Elizabeth Dolan is an Associate Professor of English at Lehigh University. This summer she embarked on a research trip to the British Library.

From the outside, archival research doesn’t look like much: one scholar alone, reading old and oddly sized books and manuscripts hour after hour. But these crumbling documents hold stories that come alive in the scholar’s mind and offer insight into the nuances of human experience over time. One arrives at an archive with a research plan, an intention to answer a well-defined question. But, once the scholar is elbow deep in the sources, the archive itself begins to shape the research—offering up in the midst of hours of tedious reading unexpected finds, opportunities for new lines of inquiry. These surprises, the questions they raise, the mystery, the putting together of pieces are the great pleasure of archival work.

Thanks to a Faculty Innovation Grant, I’m on the first of several trips in AY 2016-17 to various archives, this time to the British Library in London. I last conducted research in this venerable institution in 1995, while still in graduate school. At that time, the collection was held at the British Museum. One walked up the grand marble steps, past the large marble lions, and into the darkly paneled library to unearth old texts. The new British Library, situated several blocks away from the British Museum, opened in 1998. It exudes a beauty and light appropriate for this invaluable collection of 150 million items, including manuscripts, maps, newspapers, magazines, prints, drawings, musical scores, patents, sound recordings, stamps, and, of course, books. As the web site explains, “If you see 5 items each day, it would take you over 80,000 years to see the whole of the collection.” And it grows by 3 million items a year.I’m working in the Africa and Asia Collection, tracking down three brothers whose careers took them to India in the early nineteenth century: William Towers Smith and Nicholas Hankey Smith worked for the East India Company, and Lionel Smith served in the Army

large marble lions, and into the darkly paneled library to unearth old texts. The new British Library, situated several blocks away from the British Museum, opened in 1998. It exudes a beauty and light appropriate for this invaluable collection of 150 million items, including manuscripts, maps, newspapers, magazines, prints, drawings, musical scores, patents, sound recordings, stamps, and, of course, books. As the web site explains, “If you see 5 items each day, it would take you over 80,000 years to see the whole of the collection.” And it grows by 3 million items a year.I’m working in the Africa and Asia Collection, tracking down three brothers whose careers took them to India in the early nineteenth century: William Towers Smith and Nicholas Hankey Smith worked for the East India Company, and Lionel Smith served in the Army

and was stationed in India. I’ve studied their mother, the poet, novelist, and children’s author, Charlotte Smith (1749-1806). Her fall into poverty from her gentry class upbringing, evident in her frequent moves from house to house in the last 20 years of her life, meant that she couldn’t send her sons to Oxford or Cambridge to obtain the degree necessary for them to take up the life of a clergyman that she imagined for them. Instead they had to look beyond England to make a living, and collectively served in Nova Scotia, the West Indies, India, and Persia, building the British Empire.

and was stationed in India. I’ve studied their mother, the poet, novelist, and children’s author, Charlotte Smith (1749-1806). Her fall into poverty from her gentry class upbringing, evident in her frequent moves from house to house in the last 20 years of her life, meant that she couldn’t send her sons to Oxford or Cambridge to obtain the degree necessary for them to take up the life of a clergyman that she imagined for them. Instead they had to look beyond England to make a living, and collectively served in Nova Scotia, the West Indies, India, and Persia, building the British Empire.

