- This event has passed.

Mark Wonsidler: SCULPTURE

August 20, 2008 - September 28, 2008

RECEPTION: Friday September 26, 6-8pm

A Conversation between

Sculptors Nancy Shaver and Mark Wonsidler, July 2008

NS: Patina seems so important to you as an element. I’ll ask you why?

MW: For me, patina is the accumulation of known and unknown history in the surface of an object. What’s known are the marks on the surface and the way they reveal how the object was made or used. The rest—intention, circumstance, biography—is lost. That contradiction of gorgeous presence and intractable silence holds my attention. These surfaces are like abstract paintings, but the painter is anonymous.

NS: Can you say more about how you relate to the idea of ̒anonymous̉ ?

MW: It has to do with my sense of authorship: the question of how much I need to do, or how loudly. In found objects the author may be multiple, unknown or the weather. My own actions can’t always be discerned from the existing condition of those objects. I often make alterations that play with imitating the found, accurately or inaccurately.

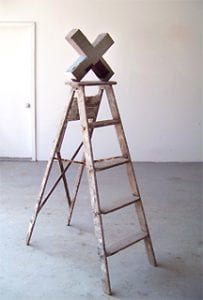

NS: It seems to me that when you build up your own patina as you did in this blue chair, that you are making the object itself more abstract than, for example, the ladder which you haven’t touched, which has its own patina due to age and use. Do you like playing those two things against each other?

MW: Yes, definitely. The core relationship at work is between what I find and how I change it. Sometimes my interventions are awkward impositions, such as building up a new surface on this blue chair.

NS: I like this direction. It’s not doing a lot with the found object, but in a way it is. By creating your own patina on this old object, the combination of new and old creates a new object. Did you find it that way?

MW: No, it was a chair that I cut down. Its structure is based on a step-stool that I saw in a shop. My obsession with seeing the lopsidedness of a chair-turned-into-a-stool was the impetus, and then the slant evolved as I was cutting it down.

NS: In other pieces you create a patina of age in a new object, for example the piece I included in History, Use and Borrowed Landscape. That particular patina has a very faux feel to me. I’m assuming that you liked how that evoked décor in the most exaggerated way, is that true?

MW: I’m more interested in décor as it relates to theatrical furnishings—as set, prop or ornament—but I do have a longstanding fascination and horror about the manufacture of fake antiques for home decorating. It’s an area that I sometimes point at through my work, usually through exaggeration.

NS: In the end of that exaggeration, you made this banister look a bit like a fern unfurling. Did you know that would happen, or did it happen in the process?

MW: I think the association of that curling shape—as shepherd’s crook, musical instrument or frond—was in the back of my mind.

NS: Subliminally important?

MW: Yes. I worked on the piece horizontally while I was building the surface, then I started taking it out of the studio and moving it around. Upending it provided a moment of recognition. From that recognition, the idea of leaning developed.

NS: How much of that sort of observation and then recognition is something that happens as you work? How much of it exists before you begin? Because you know—that’s a chair, that’s a stool, that’s a ladder…

MW: Most of it happens while I work. What I find is some way to shift or offset whatever it was that I started with. The set of starter objects is not that varied. Sometimes I think I could collect buckets forever. But the solution to whatever I’m making remains in the background until I see it, until some accumulation or juxtaposition triggers a new awareness. That becomes the rightness of the piece.

…

NS: You’re interested in the painter Giorgio Morandi, and some of your work refers to him. Why do you like him?

MW: I think it’s the ordinariness of the objects involved, and the limits that he’s working with in terms of props, and compressed space. The range of possibilities that emerge from the slow careful rearranging of those elements feels endless. Also the moments of intense color are very surprising. Lately, I’ve been looking at the way his surfaces overtake the objects, mash them together or make them abstract. I’ve been trying to find ways to use painting differently in my work.

I know you are interested in him as well. What attracts you to him?

NS: I think for me, Morandi is a painter who is unashamedly involved in the sensuality of paint, and where that makes an object and where it makes space. And then within this usually very limited range of color he defines very solid objects that are incredibly strong and appealing. His choices feel based in a philosophy of life—in the sense that these limitations are not necessarily limitations. Looking and looking and looking again is a whole different experience.

MW: There’s so much pleasure in that repeated looking, and patience.

NS: The willingness not to do very much.

…

NS: What about trompe-l’oeil in terms of your work?

MW: Well, it’s related to the faux, certainly. I made a piece a few years ago that was a collection of old black-and-white enamel basins and new buckets painted to match. I like that a surface can be misleading, particularly when the magnetism of completeness or sameness breaks down upon inspection. So that’s one notion of trompe-l’oeil.

I’m interested in how trompe-l’oeil painting could create a fictional inroad to a closed surface, a box for example, where fiction acts as a counterpoint to the reality of the found object. That’s one of the things I like about this blue chair. It has moved from being a found object to being like a drawn or painted shape. In a way I’m reversing trompe-l’oeil—making real objects seem artificial or like pictures.

…

MW: When we met at Bard College in 1997, you suggested that we shared the same sensibility. I wonder how you would describe that?

NS: I think it’s a sensibility of the ordinary having a lot to say, seeing objects as sculpture, and seeing simple gestures like wrapping as sculptural actions. That, and the importance of the history and integrity of an object. The object may not be used for what it was intended but it’s given the respect of another position, a visual position, after its long hard use as a practical object.

…

NS: I know from your earlier work that you’re an incredible craftsman and have a great deal of patience and ability to make something really refined. It seems like you have given that up, I’ll ask you why?

MW: I haven’t given it up, but my attention has shifted. Those earlier works were really hand-scale and often involved the dense accumulation of many layers and materials. They had an internal proportion which was absorptive—you can go into them in some way because they’re smaller than you, but at the same time you also encompass them. One of my fundamental questions was about how small articulations could address more space. It began with dispersing and arranging the objects throughout a room. Then I began to consider larger objects, like furniture. So in that process, I felt I also needed to relieve the density of all that layered activity by spreading it out. I became curious about the weight of a single isolated gesture, a more strategic intervention. For example, shifting a thing so that it would lean in one direction, adjusting an object in a less obvious way.

NS: But why wouldn’t you make a more crafted object?

MW: It’s not an anti-craft stance. It has something to do with patina and the way we were talking about the element of anonymity in the found object. As my decisions became more subtle, more imitative of the existing logic of the objects, I wanted my own hand making to be less distracting and more in tune with the unknown actions made by the person or persons who had it before I did, in whatever logic they made those actions. So, working roughly, broadly—like the way you paint a barn—became useful to me as a kind of hand, and that overtook the idea of more meticulous craftsmanship.

NS: I wonder if you’re thinking about picking that up again, that older vision?

MW: In the past year I have become a lot more interested in those practices that I left behind, like drawing or painting. I’m curious to see what happens. The hand-scale works and the larger sculptures are really two forms of the same obsession—in the sense that obsession can manifest as both manic, accumulated action and as attenuated staring with slow, precise, perfecting adjustment. The idea of having both in the work is compelling.

PODCAST: Mark Wonsidler: Fall 2008