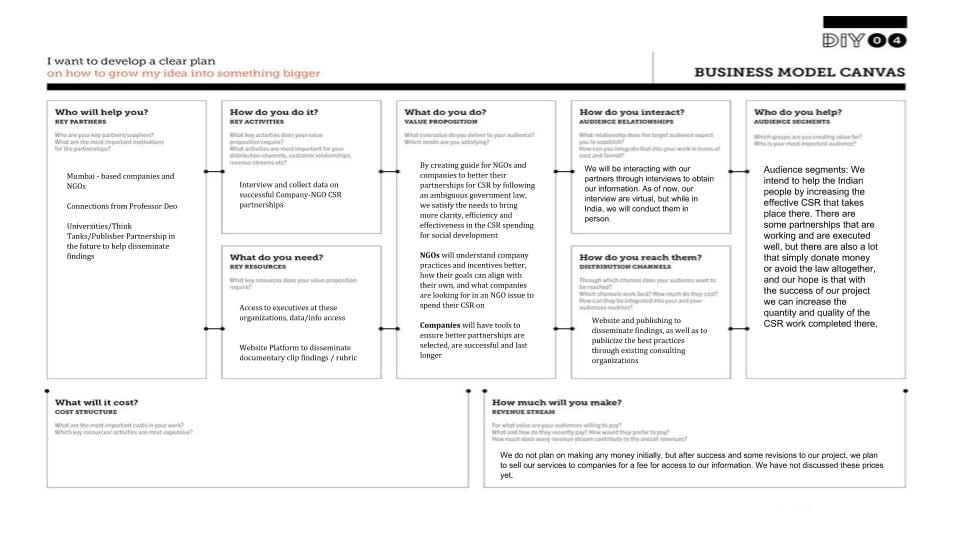

1. Identify two SPECIFIC funding sources for the design phase of your project and two SPECIFIC funding sources for the dissemination (implementation/distribution/

- For our design phase, we do not have much spending that needs funding prior to our actual dissemination. The main sources of funding we might need for creating the documentary clips logistical costs are minimal. But finding a sponsor from research organizations in India is a possibility to pursue, through partnerships we already are beginning to formulate.

- For our dissemination phase, we will need funding to a) get our documentary clips and rubric/report published on a legitimate platform to reach our targeted audience and b) in the future, organize our findings over time to create a validated source published for a wider range of companies. A potential funding source can be nonprofit organizations located in India that work as consulting to other nonprofits and organizations to better manage their own initiatives. The way this could work is if our project would work as an extension of these organizations, as a consulting organization in this specific field of study. As such, the details of this structure are vague right now.

- Another avenue for dissemination funding can be through research institutions and think tanks that undertake similar research to ours, but fail to address the specific research question and problem our project undertakes. We have found that the current literature addresses how NGOs view what companies are spending on for CSR as inefficient, but there are limited to no sources on the decision making processes for the companies themselves. Therefore, our project will take this unique approach which will be of interest to research institutions and think tanks to possibly fund for our dissemination.

- Another possibility for funding our dissemination is to charge a sort of fee to access our specific rubric and recommendations for companies. However, this seems as a stretched possibility at best, as our project would have to gain significant credibility in a short amount of time in order to legitimize it as valuable enough for companies to pay for access.

2. Identify five specific partnerships that you need to forge to advance your project forward with the ultimate goal of positively impacting atleast one million people. Describe exactly how that partnership might help you achieve scale and why that entity might be willing to work with you.

- Partnership with research institutions in India already involved with CSR study: As we got in touch with Ashoka University this semester, they shared key insights on the research they have conducted on the Ministry of Corporate Affairs database in terms of the value and volume of CSR expenditure, the geographical and thematic distribution of CSR and the percentage of corporates that complied with the mandatory 2% CSR expenditure. By gathering data-sights from this research, we are able to analyze with various different parameters the current trends in CSR research and base our own questions off of existing questions.

- Ashoka University got us in touch with organizations like Samhita and Sattva that have produced knowledge products on this topic in the past and continue to do so (They have shared access to their research materials here and here.) We plan to continue to reach out to organizations that have conducted research in this area to have a broader understanding of the shifting CSR field. Research institutions have a willingness, in the pursuit of knowledge dissemination, to work collaboratively with researchers like us. In a partnership with such organizations, we can offer our case-study approach as a insightful and unique way in making the impact for transitioning from analyzing CSR to making it better.

2. Similar to the last approach, getting in contacts with think tanks and forging partnerships with them will help us achieve scale by connecting us with their existing organizations and individuals that are in the CSR research field as well. A potential to reach out to is Corporate Responsibility Watch, a think-tank working in the CSR space has produced numerous knowledge products on CSR trends in India and has conducted some interesting qualitative research on the topic.

3. Long term partnerships with companies on the ground in India will be especially vital in order to make our project scale in the future. These companies will have resources that we will need in order to make our study valuable and usable for companies in the future. By allowing us to take a deep dive into individual CSR programs in these countries, companies will open themselves up to good publicity for showing how their CSR programs have been successful in making an impact. This will encourage many more companies to similarly partake in case-study research in collaboration with us, and allow us to expand our selection of company-organization partnerships.

4. Another partnership to pursue will be those with government entities that already deal with analyzing the effects of the Companies Act. We know the government has some dealings already with recording the current effects of the Act and involvement of companies with their spending, but taking a deeper dive into the formulations behind the law can help address whether the law is fulfilling its intended goals and reaching the measured levels of success that the government of India intended for it to do.

5. We can lastly forge vital partnerships with dissemination points for our research. This incorporates all of our previous partnerships as well as additional connections with blogs, websites and publications that we will reach out to that have an interest and stake in sharing our research with their current readership audience.