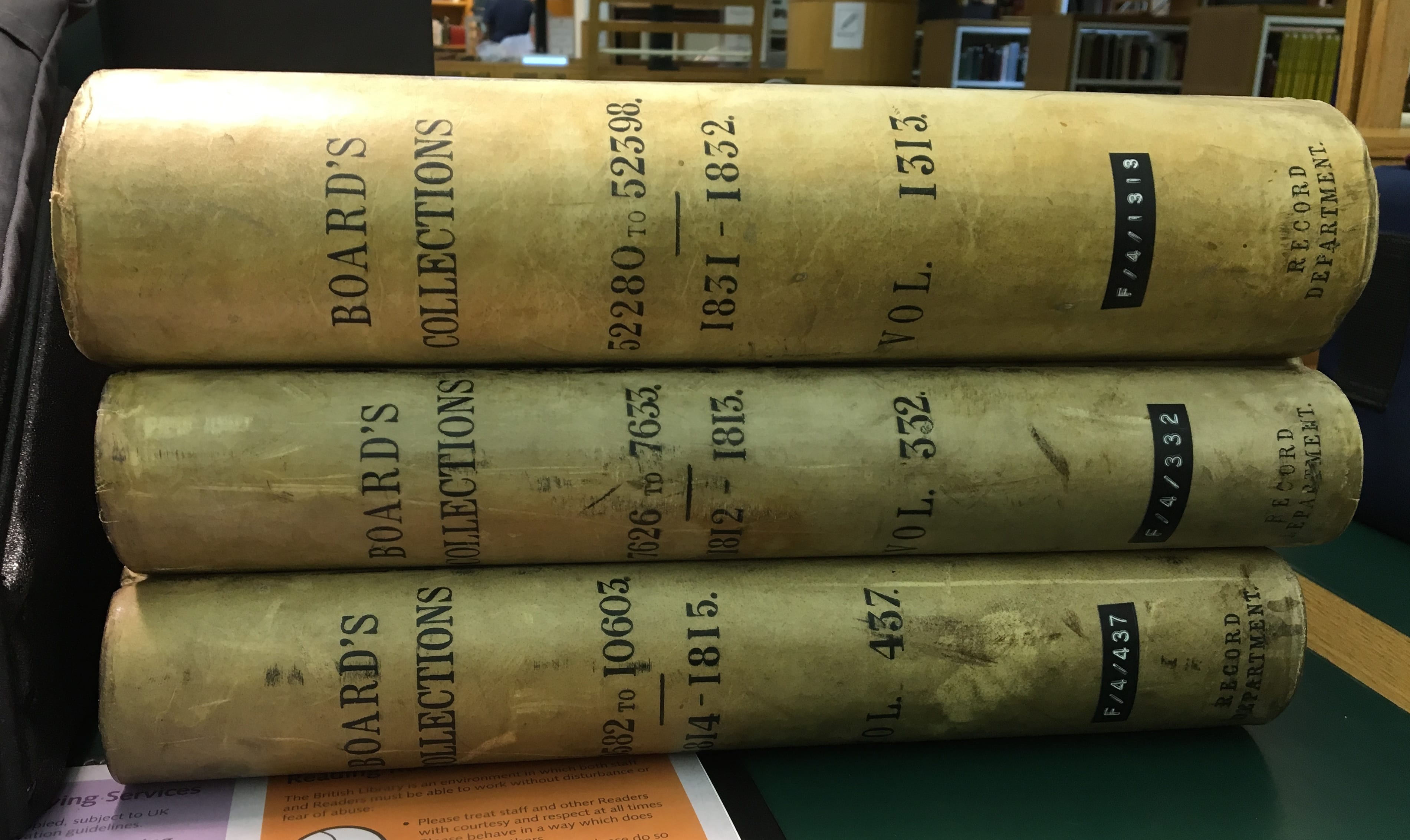

Arriving at the library on the first day, I had to show three forms of id and a research plan to the registration office in order to obtain a Reader’s Pass. This done, I proceeded to the Africa and Asia Reading Room (pictured above) where the sources I’d ordered ahead were waiting. I began with Lionel Smith, since I’ve already traced the end of his career; he served as Governor of Barbados and Jamaica during Emancipation (1833-39). I found 48  sources in the catalogue and ordered 10 to begin with. I started with three bound volumes of official handwritten correspondence to and from the Directors of the East India Company from 1812-1833.

sources in the catalogue and ordered 10 to begin with. I started with three bound volumes of official handwritten correspondence to and from the Directors of the East India Company from 1812-1833.

