- This event has passed.

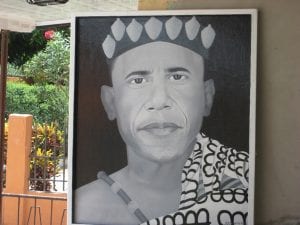

AFRICAN VISIONS OF BARACK OBAMA

August 29, 2012 - December 9, 2012

Presented in conjunction with the South Mountain College Seminar Fall 2012.

All works are courtesy of George Jevremovic, Material Culture, Philadelphia

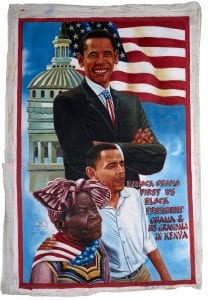

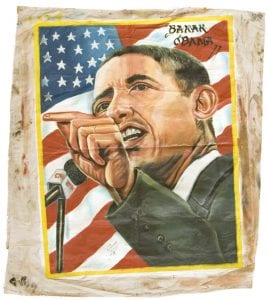

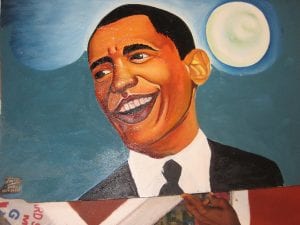

Barack Obama’s journey in the African imagination began well before his November 2008 victory, gaining momentum in the hearts and minds of many across Africa with every CNN broadcast and daily headline, a sort of parallel offshore election won in a landslide before a single real vote was cast in the United States. Sensing that something so seismic, so public, and yet so personal for so many, would find fertile ground among African artists, our idea was to locate, collect and exhibit a group of artworks created during and leading up to Obama’s first year in office. — George Jevremovic

Curatorial Foreword/ Norman Girardot & Ricardo Viera

In the Beginning

The curators are honored to present this extraordinarily colorful and culturally provocative exhibition. But we are only handmaidens to its existence and we must tell some of the story of its genesis. We are greatly indebted, therefore, to the prescient vision, ethnographic curiosity, artistic sensibility, and entrepreneurial bravado of George Jevremovic and his associates. Jevremovic is the founder and guiding spirit of a unique Philadelphia cabinet of curiosities known as Material Culture. Jevremovic is truly as much an anthropologist as he is a merchant of the wondrous variety of human creativity. Indeed from his beginnings as a purveyor of Turkish rugs as material objects of utilitarian function and artistic beauty, he has promoted not only cultural treasures but also individual artists from around the world (such as the Nigerian painter Twins Seven Seven, 1944-2011, and the African American bottle cap artist Mr. Imagination/Gregory Warmack, 1948-2012).

Jevremovic astutely recognized the cultural and artistic significance of America’s first black president for Africans and had the resources in 2009 to go to Africa and witness this incredibly diverse, proudly hopeful, playfully serious, and commercially significant outpouring of the collective African soul. What we see in this show in 2012 is the fruit of Jevremovic’s probing, and ongoing, explorations in Africa and his wisdom in making these visions available to all of us. Jevremovic is also an accomplished creative writer and essayist who all too often had little time to devote to his craft. In 2009, however, he was driven to write an extended essay describing his adventures in Africa and his reasons for bringing these works back to this country – not to sell them but to educate us about the visionary dreams and aspirations of other cultures. And by so doing, we believe that his assemblage of this art teaches us something important about ourselves and the global power of images.

While Jevremovic was our original inspiration and source for the artwork, we here at Lehigh University are wholly responsible for the current design and contextual presentation of this exhibition in the Fall of 2012. We especially thank the LUAG design team of Mark Wonsidler, Jeffrey Ludwig, Khalil Allaik, and staff. Because of the educational and cross-cultural nature of the material, we have specifically linked this exhibition to a special seminar course in Lehigh’s experimental South Mountain College. This is a course that asks our students not only to learn the value of seeing the world from different cultural perspectives, but also to be responsible for putting together a broad educational program appropriate for children and an adult general audience.

