- This event has passed.

THE ART OF PRINTMAKING

January 16, 2012 - May 25, 2012

Art 276: Advanced Museum and Curatorial Studies students Rebecca Diefenbach ’13, Alexandra Doersam ’12 and Jocelyn Gurland ’13 research the history and and culture of printmaking by studying selected masters of etching, engraving, heliogravure, lithography and wood engraving from the 17th through the 20th centuries.

The Art of Printmaking

Art 276: Education, Communication and Exhibition Design introduced us to the processes of research, planning and design in a working museum. Throughout the Fall 2011 semester, we explored the works-on-paper of Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-1669) and Adriaen Jansz Van Ostade (1610-1685) in the Lehigh University Art Galleries Teaching Collection. While comparing printmaking techniques and compositional approaches, we focused on the depiction and placement of the human figure as a common element within each work of art. Our goal was to bring together diverse printmaking techniques, including engraving, heliogravure, and lithography—and to examine similarities between three distinct artists.

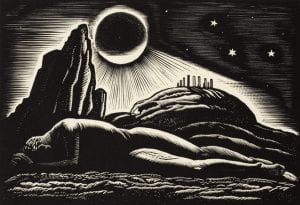

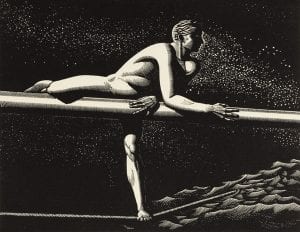

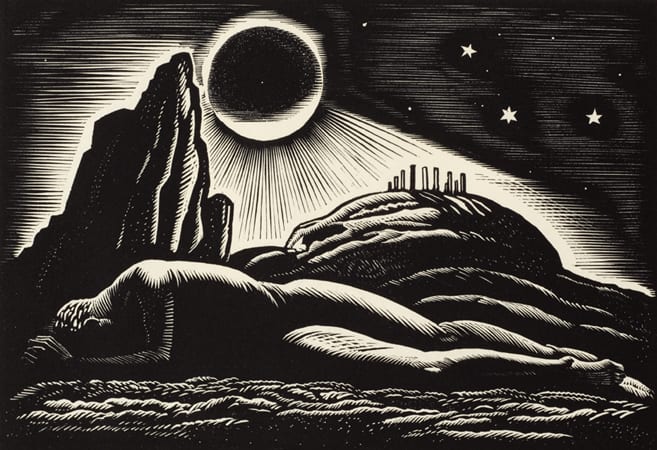

Although the prints were produced centuries apart, the depiction of the human figure serves as a point of comparison. In many of Kent’s prints we see the body of a man, usually alone in some dramatic pose. Kent simplified and idealized details and stature in order to portray a muscular machine-like body. His works display man in an active, but solitary pose while the prints of Rembrandt and Van Ostade exhibit a sense of community. Van Ostade stressed the idea of family life, village scenes and domestic work. His figures have a sense of familiarity, and are often generic and slightly cartoonish stand-ins for the characters of daily life. Rembrandt’s figures are more specific, and his scenarios more extreme: expressive portraits and self-portraits, anatomical studies, mythological subjects, scenes from private life, and crucifixions. While VanOstade uses figures to illustrate small, incidental narratives, Rembrandt’s figures become mediums for the expression of a pivotal or dramatic moment in a larger story. Kent’s figures seldom connect with daily life, remaining monumental, elemental, emblematic and eternal.

Although both Rembrandt and Van Ostade made prints during their lifetimes, the works in this exhibition are not their original production. The Rembrandt prints seen here were made by the master printmaker Armand Durand during the 19th century using the heliogravure technique. They are some of the finest reproductions of Rembrandt ever produced and are quite significant examples of printmaking in their own right.

The works of Van Ostade in this exhibition were produced by the careful observation and interpretation of 18th century printmakers who made drawings of the original paintings, drawings, and prints.

In our culture of instantaneous digital image transmission, it is important to remember the significance of prints to the people of past centuries. To view a unique and singular work of art, such as a painting by Rembrandt or Van Ostade, one had to make the long difficult journey to the city or town where the painting resided. In many cases these works were in private collections and not accessible to the public. Prints allowed multiple images of unique works to be circulated to a wider audience. Since they were relatively inexpensive to produce, prints could be owned by those outside the artistocracy. These characteristics of accessibility and plural ownership have led printmaking to be termed the most “democratic” art form.

