Kelly Austin is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Lehigh. She is in Bududa, Uganda this summer with a group of students pursuing her research in community health. You can read her previous post here.

Overall, things have been going well the past few days. Power has returned! Yay! Hopefully it will last several days without interruption. On Saturday morning, Mark & I took the students to go see one of the favorite weekend activities in Bududa – bullfighting ! Bullfighting is not like we think of it in the US, with a red-clothed matador beckoning a bull, but rather, large bulls fighting each other until one of them runs off, concedes, or is badly injured. It is essentially chaos, with hundreds of people (mostly men and children) on a large pitch (soccer field) running around, yelling, following whichever bulls are in action. The crowd scatters for their lives whenever a bull gets tired of fighting or concedes a contest, taking out whoever is in his way. Luckily, we saw no human injuries, and Peter and Dezz Zaale kept our Mzungu group safe at the top of an embankment behind some very thorny bushes. At one point, the bullfighting settled a bit, so they brought out a female bull to rile the fighting male bulls up. Boy did that work!

! Bullfighting is not like we think of it in the US, with a red-clothed matador beckoning a bull, but rather, large bulls fighting each other until one of them runs off, concedes, or is badly injured. It is essentially chaos, with hundreds of people (mostly men and children) on a large pitch (soccer field) running around, yelling, following whichever bulls are in action. The crowd scatters for their lives whenever a bull gets tired of fighting or concedes a contest, taking out whoever is in his way. Luckily, we saw no human injuries, and Peter and Dezz Zaale kept our Mzungu group safe at the top of an embankment behind some very thorny bushes. At one point, the bullfighting settled a bit, so they brought out a female bull to rile the fighting male bulls up. Boy did that work!

The tone changed that afternoon when several of the Zaale grandchildren and members of our Lehigh team started to fall ill with fever and vomiting. I spent most of Saturday afternoon dolling out ibuprofen and Cipro (medication for bacterial infection), taking temperatures, and making my students ramen noodles. In total, 3 of 6 the Lehigh students were ill. They all started to improve slightly on Sunday, but 2 of them continued to have fevers at night. This is a common sign of malaria. I contacted my good friend, Dr. James Wafula, and he agreed that I should take all of those with fever to his clinic (which is one the other side of the Bududa loop) on Monday morning for malaria testing.

I took one group to the clinic right at 9am – 2 of the students with persisting fever and one of the Zaale grandchildren that was obviously much sicker than her sister. When we arrived at the clinic (driving in 4-wheel drive for 35 minutes, on a “road” that has gone  from horrible to worse with the rain) to find well over 150 people waiting in line. The clinics are always especially crowded on Mondays after the weekend. The day prior, Maayi (mother) Elizabeth Zaale had gone ahead and starting treating her very ill grandchild with Coartem (malaria medication) before we were able to take her to a clinic for the malaria test. I really try to encourage the locals not to do that, as giving medicines before getting a test can lead to a host a problems, including antibiotic resistance (this is in fact an area that I am researching currently). However she remarked, “You can die waiting in line at the clinic for a test.” Her point hit home as I saw the crowd of people waiting. I know from the work I do here that many of them walked miles to get there, likely leaving their homes before it was even light out. They’ve already been waiting for hours, and will wait for hours more. Malaria can kill an infant in as little as 18 hours after first showing symptoms.

from horrible to worse with the rain) to find well over 150 people waiting in line. The clinics are always especially crowded on Mondays after the weekend. The day prior, Maayi (mother) Elizabeth Zaale had gone ahead and starting treating her very ill grandchild with Coartem (malaria medication) before we were able to take her to a clinic for the malaria test. I really try to encourage the locals not to do that, as giving medicines before getting a test can lead to a host a problems, including antibiotic resistance (this is in fact an area that I am researching currently). However she remarked, “You can die waiting in line at the clinic for a test.” Her point hit home as I saw the crowd of people waiting. I know from the work I do here that many of them walked miles to get there, likely leaving their homes before it was even light out. They’ve already been waiting for hours, and will wait for hours more. Malaria can kill an infant in as little as 18 hours after first showing symptoms.

I have extremely mixed feelings as we approach the crowd and Dr. James pops out from his examination room. He waves us in and we jump all the others in line. We skip the usual 6-station procedure (check in, vitals, examination, lab testing, consultation, pharmacy) and directly get patient numbers then proceed to the lab. I feel horrible skipping all the local people, but I know that I also need to put these emotions aside and prioritize my students’ health and well-being. It’s my job to keep them safe here.