The Power of Images

The power of visual images in shaping our understanding of the world cannot be denied. In this sense, images can obviously be used manipulatively for political purposes. Think for a moment (better yet let your imagination conjure up the images or perhaps best just go ahead and Google them) of such indelible left and right images as the infamous “Daisy” ad during the 1964 presidential campaign or the Michael Dukakis on the tank ad in the George H. W. Bush election of 1988. These propagandistic and polarized image wars have become even more pointed in recent years with the presidency of Barack Obama. To take but two examples, recall Shepard Fairey’s striking street art “Obama Progress/Hope” image (appropriated or purloined depending on your degree of toleration for postmodernist mash-ups) or, even more notoriously, the Firas Alkhateeb “gone viral” rendition of Barack Obama as Batman’s smeared lipstick Joker. Now it may be said that, during an election year, anything goes or, conversely, that anything that lends itself to the malicious distortions of negative political imagery should be avoided.

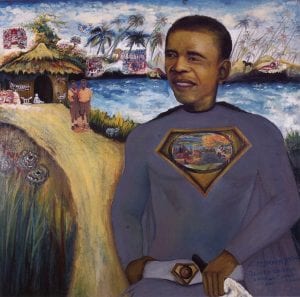

We see this exhibition differently. Firstly, the imagery is not American, nor has it been appropriated by any particular American party. Furthermore we are dealing largely with joy and not malice. The simple truth is that there is much to be learned here about the way images are used in all cultures and in every possible positive, commercial, emotional, frivolous, humorous, and hopeful way. Even more significant is that, as George Jevremovic has said, these particular images represent a fascinating “journey into the African imagination.” These concerns should be part of the educational mission of

Dreaming with Our Brothers and Sisters

This exhibition is not about Barack Obama. It is not about the current presidential election. And it is not about taking sides during a political year. It is about Africans and the revelatory power of the visionary imagination. Most of all this is an educational venture, an effort to promote a reflective understanding that comes from seeing what is right in front of our eyes as filtered by other cultural perspectives and dreams. It has primarily to do with the morality of empathetic knowing – to see the world as others see it. This is the ability to know that by imagining the world through different cultural lenses we simultaneously learn something about that other culture, about ourselves, and about the deepest and most responsible art of seeing and knowing.

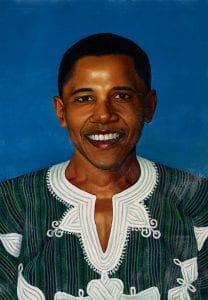

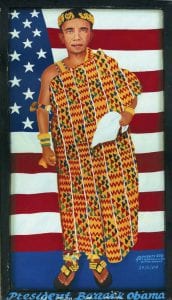

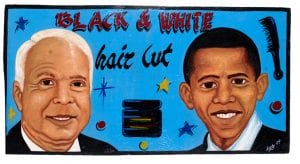

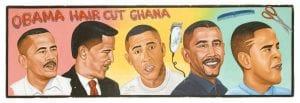

What we have in this exhibition is not so much a display of what Westerners like to think of as “fine art” or “political art,” but arresting visual examples of a folk wisdom coming from all sorts of common African people. The issue, to take one lowly but telling example, is not whether Barack Obama is sometimes shown in native African garb. Rather the issue is whether we can imagine, rejoice, laugh, and learn from the possibility of Obama, or any other American leader (black or white or black and white), ever having an African-styled Obama-rama-haircut as shown on the truly ubiquitous and gloriously funky hand-painted barbershop signs. We need, then, to learn to dream freshly-styled dreams about ourselves and others along with our African brothers and sisters.