Biographies

Through his prolific production of portraits, and scenes from literature, mythology and the Bible, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) built his reputation as a bold innovator of the Northern Baroque style. His paintings and etchings possess characteristically dark chiaroscuro lighting and highly expressive lines. Rembrandt was born into a prosperous miller’s family in the small town of Leiden, in the Dutch Republic, known today as the Netherlands. After attending the University of Leiden at the age of fourteen he pursued a career as an artist. Rembrandt trained to be a painter making his way up the traditional guild hierarchy until he achieved the status of master. He became known as an incredible teacher and trained more than fifty apprentices. Despite his successful artistic career his life was plagued by misfortune: the death of two wives and many children, and bankruptcy. Scholars see the dark emotionality and dramatic atmosphere of his best canvases as translations of this suffering. Rembrandt’s remarkable painting career is mirrored by his experimentation in etching. From 1626 to 1665, he created three hundred etchings and drypoints, handling the traditional materials in unconventional ways. He was the first to use the malleable copper plate, which allowed him to treat the plate as a canvas and create freely flowing irregular forms. Rembrandt’s beautiful etchings inspired artists to create reproductions such as those of the 19th century studio of Armand Durand which made heliogravure prints of Rembrandt’s etchings

Rockwell Kent (1882- 1971) was a painter, muralist, printmaker, graphic artist, illustrator, traveler, writer, architect, speaker and activist. Often controversial, his career was marked by its wide-ranging aesthetic, political and social impact. Born in Tarrytown, New York, Kent spent much of his early family life in and around New York City. He attended the William Merritt Chase Summer School of Art in Shinnecock, Long Island, and would later attend Columbia University and the New York School of Art. After his education, Kent traveled widely, finding inspiration in the beauty of the natural landscape in places like Alaska and Greenland. He often wrote of his adventures and travels, publishing memoirs with titles that reflected his interest in nature, such as Wilderness (1920) and Of Men and Mountains (1959). Kent used lithography, wood engraving and other forms to express his view of humanity as a struggling hero awakening to an earthbound destiny. A mystic in the tradition of Thoreau and Emerson, Kent made black-and-white images that reflect the austerity and transcendence he felt in the wilderness. In addition to fine art prints, Kent also participated in the world of commercial publishing, creating book covers and illustrations for literary masterpieces like Moby Dick and Beowulf. Because of his interest in politics and his belief in the ideals of communism, Kent’s works were shunned by galleries throughout the United States in the 1950s. At the same time, he was the first American to have his work exhibited in the former Soviet Union and was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1967. Although he lacked support in the United States, Kent remained in the country and continued to paint at his Plattsburgh, New York farm—which he named Asgaard—until his death in 1971.

An artist of the Dutch Golden Age, Adriaen Jansz Van Ostade (1610-1685) established his career painting peasants in tavern scenes and country quarters. A pupil of the Dutch master, Frans Hals (1580-1666), Van Ostade established himself as one of Holland’s foremost genre painters. Van Ostade was known for showing the poetic side of working-class life, despite the obvious effects of adversity and war. Amid undecorated and ramshackle dwellings, patchwork clothing and the scars of poverty, Van Ostade often managed to find and convey an infectious humor permeating the sports, quarrels and quiet moods of his subjects. Around 1666, he opened a workshop and took on pupils, including the notable Cornelis Dusart, Jan de Groot, Frans de Jongh, and his younger brother Isaack Van Ostade. In 1672, under the looming invasion of French troops, he sold his pictures and personal effects and set out for Lübeck, where he was rumored to have family. He got as far as Amsterdam where he continued to paint and produce his much admired work. In later years, profoundly influenced by the work of Rembrandt, he began painting Biblical scenes, and portraits of local professionals until his death in 1685. In the 18th century many of his works were reproduced and engraved by various guilds, engravers and printers.

Printing Processes

Intaglio

Almost a century after Van Ostade’s death, many of his paintings and etchings resurfaced. Printmaking was flourishing in 18th century, and many printmakers and engravers masterfully reproduced Van Ostade’s paintings, drawings, and prints through intaglio printing processes like etching, engraving and mezzotint.

Intaglio printing, like most printmaking processes, begins with the transfer of a drawing—in reverse—to the surface of a metal plate. Copper was originally the metal of choice, preferred for its softness, but in recent years zinc has become popular. Through a variety of processes, lines are incised into the metal plate:

• In Engraving, the artist pushes a burin (a small bar of hardened steel with a sharp point) across the surface of the plate, to cut away clean grooves or lines.

• In Etching, the surface of the plate is covered in an acid-resistant ground or wax material. Lines are scratched through the ground with a needle or stylus, exposing the surface of the metal. Then acid is used to “bite” the exposed areas of the plate creating a rough surface to which ink can cling.

• In Drypoint, lines are drawn directly into the plate using a stylus instead of a burin. The stylus is handled in the manner of a pencil, whereas the burin is pushed. Unlike the clean cut grooves created by the burin, the lines made by the stylus have a raised burr at their edges which gathers and holds ink in a different way. The burr is responsible for the characteristically soft, dense, feathery lines of the drypoint technique.

• In Mezzotint, technically a form of drypoint, areas of tone are created by roughening and pitting the surface of the plate with a many-toothed instrument called a “rocker.” Deeper tones are achieved through repeated passes of the rocker, while highlights may be created through burnishing and polishing the pitted surface. Mezzotint allowed artists to create tones and half-tones without resorting to hatching, cross-hatching or stippling.

Once the lines and textures are incised into the plate using the above methods, ink is rubbed onto the plate and is driven into the grooves of the lines or pitted surface. When the surface of the plate is wiped clean, the ink is held in the lines below the surface. The plate is then covered with a sheet of dampened paper and run through a press. Pressure forces the paper into the incised lines, drawing out the ink and transferring the image, in reverse, onto the paper.

Heliogravure

The prints ‘after Rembrandt’ by Armand Durand, seen in this exhibition, are some of the world’s finest examples of the heliogravure technique. Amand Durand was a great admirer of Rembrandt. He dedicated most of his life to the careful and exact duplication of Rembrandt’s images onto copper plates. Their clarity and exactness were achieved because Durand used as his guide, not the worn and dull original plates that Rembrandt created, but the best original prints available by the master. Durand’s heliogravures are in the collections of the Louvre Museum in Paris and the French Bibliotéque Nationale.

Heliogravure is a form of intaglio printing which utilizes a photomechanical procedure to transfer an image to the copper plate. One of the oldest methods for reproducing photographic images, the heliogravure process was invented by 19th century scientist and pioneer of photography, Joseph-Nicéphore Niepce around 1826.

In heliogravure the plate is coated with a photo-sensitive layer of asphaltum, also known as Bitumen of Judea. In order to transfer an image to the plate, the asphaltum must be exposed to light under controlled conditions. Unlike ordinary photography—in which light passes through a negative image—the heliogravure technique depends on light passing through a positive image. An appropriate positive image may be created in a number of ways, including applying wax to a drawing on paper so that the white areas become translucent, or transferring the image to glass using various resist techniques. The prepared image is then placed directly on top of the plate and exposed to light or sunlight in the manner of a contact print. Light, passing through the white or clear areas of the original, causes the asphaltum to harden, while the areas darkened by the lines and tones of the drawing remain soft. After exposure, the plate is washed in a solvent to remove these soft areas. The remaining asphaltum acts as a resist when the plate is immersed in acid. The plate is then cleaned, inked and printed following the processes of intaglio printing.

Lithography

Invented by Bavarian playwright, Alois Senefelder in 1796, lithography is a printmaking method that uses a stone or a metal plate with a smooth surface. Because of this smooth surface, or “plane”, it is sometimes referred to as a “planographic” printing process. The surface plane remains intact throughout the printing process, making lithography distinct from other approaches—like relief or intaglio printing—where the surface is scratched or cut away. Instead, lithography relies on the incompatibility or resistance of grease and water to transfer the image from stone to paper. First, the artist draws an image on the surface of the stone with a greasy substance called “tusche.” Later the stone is soaked with water and ink is applied. The ink sticks to the greasy image but not to the other areas of the surface which are wet. A sheet of paper is carefully laid across the surface of the stone and the ink image is then transferred to the paper (in reverse) using pressure applied by a press.

Relief Printmaking

In relief printmaking, the surface of a wooden block or metal plate is carved, gouged or cut away, leaving behind flat areas of the surface which will receive ink. Using a roller, the printmaker applies ink to the block in a thin film. Because the cut-away areas are recessed, the roller passes over them and they do not receive ink. Ink is deposited only on the uncut portion of the block’s surface. Paper is then placed onto the inked block. Pressure is applied from behind by polishing the back of the paper with a smooth object. This transfers the ink from the block to the paper, creating a mirror image of the cut design. Sometimes a press is used to supply pressure. Woodcut and linoleum cut are two well-known examples of relief printmaking.

Rockwell Kent produced many prints through a specific technique called wood engraving. In wood engraving, the printmaker uses the end-grain surface of the wooden block as opposed to the usual face-grain. The end-grain is much finer and lacks the characteristic texture of the face grain. While some methods of woodblock printing—like the Japanese woodcut—often include the naturally occurring texture of the grain within the design of the print, wood engraving seeks a smooth, uninflected surface that allows for greater detail within the carving, finer lines, and therefore a wider range of tonal effects. The wood engraver uses a sharp tool called a burin (or graver), commonly associated with intaglio printmaking. Typically, the printmaker holds the burin in one hand and the wood block in the other, steadying the tool while moving and turning the block itself. Although boxwood is typically used due to its de

nse, fine grain—many of Kent’s pieces are made with maple. Since wood engraving requires such precise attention to detail, many artists working in this technique choose to make smaller works.