two is clearly demonstrated in the way that Tiger behaves around Pym. He is a sweet dog that shows affection and his excitement at seeing his owner when he first enters the crate to join Pym in his adventure. “[W]ith a long and low whine, he commenced licking my face and hands with the greatest eagerness, and with the most extravagant demonstrations of affection and joy!” (Poe 28). Tiger, who in this scene is unidentified by the narrator, is filled with love and affection for Pym and pounces on him to share this affection by giving him kisses. As the narrator describes it, Tiger is overwhelming in his positive response, “with the most extravagant demonstrations” thus expressing that the dog is an expressive and loving creature. This bond between the two can be inferred as mutual and both participants share a devotion towards each other.

Pym also directly describes his companion as “my faithful follower and friend” confessing the close nature of their relationship and further characterizing him as a reliable, caring dog, even going so far as to call him a friend rather than a pet. Tiger has earned Pym’s respect and love by being more than just a pet, a testament to how much more he is than an animal. He is “faithful” and a “friend” to Pym, implying that Tiger has done more than simply brighten Pym’s life as most animals do. Instead, he is on the same level as other humans, if not greater as later implied by Pym in the narration. When Pym feels hopeless, Tiger jumps into action to comfort him. “As I sank, utterly exhausted, upon the mattress, Tiger threw himself at full length by my side, and seemed as if desirous, by his caresses, of consoling me in my troubles, and urging me to bear them with fortitude” (Poe 33). Pym humanizes Tiger, applying emotions and motives to him that can be assumed to be true based on his actions. By attempting to comfort him and by seeming aware of Pym’s emotional state, Tiger is not only portrayed as a caring companion that seeks to make Pym feel better, but also an intuitive and intelligent creature.

Newfoundlands are rather intelligent dogs and Tiger seems to carry that trait as well, as shown in his interactions with Pym. Not only is he emotionally intuitive, but Tiger proves his intelligence by helping carry a note to Pym for Augustus. However, since Pym experiences momentary lapses in judgement and tears apart the note, he relies on Tiger to retrieve the pieces later. “To my astonishment (for I had taught him none of the usual tricks for which his breed are famous), he seemed to enter at once into my meaning, and, rummaging about for a few moments, soon found another considerable portion” (Poe 38). Despite being untrained to do this task, Tiger is intelligent enough to understand what Pym wants and carries out the task well. Without Tiger, Pym would have descended into madness sooner and Augustus would never have been able to share the news of the mutiny or convey the seriousness of the situation to Pym. He serves an important role in the plot of the novel in the first chapters, but the relationship between Tiger and Pym serves Poe’s underlying message in the novel to a greater extent.

Tiger’s relationship with Pym is the prime example of sentimentalism in the novel. Pym confesses that he loves his dog more than anyone else in his life. He even refers to his dog as his friend, implying a mutual respect rather than an “owner/ pet” dynamic that one would expect. “Most people love their dogs—but for Tiger I had an affection far more ardent than common” (Poe 29). Their bond is one that transcends the traditional, commonplace love that people feel for their pets. This closeness is expressed by both parties. Since Tiger’s thoughts cannot be conveyed through the narration, instead they are interpreted by the audience through his behavior towards Pym. As shown before, Tiger seems to be exuberant about seeing Pym again, but also intuitively aware of Pym’s distress later. Their relationship is built on an emotional connection between the two. “I had rescued him, when a puppy…and the grown dog repaid the obligation, about three years afterward, by saving me from the bludgeon of a street-robber” (Poe 29). Tiger owed his life to Pym and vice versa, making the bond between the two one that the reader almost envies. Poe develops this beautiful relationship between man and dog that transcends what one typically would expect by characterizing this dog as loving and heroic and in tune with the narrator’s emotional turmoil. This is the sentimental, the warmth and security that Pym feels because of Tiger’s presence in the crate with him. However, this pure relationship becomes strained, leading into the sublime moments of the text.

