This week, the poet C.L. White wrote on Facebook that "the pandemic has sort of smeared puzzle glue on all our circumstances and made those of us that are planners and seekers and doers into awkward statues." I have felt for weeks as if I've been trying to move through rapidly solidifying tar, caught in what will soon be stone. I had not thought, though, that it might be me–and not the world around me–that is calcifying. I like this turn, this idea of myself becoming more and more permanent as life has stilled, rather than working against some permanence around me.

And the statues I see around Bethlehem, all this public art without public gaze, appear somehow more animate in the slow. Sculptures around town seem weirdly expectant, unsure what happened with life-as-it-was, as they suddenly find they’re the only ones around. Whatever their faces held before, their expressions now appear anxious and wanting.

In the courtyard by City Hall and the Northside public library branch, statues of children playing ring-around-the-rosy have scarves tied across their noses and mouths. Their gazes each reach past one another, over the shoulder and beyond their hand-clasped circle. Worried, even at play.

In the courtyard by City Hall and the Northside public library branch, statues of children playing ring-around-the-rosy have scarves tied across their noses and mouths. Their gazes each reach past one another, over the shoulder and beyond their hand-clasped circle. Worried, even at play.

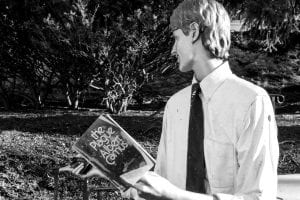

A sculpture of a student on Lehigh University’s campus holds a book, the sleeve for Albert Camus’ The Plague slipped over its stone binding. The student, whose duct taped facemask has fallen off and blown away, is smiling, laughing, his head turned away from the open book in his hand. How can he not look away from the plague, though? Not laugh?

I wonder how many different people have been dressing up the statues. These gestures, or pranks, seem to reflect some desire that art keep moving and changing even when our lives cannot. Even art as constant as sculpture for, as Benjamin writes, “that for the Greeks, whose art depended on the production of eternal values, the pinnacle of all the arts was the form least capable of improvement–namely sculpture, whose products are literally all of a piece." People, unlike sculptures, are not all of a piece, though. They’re assemblages, hopes and loves and impulses all pieced unneatly together. So if sculpture is the art of endurance and timelessness, its geologic material symbolic of the eternal, how can we find ourselves, who are so precarious, in this art?

When I find a statue wearing a face mask and blue gloves, I think this may be how. I think that emphatic unchanging-ness in art is not what we need now that our lives feel so unchanging. While sculpture’s eternal resonances may steady us during the chaos of ordinary life, now that life is so very slow and unordinary, we ought not look to eternity. Attaching medical supplies and ironic book-sleeves to sculptures draws these 'eternal' works into the realm of revision, and assemblage–where we are–rendering sculpture something more akin to film. That is, playing dress-up with statues is a kind of "radical renunciation of eternal value." And if we’re feeling ourselves turn to stone in this quarantine, it will take a radical renunciation to pull us out from the cooling tar.

You must be logged in to post a comment.