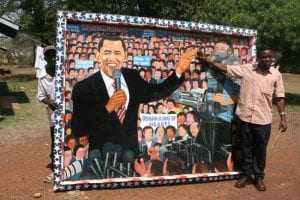

Excerpts from George Jevremovic’s 2009 Essay “The Dream”

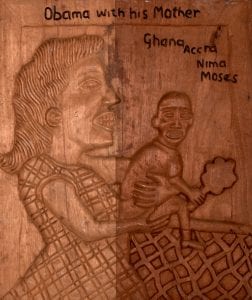

Welcome proof that there is no such thing as “the art world,” only worlds of art, are the legions of folk and popular artists in Africa, from Ghana to Kenya, Togo to Mali, whose painted works on board, canvas, metal or wall surface—seen daily by an audience of millions—provide visual branding and identity to thousands of small businesses and enterprises: beauty salons, tailors, cinemas, grocery stores; on and on. . . . .For a first-time visitor, it can be exhilarating and shocking: global and local brands, African and non-African celebrities and international icons; all appropriated and rendered in a mosaic of popular and homegrown styles, languages and regional dialects; all competing for the attention of the passerby. Many are signed and dated or feature a studio’s logo, and every day more of them display cell phone numbers and e-mail addresses drawn with the fluid skill of a calligrapher.

Traveling to West Africa in the 90’s in search of traditional textiles, artifacts, carvings, I felt that nothing made a greater impression—from city to countryside—than the signs, banners, portraits and messages along the way. Veering from service-oriented to visionary, product-focused to didactic, informative to apocryphal, they were testament to the fact that human creativity is as abundant as it is uneven. . . . While commissioned works by definition fit the specific needs of clients, many—particularly those made to showcase the roadside venues of the artists themselves, or which lean casually upright in a corner of a studio—reveal a strong spirit of “art for art’s sake.” Such works are filled with personal agendas, irony, politics, word-play, invention, and an impulse to think outside the margins and stay a step ahead of the pack.

When art forges deep connections in the cauldrons of commerce and culture, in places like Nima and Teshie (two thriving communities of Accra), categories blur into new focus, releasing talent and vision, turning western concepts of art as luxury upside down, or—more aptly—inside out. . . . .What remains constant, what keeps filling the oncoming, clattering void of market days and processions, is the energy of communities of artists to adapt and change, to serve the pulse and needs of a real audience, with work meant for—mostly—outdoor display. Interestingly, in many places—especially in West Africa—demand has increased rather than diminished over time, reflecting the growth of small businesses and enterprises that find the hand-painted sign an affordable, aesthetically preferable alternative to the machine-printed one. Exhibitions in recent decades at international museums and galleries, along with the publication of books, articles and catalogues, have raised public awareness of what can objectively be described as one of the most vibrant, popular—not to mention entrepreneurial—grassroots art movements in the world.

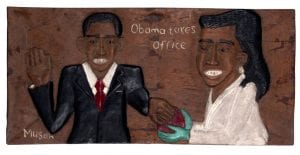

[I] hope [seeing these images] will add to a growing appreciation and understanding of folk and popular African art, with a twist that is timely and could not have been predicted: the election of Barack Obama as the 44th President of the United States of America. [My] idea was to locate, collect and exhibit a group of artworks created during and leading up to Barack Obama’s first year in office, sensing that something so seismic, so public, and yet so personal for so many, would find fertile ground among African artists. We were not disappointed. [Indeed the African production of Obama images has continued unabated down to today. What will happen in Africa after the election remains to be seen.] . . . .If these are historic and challenging times for the “most powerful nation in the world,” and for the world in general, then they are acutely so for Africa in particular. What happens in America doesn’t stay in America, and what happens in Africa doesn’t stay in Africa.