The loving relationship between Tiger and Pym takes a sour turn when Tiger seems to revert to a savage state due to the lack of food and water available for the two of them. The sublime plays into this turning moment as Pym describes the terror of being alone with Tiger and no longer feeling the safety and comfort that previously was a component of their relationship. “[Tiger’s] eyeballs flashing fiercely through the gloom…I could distinctly perceive his eyes fastened upon me with an expression of the most deadly animosity,” (Poe 41). The imagery of this scene reflects the tenet of the sublime of few, haunting details. There’s little description of Tiger, but he is focused on his eyes “flashing fiercely through the gloom” that fills the reader with dread. The previously regarded as sweet dog is suddenly a threat in an already dire situation, elevating the tension. This turn of Tiger’s personality marks the turn of their relationship and the shift from sentimentalism to sublime. Poe uses this change to demonstrate the sublime that can suddenly arise and force one to face their mortality. As opposed to the sentimental that produced feelings of belonging and love, this scene creates tension between the companions and throws Pym into solitude as he cannot rely on Tiger in this state. Instead of the love of sentimentality, instead there is the “most deadly animosity” in his friend. “[T]he dog sprang with a loud growl towards my throat…I felt the sharp teeth pressing vigorously upon the woolen which enveloped my neck” (Poe 42). Poe then uses this scene to show that Tiger has taken up a savage disposition, completely disregarding his previous affection and acting out of his established character. Instead he behaves more like the vicious predator that is his ancestor, the wolf. Pym recognizes this difference and does not call him by his name, but rather refers to Tiger as “the dog” which reflects another change in their relationship, as earlier he had been quick to call Tiger his “friend” rather than an animal. Poe uses Tiger to show the drastic shift that can occur in relationships and the terrifying realization that close loved ones can turn, leaving one in solitude or facing their or mortality.

The sublime and the sentimental seem as though they are opposites, but in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket Poe sets out to expose that they are intertwined. By establishing a character as sweet and loving with a close relationship to the protagonist, he sets up the sentimental, but uses dire situations and poor luck to show that these relationships that people heavily rely on can easily be twisted into threatening interactions. Tiger’s behavior shifts drastically to show that the sentimental relationships can be unreliable and thus be sublime at the same time because people, and animals, can suddenly change their attitudes, ruin and desert relationships, leaving others in solitude or fearing for their lives, as is the case in this novel. Thus, there is an overlap between the sentimental and the sublime that Edgar Allan Poe exposes through the close companionship between Arthur Gordon Pym and Tiger.

The Victim of Prejudice: Hays Has Something to Says

Mary Hays’ The Victim of Prejudice follows the story of a well educated girl who is slowly exposed to the gender bias of society and brought to ruin. Hays stresses the importance of education in the novel by having this protagonist so well-taught by Mr. Raymond. However, Hays means to show that despite this education, women will always endure systematic abuse. Mary is raised in a utopia when she lives alone with Mr. Raymond. Once the boys, William and Edmund, are introduced, the bias of society begins to creep into her world and academic education cannot prepare her for the injustice that follows. Men and the patriarchal society that Hays reflects in her novel are responsible for the downfall of women and keep them submissive through this cycle of abuse where women like Mary are educated but their education does not improve their status or allow them social mobility. Thus, The Victim of Prejudice is a novel exposing that men cause the downfall of women while also providing them with education to give them false hope before crushing their spirits.

The novel opens with Mary introducing herself and the setting of the novel. She narrates that they lived in Monmouthshire, described in a footnote as “pleasingly diversified. A portion is mountainous and rocky, but the rich land in the valleys and hills is full of woods and pastures” (Hays 179). The footnote sheds light on the area where she spent most of her time. This rural county likely meant she was far from the more populated cities and lived a more secluded life in her early childhood. Thus, Mary Hays has picked a setting that one can imagine is a utopia, far removed from society and gender bias, a microcosm for the development of Mary. In her narration, Mary talks only of her education with Mr. Raymond who has retired to this secluded life. Her education is seemingly rigorous. “I was early inured to habits of hardiness; to suffer, without shrinking; to endure fatigue and occasional labour” (Hays 5). Hays is attempting to establish that Mary’s education was thorough before the action of the novel begins. From this initial introduction, the audience might assume she is a fortified young girl and that Mr. Raymond was preparing her for life outside of their microcosm. Her narration implies that she believed herself to be taught “to suffer…to endure” but as later events show, this statement becomes ironic. Mr. Raymond attempts to teach her how to endure hardships but instead fails her by keeping her in the microcosm so she is unaware of societal expectations, class structures, and gender bias. He then introduces the next men to fail her and push her closer to ruin.

