Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat: A Fresh Take on an Ancient Story

By Sam Layding

Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat is a 1972 musical with music written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Music by Tim Rice, performed on Broadway for the first time in 1982 (Wikipedia). The show is based on the Biblical stories of Jacob’s son Joseph in Canaan, the namesake multicolored coat that Jacob gave him, his betrayal by his brothers, and his rise from being a slave to the Pharaoh’s Vizier in Egypt (Genesis 37-47).

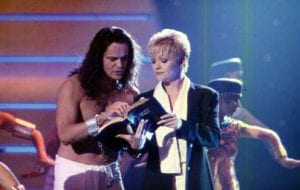

The show was made into a movie in 1999 which stars Donny Osmond in the lead role as Joseph. Here’s a clip of two of the opening numbers from the film version, “Jacob and Sons” and “Joseph’s Coat”:

The pair of songs introduces Jacob’s family and establishes Jacob’s favoritism of Joseph, which leads to the somewhat tenuous relationship between Joseph and his brothers and their plot to sell him into slavery in Egypt later in Act I. Joseph is eventually reunited with them in Act II when famine brings them to Egypt to seek food, forcing them to unknowingly beg Joseph for food after he has become the second most powerful man in Egypt. Joseph decides to spend some time playing with their emotions before revealing himself to his brothers, forgiving them for their betrayal: “I shall now take them all for a ride; after all, they have tried fratricide” (Joseph, “The Brothers Come to Egypt”).

The story, shared by the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, and the Islamic Qur’an, is one that is fairly well-known in Western culture, if only for this show alone; in Eric Ziolkowski’s review of Loving Yusuf: Conceptual Travels from Present to Past by Mieke Bal, he writes that “today, of Americans familiar with the episode of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, more are likely to know it from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s hit musical Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat than directly from Genesis” (Ziolkowski 625).

The way in which the show brings a deeply religious story to the stage through musical theater in a way that is accessible to an incredibly wide audience is noted in the book Playing God: The Bible on the Broadway Stage by Henry Bial, who observes how Rice’s strategy of “restating the biblical narrative in contemporary vernacular language… [lends itself to] humor and self-awareness” (Bial 180). Self-awareness through the breaking of the fourth wall by the narrator and references to contemporary culture, to name a few examples, leads to a show which is entertaining but does compromise on the religious solemnity of the story. Bial previously mentions in his book that “In its joyous communal affect, Joseph… can occasionally envelop the audience in a moment of transcendence, but they are unlikely to experience such a moment as spiritual” (Bial 170). This lack of spiritual awareness of the show’s content is a consequence of making it more accessible to a broad range of viewers, with an assumed precedent that God is watching over the characters without explicitly making references to God nearly as often as happens in the original story.

There are a few examples of this self-awareness throughout the show. First, the narrator clearly interacts with the audience and seems to understand that she is part of a play. In the opening number, “Prologue,” the narrator addresses the audience, saying “If by chance you are here for the night, then all I need is an hour or two to tell the tale of a dreamer like you” (Joseph, “Prologue”). In the first musical number with the whole company, our narrator opens with a clearly tongue-in-cheek setting: “Way, way back, many centuries ago, not long after the Bible began” (Joseph, “Jacob and Sons”). In a later song, “Go Go Go Joseph,” she admits her knowledge of the show’s future events by singing “we’ve read the book, and you come out on top,” an obvious allusion to this being a story from a literal sacred text (Joseph, “Go Go Go Joseph”).

Toward the end of Act I in the musical number “Potiphar,” we learn the story of how Joseph, now a slave and the leader of the household of a rich Egyptian man named Potiphar, is seduced by his master’s wife and subsequently jailed. During the song, the narrator reminds us in an aside that, despite the audience’s disbelief that these events really happened, “It’s all there in chapter thirty-nine of Genesis” (Joseph, “Potiphar”). In his book, The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible, Jonathan Kirsch writes how “a modern storyteller… makes [these forgotten stories] accessible to a readership that’s forgotten what’s in the Bible… [Webber] feels obliged to reassure us that he did not just make up the half-comical, half-erotic tale” (Kirsch 10).

In Act II, the character of the Pharaoh in several songs is a clear caricature of Elvis Presley, singing and dressing in a style very similar to the King of Rock & Roll. This can be interpreted as a stark contrast between the culture of Egypt and that of Joseph and his kin from Canaan, and more broadly as a clash between popular culture (Pharaoh’s eccentric style) and religion (Joseph and his brothers’ more conservative dress). Not unintentionally, Joseph’s character is able to bridge this cultural gap in the same way that a modern art form like the Broadway musical is able to bring an old religious story to an audience that may not necessarily subscribe to any of the beliefs expressed by the show.

Focusing on the adaptation of a traditional story using a diverse mix of modern music genres allowed Joseph to be incredibly successful and stand the test of time as a religious musical; in the book Andrew Lloyd Webber, author John Snelson tells us how “the way the work adapted pop culture… to a religious tale and with such a fresh sound was innovative. It was not a big stage musical, it was a direct piece of pop” (Snelson 61). By going through significant changes in its musical style in its early development, the show’s “rooting in a pop basis has enabled Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat to remain continually relevant” (Snelson 64). This show has proven to be a reliable staple of Western theater in the forty-six years since its premiere and delivers its classic Jewish story in a manner that appeals to almost any audience due to its family-friendly nature and fantastic mix of musical styles. Joseph helped establish the genre of religious Broadway shows including Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell, both of which use similar techniques of adapting a traditional Biblical story through a modern lens and retelling.

References

Henry Bial, Playing God: The Bible on the Broadway Stage

Jonathan Kirsch, The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible.

Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

John Snelson, Andrew Lloyd Webber

Eric Ziolkowski, Reviewed Work: Loving Yusuf: Conceptual Travels from Present to Past by Mieke Bal

Wikipedia, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat