Creativity and Stress

Written by Quinn Klessel – Artwork by Connie Ulm – July 26, 2021

According to the American Psychology Association (2019), roughly 75% of Americans report that they experience physical, mental, and behavioral symptoms from an excess of stress. Biologically, stress can be defined as, “a condition that imposes severe demands on the physical and psychological defenses of the organism”(APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2021). The human body has a fine tuned way of dealing with situations that the individual deems to be stressful. The issue is that when we encounter too many incidents that we deem stressors, we overuse this stress response and our bodies experience negative side effects. Too much stress has the potential to lead to a decrease in productivity, but there are ways to counteract this. One way is through participating in creative arts, which has the ability to lower stress levels and increase both productivity and problem solving abilities. A stressed out person may respond to the advice of “Take a break, draw a picture” by saying, “That is a waste of my time.” However, one would find that this person would have a much less grumpy response after they took a break and drew a picture. Their stress would be lowered. Don’t believe me? At the end of this article, if you are experiencing some stress (no matter how much or how little), try your hand at the creative activity I shall put forth.

When a person identifies something as a stressor, the brain registers a distress signal that causes a fight, flight, or freeze response (Katz et al., 2021). The body releases a hormone called epinephrine during this response, and this hormone triggers a series of biological changes in our bodies that allow us to more efficiently deal with danger. If our brain continues to perceive danger for a prolonged period of time, it uses a chain reaction within a system called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) to release cortisol, a hormone into our system. This system to deal with stress works perfectly under most circumstances. However, if our brain reacts to situations in a way in which we perceive extreme danger where there is not, we can overuse this stress response and cause harm to our bodies from an excess of the secretion of glucocorticoids, such as cortisol (Chu et al., 2021). The negative side effects of excess stress include headache, chest pain, nausea, anxiety, restlessness, irritability, and depression (MayoClinic, 2021). These are all things that at the least have the potential to inconvenience an individual’s life.

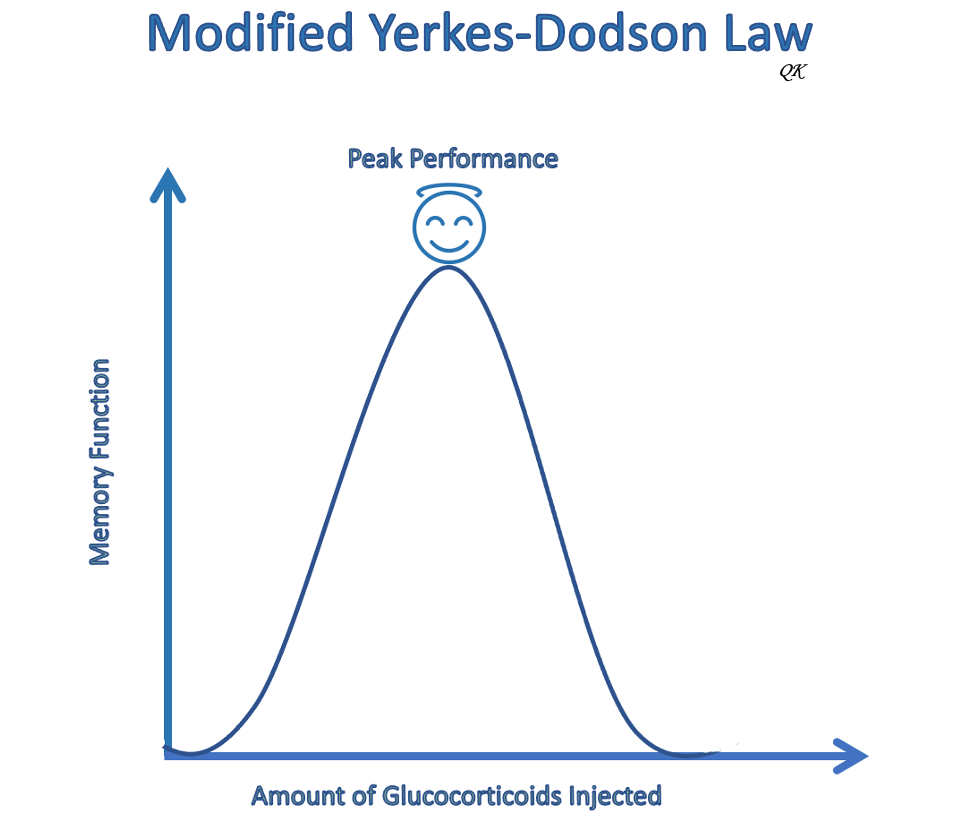

One might wonder at this point, is stress just entirely harmful? Should humans try to experience as little stress as possible as to avoid all risk of the negative biological effects of too much stress? While too much stress can be harmful to our bodies, too little stress is also not ideal. It was once thought that glucocorticoids, like cortisol, only inhibited brain functions. This would imply that stress only inhibited brain function. However, the Yerkes-Dodson law presents a different theory. This law showcases a graph containing an inverted-U shape with the x-axis being arousal and the y-axis being performance. According to this law, there is an optimal amount of stress needed for peak performance; too little or too much stress will not cause this best scenario.

Many studies have been conducted using the injection of glucocorticoids into mice and other organisms to see if the theory that stress hormones only inhibit cognitive function is true. While conducting these tests, it was discovered that there are two types of glucocorticoid receptors in the brain: Type 1 and Type 2. At a state of rest, glucocorticoids are mostly bonded to the Type 1 receptor. However, when more glucocorticoids are injected to the point where the Type 1 to Type 2 receptor bonding ratio is approximately equal, it is found that memory function is at its peak. Therefore, when the glucocorticoids have bonded to Type 2 receptors as much as they have bonded to Type 1 receptors, the mice show the best memory performance. This demonstrates the idea that an inverted-U graph with the x-axis representing the amount of glucocorticoids injected and the y-axis representing memory function is the ideal representation. Too little or too much of the glucocorticoids will not provide peak memory function, thus, too little or too much stress will not provide peak memory function (Lupien et al., 2007).

The conclusions that can be drawn from this experiment are that some stress is helpful to increase cognitive function, however too much stress may be detrimental. Now that we understand stress is not an entirely bad thing, we understand that we should not be making an effort to remove humans from stressful situations all together, but should be making an effort to reduce stress when there is an unhealthy amount. The strategies we use to reduce stress can be personalized based on how an individual experiences stress. The many facets of the creative arts are ideal for treatment personalization, and this is important because not all activities illicit the same biological response for all individuals.

Serotonin and dopamine are arguably the best hormones for encouraging a creative space (Shiv, 2014). Serotonin governs whether an individual feels calm and secure, or experiences anxiety and fear, and dopamine governs whether an individual feels excited and motivated, or bored and apathetic. The proper amount of serotonin and dopamine will allow a person to live in a calm and motivational environment, thus an environment that best promotes creativity (Underwood, 2014). An increase in cortisol is known to reduce serotonin levels, potentially by increasing the expression of a serotonin transporter that elevates the uptake of serotonin (Tafet et al., 2001). Therefore, chronic stress has the ability to decrease one’s ability to live in a space of creativity.

Since the creative arts allow for treatment personalization, it is possible to find a creative arts activity that could increase serotonin and dopamine levels in many individuals. Some activities you could try out include doing yoga, drawing, creative writing, sculpting, writing music, playing music, dancing, etc. As every person is different and has individualized interests, not all of these activities will have the same effect on every person. Luckily, the creative arts allow for many options to choose from.

It is important to note that the process of creativity is executed in the same part of the brain as the process of problem solving: the frontal lobe (Kleibeuker et al., 2013). Increasing creativity can increase one’s ability to problem solve and thus increase one’s performance at a task. A human being cannot have an excess of stress hormones, such as cortisol, and be able to efficiently create hormones that increase creativity and problem solving, such as serotonin. Thus, in addition to what is learned from glucocorticoids and memory in the Yerkes-Dodson law graph, we also know from an endocrinological standpoint why decreasing stress is important for peak performance. Performing creative arts activities will activate the frontal lobe, and thus activate the part of the brain that helps one problem solve and perform.

Studies have been done which show a significant decrease in cortisol levels after multiple sessions of participating in creating art. One study published in the Journal of the American Art Therapy Association (2016) showed 75% of participants had a significant decrease in cortisol levels after 45 minutes of creating art. Another study in the Journal of Nursing Education (2005) found that incorporating a creative arts activity into the classroom environment significantly reduced stress and anxiety levels amongst the nursing students. An experiment was also conducted with girls who were living in family-like centers (Kheibari et al., 2014). For one week, half of the girls participated in art therapy, while the other half did not. The study found a significant reduction in the level of anxiety amongst the girls who participated in the art therapy. The conclusion can be made from these studies and many more like them that engaging in the creative arts has the potential to be a tool for lowering stress levels and increasing the health of those managing chronic stress. We also know from the Yerkes-Dodson law that these conclusions suggest that engagement in the arts or in art therapy could increase the work performance of those who experience stress levels that are too high.

The introduction of creative arts intervention into both professional and academic settings could be beneficial to increasing the performance of both employees and students. From a neurological standpoint, creating art has proven to be significant in decreasing stress levels amongst individuals and thus has the ability to increase the overall performance of these individuals in a multitude of life tasks. The understanding of this concept and implementation of it has the potential to be a non-invasive and enjoyable solution to stress inhibiting work. Allowing for human beings to use creativity and operate in a creative space can improve lives drastically and this concept deserves more attention. If you would like to put the concepts I have put forward to the test, I suggest you try this quick and easy creativity inducing activity. Perhaps if you are currently feeling stressed, this activity will ease your mind.

Using only circles, squares, and triangles, draw a picture in response to this prompt: What was your biggest strength today?

This activity may lower your stress, or you may want to participate in an art form more specific to your liking. Regardless, keep your mind open, and allow it to fill all of the creative spaces it would like to.