Mary’s bubble of safety in the rural community is punctured by the introduction of William and Edmund, boys meant to become “men of the world.” Their introduction leads to Mary’s first disobedience in chapter III when she steals grapes from Sir Peter Osbourne, but more importantly, she falls ill after the incident, which cannot be interpreted as a coincidence. This moment comes after Mr. Raymond reprimands her and she is diagnosed with scarlet fever (Hays 17). She takes the fall and suffers the consequences after William challenges her, introducing the first time her microcosm is disturbed and she is unjustly punished for her sex. “Trespassing on Sir Peter’s vineyard to disprove William’s assertion … Mary is forced to confront the disharmony between her conception of unimpeachable right and a distinctly gendered antagonism to it” (Zunac 3). Hays uses this scene to explicitly show the disconnect between how Mary was raised alone and when the boys, representative of the outside world, are brought into her bubble. Whereas until the boys are brought in, she believes herself capable of suffering and enduring, now she pushed towards a new suffering both mental and physical. The scarlet fever is a metaphorical punishment and a tool to suppress Mary in her attempts to prove herself. Based on the biblical nature of the event, one can even assume this scarlet fever is comparable to the punishment Adam and Eve received after eating the forbidden fruit. This proves that Mary’s safe bubble is punctured by the introduction of the boys and her first encounter with gender bias is through William, leading to her first punishment.

The characterization of William also shows how Mary is first negatively influenced by a man. Mary is a thoughtful character that opposes the idea to steal the grapes. However, “the disposition of William was somewhat impetuous, impatient of control, and liable to sudden gusts of passion” (Hays 11). Although William doesn’t commit the crime, he is the irresponsible one of the two and his temperament goes unpunished in the novel. Her behavior is influenced by his “impatient” and impulsive demeanor. While this is the first incident shown between the two, one can infer by this characterization that typically William should be the one disciplined; however, nowhere in this scene nor in another of the book is William the one disciplined or suffering for his actions. Instead, Mary suffers both a reprimand from Mr. Raymond, and as mentioned, some divine intervention gives her scarlet fever.

The incident with the grapes also introduces another character that further rips apart Mary’s microcosm and ultimately the main character to bring about her ruin. Sir Peter Osborne catches her stealing the grapes and his reaction demonstrates another gender bias that Mary is unaccustomed to. “Saying which, [Sir Peter Osborne] seized me, and, clasping me in his arms, kissed me with an odious violence” (Hays 22). In this particular scene, Sir Peter makes his first assault on Mary and the language she uses marks how Hays wants the audience to view him as an aggressor. A kiss is gentle, but Sir Peter “seized” Mary, implying a brashness of a man taking something. Hays directly parallels a “kiss” which should have affectionate connotations, with “odious violence” instead. Mary’s microcosm then is exposed to the violence of men through this scene, and in turn, makes the point that Hays aims to prove that men impose violence on women. “Moreover, the brute strength exercised by Sir Peter stands in for traditional conceptions of gender as the linchpin of domestic tranquility and, by extension, civil order” (Zunac 3). Men use violence and strength against women that have been domesticated and taught gentler manners to keep them in line. Mary struggles because she is still under the impression that education makes her equal to men like William or Sir Peter Osborne, and she is still only beginning to see the gender bias and expectations. In a patriarchal society that places importance on class, Sir Peter Osborne can aggressively take Mary with no consequences against him. In this instance, he doesn’t suffer any consequences other than William beating him off, although it seems that even this is miniscule. However, this begins the violation of Mary that the “domestic tranquility” and “civil order” expected at the time requires in order to keep women, especially those of lower class, submissive.

