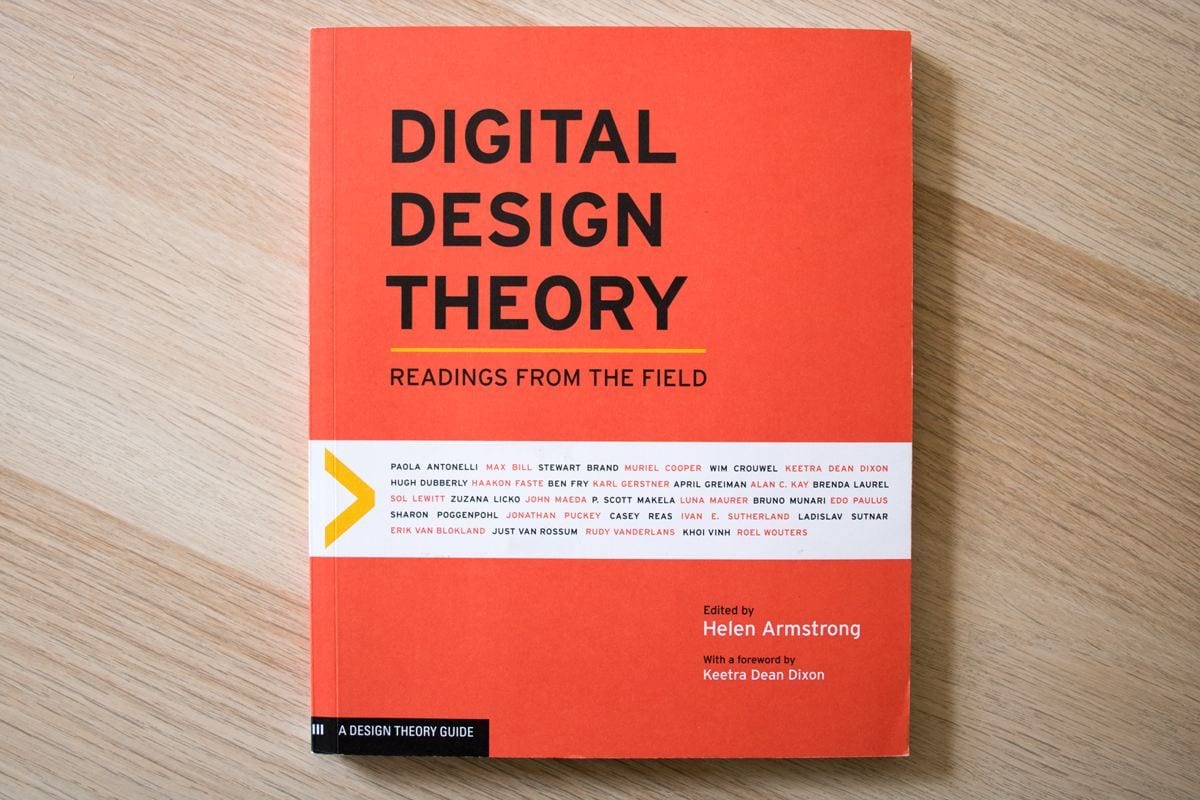

In her most recent book, North Carolina State University Associate Professor of Graphic Design Helen Armstrong follows the trajectory of computational influence on graphic design. She assembles a collection of thirty-two reprinted essays written by an array of influencers from social engineering, art and design, curatorial practice, computer programming, and computer science.

The essays are chronologically arranged in three sections. The first, “Structuring the Digital,” surveys a seminal decade of the Cold War (1961-71) that produced computing technologies, and academic theories about computation. Essays by Ladislav Sutnar, Bruno Munari, and Ivan Sutherland recount how increased algorithmic methodology in the sciences opened the way for expanding quantities of data, prompting designers to develop aesthetics of efficiency. Designers employed Swiss-style typography and modular grids as universal form-making systems. An essay by Swiss designer Karl Gerstner describes a grid as “a proportional regulator,” (31); its programmatic nature allows the maximum quantity of constants with the greatest variability. Armstrong has included Gerstner’s writing in other collections, but it is also useful here because it provides the design community access to text from his out-of-print 1964 book, Designing Programmes.

review appeared in Design and Culture,9:3, 351-353, DOI: 10.1080/17547075.2017.1369737

The second section, titled “Resisting Central Processing,” is comprised of essays from the 1980s and ‘90s that tempered industry fears the computer would lead to professional redundancy. During these decades, technologies like the personal computer, laser printer, and the Internet, initiated new aesthetics and expanded the designer’s capabilities to include author and programmer. In her essay, former Visible Language editor Sharon Poggenpohl explains her effort to close the gap between, “design and the new visual computer technology” (58), while computer scientist Alan Kay’s advocates for designers to learn programming skills to enable a “grand collaboration” (81) with their computing tools. This section highlights contributions by design practitioners and educators who were early adopters of computation.

Some readers may object to the fact that Armstrong has relegated several key authors to just a few pages. Designer and technologist John Meada is limited to an excerpt—the only single-page entry among the compiled essays. Designer April Greiman’s essay is the shortest text in the book, though Armstrong enhances it with a two-page reproduction of Greiman’s 1986 design for Design Quarterly, which doubles as visual essay. By limiting the footprint of more established authors in the second section, Armstrong devotes space to look back on texts by authors who have passed on—Murial Cooper (d. 1994) and P. Scott Makela (d. 1999). Alternatively, it allows participation in the book by contemporary and emerging scholars.

The third section, “Encoding the Future,” reflects on the present state of graphic design and anticipates its future. Armstrong’s selections show how twenty-first century designers are using new technologies to push the limits of design for behavior, open systems, and sharing communities. Ben Fry and Casey Reas (former students of John Maeda) write about developing their open source program Processing, which allows visual thinkers to program their own computational tools so that they can bypass proprietary ones. Hugh Dubberly explores the paradigmatic shift in design ethos away from the “mechanical-object” of conventional design and towards the “organic-system” of sustainable design. Khoi Vinh observes how digital media continues to flatten disciplinary barriers and creates a trans-disciplinary work environment for designers operating in a new, creatively aware and innovative society. Finally, Haakon Faaste speculates on how this transition in graphic design might lead to a future with artificial intelligence in “Posthuman-Centered Design,” a new essay written for this volume.

Armstrong is not the first to publish a compendium of writings on graphic design. But Digital Design Theory: Readings from the Field is fundamentally different from most, including those currently in print from Allworth Press. Where those are topically broad, un-illustrated, and sourced from mainstream design media and design association journals, Armstrong’s is focused, richly illustrated, and sourced from academic journals, conference proceedings, and authored books. It is also deeply historical. By breaking down the volume into chronological eras, it becomes clear how thinkers influenced subsequent generations. For example, Wim Crouwel’s experimental New Alphabet (1967) anticipated digital fonts used on display screens, and later became an exemplar for some of the fonts created by Zuzana Licko and P. Scott Makela in the 1990s. Digital Design Theory is an ideal resource for educators and students who desire a theoretical history of computation in graphic design.

::::::