Living an Impact-Focused Life

By Noah Weaver

What’s your Why?

I believe I was put on this earth to:

Leave a long-lasting, positive impact on humanity.

My purpose is to:

Heal those in need, including (but not limited to): medical and emotional needs of the disadvantaged under-resourced.

I believe (my core values):

Are integrity, respect, fairness, empathy, and service to others.

The one thing I must do before I die is:

Know that I positively impacted the world in such a way that inspires others to do the same, and “pass the baton” on to the next generation of public servants.

My advocates and supporters all believe I:

Have unequivocal integrity and passion for bettering the lives of others through my work.

The evil I want to eradicate in this world is:

Public misinformation campaigns designed to distract us from what matters and the lack of empathy that is “justified” by such misinformation campaigns.

I want to work in order to:

Live a comfortable life and simultaneously sustain my life’s higher purpose.

Walk the Talk – Your How

If you are truly committed to your Why, you show it in your everyday behavior. It is all air until you do it. Working from your Why, How do you prove that you are true to your Why in all you do?

I always:

Give my best effort in anything and everything that I do.

I never:

Do anything without a greater purpose or loss of integrity (even if it’s to my own detriment).

My work style is:

Focused, efficient, and communicative.

I try to treat people:

With fairness: I generally give people the benefit of the doubt, but I also remember that the door swings two ways.

I approach problems by:

Thinking of why something occurred and attempting to understand the nature of the problem first. From there, I work to find solutions that satisfy all parties to the greatest extent possible.

Victories are time to:

Celebrate your accomplishments and enjoy yourself, but also to give credit to those who have earned it as well.

If another attacks my point of view I:

Try to understand their perspective and meet them halfway (if possible).

If I fundamentally do not agree with what an organization or person is doing, I will:

Go out of my way to avoid working with that organization or supporting any aspect of their business.

Your Credibility – Your Whats

You have just spent some considerable time at Lehigh, and specifically in the Global Social Impact Fellowship, on many whats. Your whats include lab research, formal presentations, writing research papers, engaging with people in other cultural contexts, building prototypes, designing and building systems, raising funds, hiring employees, etc. The whats you have collected along the way are critical to your credibility when you are entering the workforce or applying to the best graduate and professional schools. They signify a credible currency to which organizations can assign value. Create a list of your Whats that are truly reflective of your Why & How. You did these things because you believe (Why) and you acquired them in the following (How) manner. These are examples you can use in interviews.

| What Have I Done |

List of Experiences, Accomplishments, and Lessons Learned |

| Degrees, Minors, Certificates, Fellowships |

Degrees: A.S. in Biological Science, B.S. in Molecular Biology (2023)

Fellowships: GSIF, MTSE

Certificates: Basic Life Support (BLS), Social & Behavioral Research, Human Research for Biomedical Researchers, Good Clinical Practice, Protecting Research Participants, Leadership, Critical Thinking and Problem Solving (Competency), |

| Research Experiences

|

Biomedical Research Internship at St. Luke’s, GSIF

|

| Inventions and Innovations

|

Ukweli data collection and analysis |

| (Social) Entrepreneurial Ventures

|

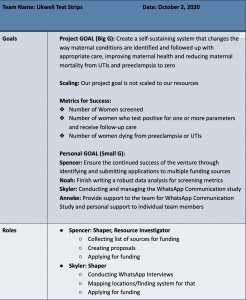

Ukweli Test Strips

|

| Publications

(Formal and Informal)

|

Data-Centric Operations Design for Disseminating a Biomedical Screening Technology: A Case Study.

A Systematic Review of WhatsApp Application Trends in Healthcare.

POC Screening, Diagnostics and Health Outcomes in Low-Middle-Income Countries: A Case Study of Ukweli Test Strips.

An Analysis of Community Health Workers’ Use of a WhatsApp Communication Network.

|

| Formal Presentations

(at Lehigh and Beyond)

|

GSIF mid-semester presentation (Spring 2020 and Fall 2020)

GSIF final presentation (Spring 2020 and Fall 2020)

GHTC (October 2020)

|

| Awards and

External Recognition

|

Paige L’ Hommedieu Scholarship, Stabler Scholarship, NCC Student Senate Scholarship (x2), Louis Moore Pine Scholarship (x2), NCC Foundation Scholarship, Joseph P. Liberati Memorial Scholarship, GELH Grant,

|

Articulating and learning from GSIF-related Experiences. For each of these prompts, we want you to identify one and only one specific and compelling event/incident/experience/moment and identify exactly how you grew personally and professionally through that moment.