In this patriarchal society that Hays is reflecting in her novel, men control everything, even a woman’s own sexual awakening. Mr. Raymond, despite being the most progressive man in the novel, still is part of the system that controls women and forces them into roles. In chapter VI, Mr. Raymond tells Mary, “You are now, my dear Mary, approaching towards womanhood” (Hays 30). At first glance, this initially seems as though Mr. Raymond is making a general comment about Mary growing up, reaching adulthood. However, whether his intentions were pure and unbiased, later Mary confesses to William how this statement, and the following conversation, affected her perspective. “I knew not… that the regard I felt for you differed, in any respect, from our mutual and infantine fondness, till Mr. Raymond awakened my fears, and alarmed my tenderness” (Hays 53). In this way, it can be understood that Hays wants the audience to assume that Mr. Raymond forced Mary to address her sexuality before she was ready, inserting her in a position against her will. Women are not only sexually assaulted by men, but controlled in every aspect of their sexuality, implicitly or not as Hays shows through Mr. Raymond and Mary. This discovery also leads to Mary learning the hardships of class bias.

Mr. Raymond’s decision to retire to Monmouthshire with Mary and raise her seems to imply that he had intentions of sheltering her from city life and the prejudices of society. However, after introducing William and Edmund into her life, Mr. Raymond must tell Mary that she cannot be with William romantically, finally exposing her to the class biases she would suffer. He acknowledges that societal expectations and rules separate them, “Were it not for certain perspectives, I should perceive your growing tenderness with delight” (Hays 31). Mary is confused by his statements, but ultimately for several reasons. As mentioned, Mary was unaware of her feelings for him and as such, she cannot possibly be devastated by this discovery but is confused about this new information. More importantly, it is this introduction to the class and wealth bias that confuses her and the concept of William being a “man of the world.” This sudden exposure to another type of suffering she would endure confuses Mary. “What Hays demonstrates is the contradiction between social practices and reason which suggested that she and William were compatible” (Ty 4). Whether Mary saw William as a romantic partner or not in this scene, she did love him as a childhood companion and Mr. Raymond abruptly informs her that she cannot be with him, forcing her feelings into romantic ones and then taking hope from her. As Ty points out in their article, here is a moment when Hays is definitively destroying the microcosm that was created by education and seclusion. In their home, Mary knows things that make sense and are rational. Through this, Hays points out the ridiculousness of these “social practices” by putting it in the perspective of an educated woman that is unaccustomed to the biases that exist.

In the confusion of learning these social restrictions, Mary’s search for explanation leads Mr. Raymond to share the story of her mother, which is foreshadowing of Mary’s demise and exemplifies how the education given to women only serves to make them aware of their abuse. Using this tale, Hays also displays how women are deceived into believing that education and knowledge of the bias can lead to a different outcome. “The mother’s narrative is that of the seduced maiden, and… [reveals] that, following the codes of society, the mother’s standards of right and wrong behaviour are based, not surprisingly, on sexual purity” (Ty 3). Mary’s mother is the victim of a man deceiving her and leaving her destitute. After that violent violation, she is depicted as a whore in the novel, fallen from grace in Mr. Raymond’s eyes as he doesn’t recognize her. The importance here is that the mother falls to ruin so forceful because of “the codes of society” and not by choice. Her choices and behaviors are focused on the guilt of being impure because of societal expectations. She is shaped by the cycle of oppression. A man rapes a woman, leaves her, and she takes the blame. Mary’s mother sees this cycle of guilt and shame and asks Mr. Raymond to take her daughter and educate her. “[C]ultivate her reason, make her feel her nature’s worth, strengthen her faculties, inure her to suffer hardship, rouse her to independence, inspire her with fortitude, with energy, with self-respect, and teach her to contemn the tyranny that would impose fetters of sex upon her mind” (Hays 69). Such language is reminiscent of how Mary introduces herself in the beginning of the novel, when her microcosm is undisturbed. Mary’s mother is aware of how ill prepared she was for the world and asks Mr. Raymond to break the cycle by educating her daughter and preparing her for “hardship” and particularly important, “independence.” The implication here seems to be that independence will help Mary avoid the same seduced maiden tale that her mother fell victim to in her youth. Hays takes this scene to present to the readers the concept that perhaps daughters can be educated to break the cycle of oppression and gender bias. However, it becomes clear that Mary would still fall to ruin much like her mother did.