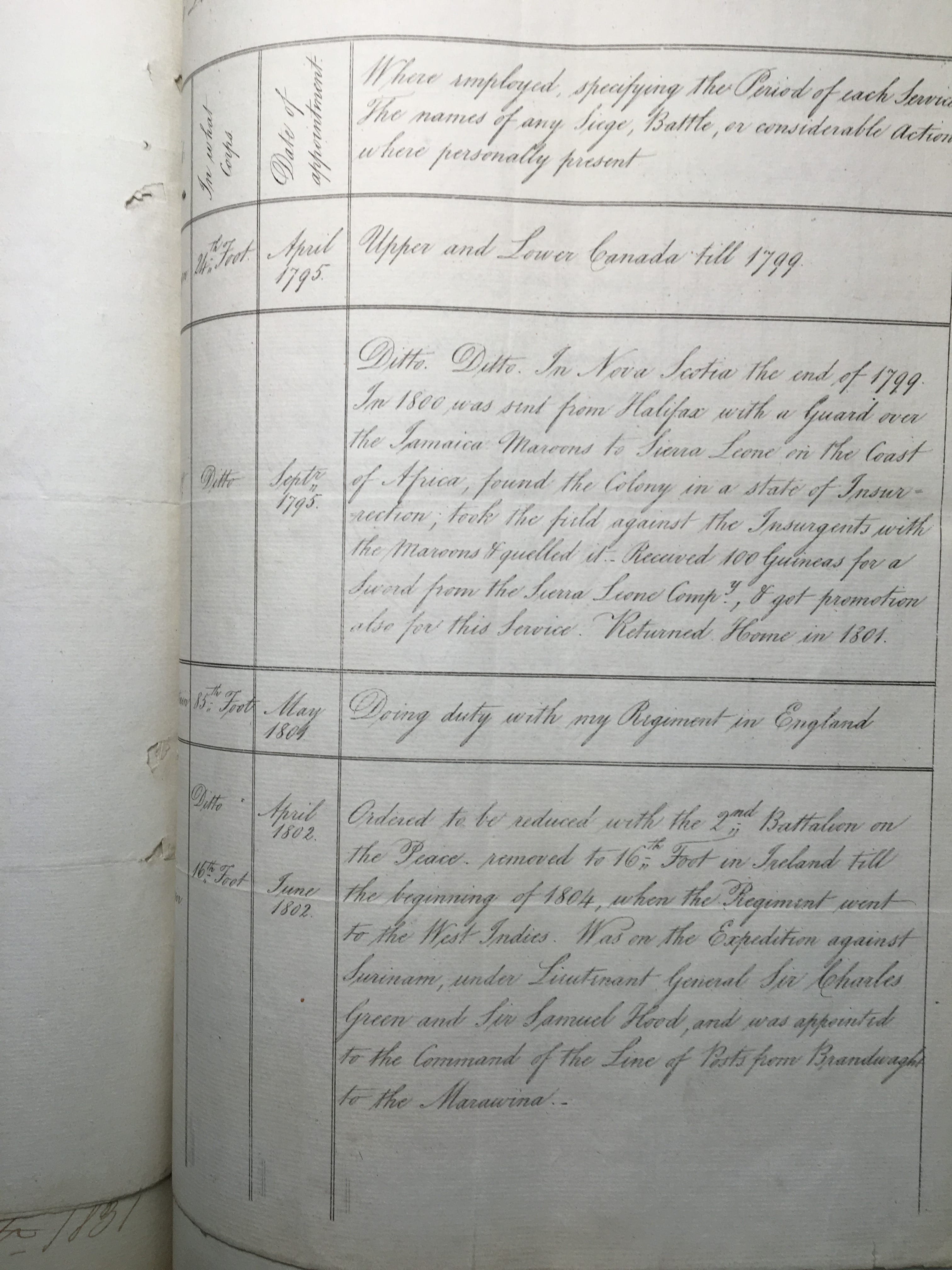

After a fruitless, 2-hour search through he first volume, the second volume proved a treasure trove for my purposes. Leaving India in 1831, after 22 years uninterrupted service, then Major General Sir Lionel Smith applied to the East India Company for funds to retire. His appeal includes a chart he compiled of his complete service in India, an incredibly convenient summary that I had not even imagined I would find.

The information is crucial to reconstructing Lionel Smith’s life and career, and the chart  itself saved me days of sifting through the archives to piece together the highpoints of his service in India. While I’m grateful for the unexpected short cut he provided, the real pleasure in this find is reading Sir Lionel’s own words and hearing moments of resonance with his mother’s writing.

itself saved me days of sifting through the archives to piece together the highpoints of his service in India. While I’m grateful for the unexpected short cut he provided, the real pleasure in this find is reading Sir Lionel’s own words and hearing moments of resonance with his mother’s writing.

Charlotte Smith struggled to support her 12 children by publishing books and poetry and by writing letters to the trustees of her father-in-law’s estate to appeal for financial help. Her letters repeatedly reference her tireless efforts to support her family, and her own ill health (scholars think she suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and ultimately died from uterine cancer). In his letter to the East India Company Board of Directors, Lionel Smith, speaking of himself as a “memorialist” asserts:

“Your Memorialist has had no advantages beyond his Pay and allowances, and having a family to bring up, is about to retire with very slender means. . . . Your Memorialist therefore most respectfully solicits your consideration towards his long Services, to enable him to support his Rank, and few remaining years, in comfortable retirement, rendered more necessary by the state of his Health, seriously impaired as that has been, by a long and uninterrupted residence in a warm climate.” (Smith to the Chairman and the Court of Directors of the East India Company. 19 October 1830. British Library: IOR F/4/1313/52348, emphasis mine)

It’s this human aspect of these historical documents, and in this case the echo of affect across a generation, that brings me to the archive and keeps me in my seat hour after hour. I’m fascinated to see that Sir Lionel tried retire in 1830. It doesn’t seem that he was successful as he was appointed Governor of Barbados in 1833 at age 56, Governor of Jamaica in 1836, and Governor of Mauritius in 1839, dying in 1842, while still working—an unfortunate circumstance he shares with his mother. Part of the mystery I have yet to solve is why he was not able to retire as he wished.

successful as he was appointed Governor of Barbados in 1833 at age 56, Governor of Jamaica in 1836, and Governor of Mauritius in 1839, dying in 1842, while still working—an unfortunate circumstance he shares with his mother. Part of the mystery I have yet to solve is why he was not able to retire as he wished.

The research I’m conducting will inform my book project on empire and family, and an article on Lionel Smith’s service in Barbados. Books and articles are typical and desirable research outcomes for a humanities scholar. This trip I’m also meeting with a descendant of Lionel Smith, Sir Eldred Smith-Gordon, to share my research with him. This opportunity to share information with someone about his ancestor, while not necessarily valuable for my career, is rewarding and joyful to me personally.