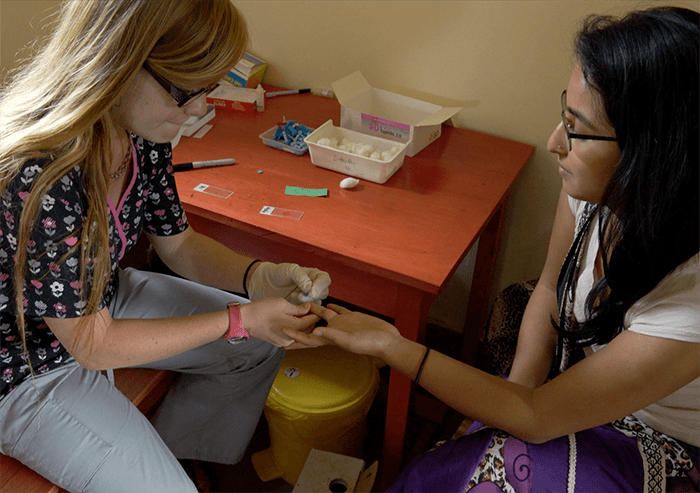

I hold the 2 and half year old baby while the lab tech pricks her ring finger on her left hand and puts a drop of blood on the slide. She bellows and cries (and glares at me for the rest of the day, as if to say – you did this to me!). Emma carefully examines each of the slides using a microscope, looking for the telling, tiny rings on the red blood cells that are indicative of the malaria parasite. All 3 of them (the two Lehigh students and the Zaale grandchild) have “mps +”, malaria parasites, plus one. The severity of malaria is rated on a one-plus to four-plus scale, with one plus being the mildest. They all likely have only one plus due to the preventative anti-malaria medications we are all taking, and the Coartem the baby was given on Sunday. While the anti-malaria medication can help to prevent malaria, it is not full-proof, as you can see.

Maayi Zaale was suffering from malaria the week prior. Malaria is a unique disease with a combination vector between humans and mosquitoes. An infected mosquito must bite a human, then 9-14 days later when the human shows symptoms, a mosquito can bite the infected human again and carry it to another human. Clearly, there are mosquitoes in the compound now carrying the parasites, and the longer one goes without treatment, the more possibilities there are for the mosquitoes to spread it to others. While we all sleep under bed nets, it is impossible to keep them off you all of the time, as we are often eating, helping to cook, and doing work in the mornings and evenings outside when the insects are most active.

The students and grandchild are given the proper dosage and instructions for taking Coartem, and we insist on paying the 2,000 UGX fee (~60 cents) each for the medications from the clinic, despite the pharmacist, Michael, saying that we don’t need to pay as we are friends of the clinic. We set off back to the Zaale compound, and I quickly get the students settled, then grab the other Lehigh student who also had a slight fever on Saturday (but since then had said that she felt fine) and the second grandchild and drive them back to Bushika to the clinic. We jump the line with even more impressively this time, being ushered directly into the lab, where they simply write our names on the slides. As I am holding the 4 year-old grandchild to get her prick, the foreign volunteer lab worker says, “We might as well test you also,” and I too donate a drop of my blood to a clean slide. The Lehigh student and myself are negative, but the second grandchild also has “mps +” and after a quick trip to see Michael in the pharmacy, we are on our way once again.

By the time we get back to the compound, it is 2:30pm. I had to call Dezz several times to keep pushing the interviews I had scheduled for the day back. Luckily, I was still able to get 3 interviews in during the afternoon. I will absurdly admit that I feel a strange twinge of jealously. I have been studying malaria here for 4 years, but have not yet had the disease myself. Don’t worry – I’m not about to stop taking my preventative anti-malarial or forfeit sleeping under a bed net. I’ve seen too much hardship from this disease to ever wish it upon anyone, including myself. I’m happy to report that the students and grandchildren are already feeling much better. Less than one day later and everybody is back at work this morning. We will take extra precautions over the next 2 weeks, wearing deet or bug spray religiously, and lowering our nets even if we are just reading or working in our beds in the afternoons. While malaria can be treated effectively if you catch it early, get a proper test, and take the medicines accordingly – if you don’t, it quickly becomes a life-threatening illness. Mosquitoes kill more each year than any other animal or insect (including humans) on earth. It is a disease that has been with us for centuries. It knows how to adapt and survive.