Sir Peter Osborne serves and the main antagonist in the plot of the novel. He continuously harasses Mary and assaults her to assert his dominance and claim her. Hays uses him to represent the patriarchal society that violates women. In a literal sense, he completely ruins Mary when he rapes her because of the importance society places on virginity. “[H]is native impetuosity, heightened by recent scenes of riot and festivity, by surprise, by pride, combined to effect my ruin” (Hays 117). How he is portrayed in this scene is important because it harkens back to how William was described as a child. Both men are described as brash, in this case his is “native impetuosity” where Hays claims that Sir Peter Osborne’s impulsiveness is an innate characteristic, one that he was perhaps born with. William’s characterization in the same way implies that all men of power or higher standing are impulsive and brash. Neither character is punished, which shows that society rewards these men rather than punishing them for their behavior. Hays also demonstrates that while women are typically the ones shown to be swayed by men and emotions, here it is Sir Peter that is “heightened by recent scenes of riot” which also once again carries the connotation of violence. Everything Sir Peter Osborne does is tainted with vices and violence, further demonstrating that the patriarchy that he represents is so rampant with these traits and uses them against women as Osborne does to Mary. “The rape was not a single act of violence but the culmination of systemic abuses and injustices that men in positions of power were culturally encouraged to act out against women” (Ty 5). Osborne is raised and taught by example to uphold this system and to abuse women, especially Mary who comes from a lower, illegitimate family. As Ty points out and as articulated in this essay, Mary is exposed to many injustices beyond the rape. Her fall has been building since the boys were introduced to her life and she became aware of gender biases, from there she is pulled into the system of abuse and brought to ruin.

An educated protagonist that falls to ruin and loses her potential effectively demonstrates the point that Hays aims for. In a patriarchal society, education cannot save a woman but instead gives her the tools to understand prejudice. In the perfect, rural world she lives in, Mary succeeds. However, the introduction of William and Edmund opens her world up to the truth of society’s biases against women. Men like William, Sir Peter Osborne, and even Mr. Raymond, violate and force women into ruin. Each man that interacts with Mary has served to push her towards ruin, even implicitly. Through The Victim of Prejudice, Mary Hays reflects the harmful cycle of oppression and biases that women are forced to endure, making it all the more powerful with scenes that give women hope like the peaceful microcosm of Monmouthshire and the hope that education will provide them social mobility and success.

Works Cited

Ty, Eleanor. “The Imprisoned Female Body in Mary Hays’s The Victim of Prejudice.” Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, edited by Lynn M. Zott, vol. 114, Gale, 2003. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.lehigh.edu/apps/doc/H1420045681/LitRC?u=lehigh_main&sid=LitRC&xid=579d9443. Accessed 27 Apr. 2020. Originally published in Women, Revolution, and the Novels of the 1790s, edited by Linda Lang-Peralta, Michigan State University Press, 1999, pp. 133-153.