| Teamwork Experience

(and Lessons Learned)

|

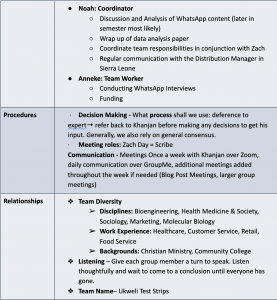

Equitably distributing workload- this must be discussed up front (e.g. during weekly group meeting). I grew from this by understanding how to set clear expectations among group members to avoid conflicts later. We specifically set team expectations at the beginning, middle, and end of each semester.

|

| Fieldwork Experience

(and Lessons Learned)

|

N/A |

| Conflict Resolution Experience

(and Lessons Learned) |

Our group and I discussed with Khanjan how we felt not all group members were giving the fellowship their best effort and the strain it was putting on some group members. We were able to have a tough conversation and reset expectations, and we now seem to be turning the corner a bit.

|

| Leadership Experience

(and Lessons Learned)

|

You have to offer the opportunity for group members to take ownership and accountability for their work. That means giving credit when credit is due, but also being honest when someone isn’t performing to expectation. Leadership is just as much about knowing when to step back and let the group lead itself and knowing when to intervene and take charge when necessary. An example of this would be when I established near-daily communication with our distribution manager when no one else took the initiative. I did not necessarily know if it was my place to do so, but I decided that someone needed to step up for the advancement of our project goals, and it ended up working out thus far. |

| Dealing with Chaos, Ambiguity, and Uncertainty (and Lessons Learned) |

Taking each challenge one step at a time is essential. Multiple times, I have had to discuss with our group members about taking each thread one step at a time to avoid causing a panic for us as individuals. By adopting the attitude of “we will do the best we can, and whatever happens is what happens” allows a lot of stress to be relieved and, paradoxically, greater efficiency to be achieved while working. A good example includes the irregular scheduling of our pre-WhatsApp study interviews. Our distribution manager usually only let us know the day before an interview was to be conducted, and this required careful coordination and balancing of everyone’s schedules in order to make the study work.

|

| Personally Challenging Experience (and Lessons Learned)

|

Recently, my family pet died. This pet helped me through some of the most challenging moments of my life. Unfortunately, I was also the one who had to make the tough decision to euthanize our family pet when others were too scared to make that decision (because it was the right thing to do: the pet went into multiple system organ failure).

I was unable to find motivation to do much course work for a couple days, but I was communicative with my professors about how I was feeling and they were surprisingly understanding. I have been able to mentally recover enough to continue working, and I also allow time for myself to grieve in a healthy way when necessary. I learned that it’s okay to acknowledge when I am feeling weak, and that people tend to be more understanding than they may seem on the surface.

|

| Cross-cultural Experience (and Lessons Learned)

|

Speaking with individuals in Sierra Leone requires extremely direct communication. For quite a while, I felt uncomfortable communicating with our Distribution Manager because of how unfamiliar I was with the cultural norms of SL. However, by relying on iterative feedback from Khanjan, my group members, and seeking advice from those whom I trust, I have been able to adapt to this challenge and appreciate the complexities of human interaction and cross-cultural interaction. I learned that I have to be comfortable with uncomfortable interactions for the betterment of the project (e.g. it’s sometimes uncomfortable for me to be too forceful with someone despite that being their style of communication).

|

| An experience that helped you connect your GSIF work to your discipline / major.

|

Hearing the stories from CHWs during our WhatsApp Communication Study pre-interviews and how our work effects (to a degree) the ability of mothers in Sierra Leone to receive treatment is meaningful to me. Remembering that I study molecular biology in order to understand human life and make it better is what allows me to connect the impact of the GSIF program to my major.

|

| A moment that boosted your sense of agency and self-efficacy – you felt like you can speak for yourself, get stuff done, take on the world and make it better.

|

I felt greater self-efficacy when I answered questions at GHTC and during our presentations. For quite a long time, it was difficult for me to overcome public speaking anxiety to the point that I couldn’t form original thoughts in front of large groups of people. Now, I feel I have been able to conquer one of my biggest fears and as if I can do anything I set my mind to. |

| A moment where you felt like you truly have a strong sense of purpose and belonging in this dynamic, globalized interdependent world.

|

I felt a greater sense of belonging when I realized that I had a specific set of skills that my group members do not also possess (just as they, too, possess skills that I do not have). The ability for me to uniquely contribute to the Ukweli project in a meaningful way made me feel a stronger sense of purpose and a sense of belonging. |