Seen here is the public Obama, who carries on the “legacy of hope,” who on his first visit to sub-Saharan Africa as President, said: “Fifty-two years ago, the eyes of the world were on Ghana. And a young preacher named Martin Luther King travelled here, to Accra, to watch the Union Jack come down and the Ghanaian flag go up. Dr. King was asked how he felt watching the birth of a nation. And he said: ‘It renews my conviction in the ultimate triumph of justice.’ “ (Accra, Ghana, 11 July 2009). . . .Artistic license doesn’t end in a merely public Obama, an event personified, but includes the personal and the kitsch, dreams and visions, sincerity and self-promotion, success and failure, the good, the bad, the beautiful, the borrowed, and—occasionally—the audaciously original. Sounds like art imitating life—and politics!

If Obama’s journey in the African imagination, like his presidency, is a work in progress, it comes as no surprise that his victory, in hearts and minds across Africa, arrived well before November 2008, gaining momentum with every CNN broadcast and daily headline, a sort of parallel offshore election won in a landslide before a single real vote was cast in the USA. It’s a given that the Obama brand would start an avalanche of faux products and political endorsements, bogus associations of every stripe and flavor. But he is not the first American president subjected to artistic scrutiny or commercial appropriation on foreign shores (In the 1960’s, JFK’s likeness was a favorite among pictorial carpet weavers in Iran), and he likely won’t be the last. There are flocks of Clintons (especially in Ghana) and even the occasional Bush. On a sliding scale, Bob Marley, Jesus Christ, Michael Jackson, Kofi Anan, Che Guevara and Nelson Mandela may still cover more surface, though it’s easy to see the cellular structure of the whole canvas changing, adding Obamas by the day.

As an elected American official, Obama’s message to Africa has been consistent, supportive, carefully diplomatic, so as not to raise hopes that change in Africa will come from anywhere but Africa itself: “We must start from the simple premise that Africa’s future is up to Africans.” Fair enough. When he tells an African audience that the future, the world’s future, depends upon “transformational change,” he does so in the context of one whose own life story raises the bar of what is imaginable, not just possible.

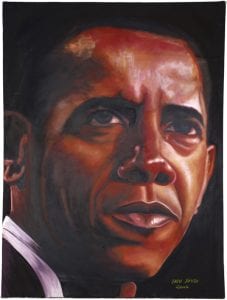

[An especially intriguing work] that elicits comparisons and questions [regarding both the imaginable and the possible] is the unfinished portrait of Obama by the artist Sheff (see reverse poster). Its resemblance to Gilbert Stuart’s (1755-1828) unfinished portrait of George Washington (National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; Boston Museum of Fine Arts) is hard to ignore.

It’s worth telling how [I and my associates] came to acquire it: a few hours after attending Obama’s speech in Accra [in July 2009], when the world’s press was focused on the historic symbolism of the First Family’s journey up to Cape Coast (the centuries-long “gate of no return” for countless Africans sold into slavery), we happened on a roadside studio where a young artist in his 20’s was displaying three Obamas: one of a jubilant husband and wife in a victory embrace; the second, a flattering portrait even a mother could love, set against a background of skillfully modulated, official-looking, strobe-lit grays, a flag pin balanced carefully on a lapel. . . It was the third, the unfinished one, however, that drew our attention the most; its raw poignancy seemed to simultaneously capture the poetry of the moment and to hit the nail on the head. Unlike Gilbert Stuart, who kept his unfinished portrait of Washington as a model for future Washingtons (including the one on the dollar bill), Sheff offered to complete his Obama. He seemed amused more than surprised when we told him that we’d be happy—as long as he agreed—to purchase all the paintings as we found them. “No problem,” he replied. When we asked about the resemblance of certain of his paintings to images in the news, Sheff enthusiastically opened a drawer stuffed with clippings from magazines and newspapers, explaining to us that while photographs had always provided him valuable source material, his desk had never been fuller than it was that afternoon in July.

However much Barack Obama is the subject and focus, the muse and occasional lightning rod, of a growing body of African folk and popular art, and however much these works may be seen to celebrate the unprecedented fact that an American with an African father was elected to the White House, . . . it is the ideas embodied in them that are the real work in progress, inspiring the artists and commanding the attention of an audience of millions.