Zunac, Mark J. “‘The dear-bought lessons of experience’: Mary Hays’s The victim of prejudice and the empiricist revision of Burke’s reflections.” Papers on Language & Literature, vol. 48, no. 1, 2012, p. 70+. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.lehigh.edu/apps/doc/A282955924/LitRC?u=lehigh_main&sid=LitRC&xid=e306f77d. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

Religion in Slavery: A Tool to Instill Passivity

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicts several characters as religious figures and the protagonist Uncle Tom is one of those figure heads. He not only becomes a Christlike figure, but he takes on the role of preacher at the plantations he works on, spreading the word of the bible. Historical evidence shows that religion did play a role in keeping African Americans submissive to white slave owners and that it was used as such. A newspaper article likely written from the white perspective shows that religious education was a responsibility of the slave owner and would serve to make slaves better, encouraging the perspective that religion would keep the African Americans passive in their roles. Another article that seems to be written by an unnamed author, but likely black writer suggests the same passive nature towards abolition. It reflects on the desire for freedom but suggests that it will only occur when God wills it as such.

Stowe does not directly claim that slaves were kept passive by teaching them about the word of God, but Uncle Tom’s presence and preaching does show that slaves taught the word of the bible were kept passive with the hope of finding freedom in heaven. Stowe accurately depicts that many slave owners did find it to be their responsibility to educate their slaves and this was a widespread mindset. “No rational mind can doubt that the effect [of educating slaves] must be equally favorable to the interests of the master, as to those of his now ignorant and degraded bondman” (Mere). This newspaper article poses religious education as a tool to be used and presents it as mutually beneficial for both parties. One can assume that the writer, who early in the article uses the phrase, “We have letters before us from Virginia” is written by a white author based on the authority they take by using “we” and continuing to discuss the religious education of the slaves. However, it still uses language that implies this religious education serves better for the masters than the slaves, stroking the egos of white slave owners. The description of the slaves is negative with words like “ignorant and degraded” suggesting that slave owners were being kind and benevolent by educating the slaves on their plantation. Thus, by using language that further separates the slaves from the white plantation owners, it paints the slave owners as kind and applies the twisted paternal concept of slavery to the situation, making it the responsibility of owners to educate the slaves and raise them from their “degraded” position in life, while still keeping them submissive through the promise of freedom in the afterlife for living religiously and passively and never acting out of violence or disrespect.

Similarly, another source from Colored American demonstrates that even free colored people felt that abolition was only capable through God, once again demonstrating that the religion that whites imposed on African Americans led to a passive acceptance of oppression. While the article suggests that they believe God will not stand for slavery to continue, the overarching argument is that God’s will is the only thing that will change the system of slavery. “We have no right to wish for the abolition of slavery, nor hope for the elevation of the free population of our brethren, if it be contrary to will and purposes of God” (Colored American). Based on the publication title and the unified language of “our brethren,” it is safe to assume that this writer is colored as well and likely free. This newspaper article also demonstrates the same passivity that Stowe implicitly writes into her novel, that many African Americans act as Uncle Tom and do not rebel against the system of slavery in the name of religion. This concept seems to be a pattern of thought, that God wills it so and as such the white men have a responsibility to education blacks and blacks have a responsibility to respect the world as God created it, thus instilling this passive acceptance of slavery in many people. While abolitionists existed that actively fought against slavery, Stowe seems to accurately also capture that religion played a role in keeping slaves passive in the system of slavery.

Historical sources show that on the parts of whites and blacks, religion was used to keep slavery intact. Whites felt that part of their role was to educate the slaves in religion, presenting to them the word of God and as such also instilling the idea that heaven will provide them with the freedom they desire and the salvation that keeps them at peace. This teaching then inspires the freed slaves to also pursue this path of peace and acceptance of slavery because it is taught to them that it is God’s will. Thus, while active abolitionists existed at the time, Harriet Beecher Stowe accurately presented the truth that many slaves were kept passive in slavery like Uncle Tom by the use of slavery to instill just enough hope into the slaves to keep them from revolting.

Works Cited

Mere. Journal. “Instruction of the Slaves.” New-York Spectator [New York, New York] 5 Aug.

1833: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 24 Oct. 2019.

“Religion.” Colored American, 16 Dec. 1837,

https://libraries.udmercy.edu/find/special_collections/digital/baa/item.php?record_id=120

0&collectionCode=baa.