- This event has passed.

Pre-Columbian Artifacts

August 26, 2013 - June 30, 2015

The term “Pre-Columbian” has expanded to include the period before before indigenous cultures came under the control and influence of Europe, sometimes decades and even centuries after Columbus’ arrival in 1492. These objects provide a glimpse into the daily life of Pre-Columbian peoples, including the Chavín, Nazca, Moche, Tairona, Chimú, Taíno, and Inca. This exhibition is a project of Advanced Museum Studies students: Susan Wigodner ’10, Alex Doersam ’12 and Idelis Matias ’12.

Chavín 1000 BCE-200 BCE

Believed to be one of the first examples of a stratified society, the Chavin culture dominated the Early Horizon Period of Peru. Located in the Central Andes, the Chavin were organized around religious elites who made claims to divine connection. This group is associated with a archaeological site known as Chavín de Huantar, a temple-like structure that was most likely a religious and ceremonial center. Carvings at this site show figures wearing elaborate headdresses and blowing trumpet-like instruments. Other sculptures depict human-to-animal transformation, an aspect of the Chavín belief system. It is believed that these ceremonies were enhanced by the use of hallucinogenic drugs.

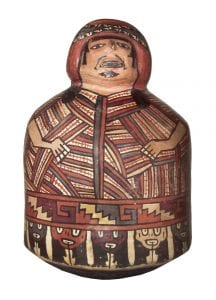

Moche 50 CE-800 CE

Developing out of the Chavín culture, the Moche culture is noted for its political, ideological and artistic innovations. Situated in the north Peruvian desert valleys irrigated by rivers flowing westward from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean, the Moche pioneered new technologies in metallurgy, pottery, and textile production. Ritual human sacrifice and the consumption of blood is believed to have played a major role in their religious life. Costumed high priests and other elites would sacrifice prisoners and drink their blood, while portraying a warrior deity, a jester-like goddess or a bird god. The decline of the Moche culture is thought to have stemmed from severe climate changes. These changes may have undermined their belief in the power of human sacrifice to influence their gods.

Nazca 1 CE-700 CE

Located on the Southern Peruvian coast, the Nazca culture flourished in the Early Intermediate Period. They built impressive systems of underground aqueducts known as puquious. Heavily focused on agriculture and fertility, the Nazca belief system venerated the “three sisters”: maize, squash and beans. Their society was made up of local chiefdoms centered around a ceremonial complex, Cahuachi. The Nazca culture’s most notable creations were geoglyphs, or earth drawings, called the Nazca lines. These enormous line drawings, made of raised earth and stones, could only be deciphered from the air. From this vantage point, the drawings can be seen to depict both animal figures and simple lines connecting sacred places.

Chimú 1000 CE to 1450 CE

The Chimú culture emerged from the remnants of the Moche people in roughly the same territory along the coast of northern Peru. There are many links between the two cultures, such as the production of burnished blackware pottery in the form of animals or human figures, as well as the creation of intricately detailed metalwork. Unlike the sun-worshipping Inca, who later conquered them, the Chimú worshipped the moon (Si) and thought of the sun as a ‘destroyer’. Research suggests that the Chimú may have practiced dual rulership where two kings representing different kinship groups ruled at the same time.

Inca 1200 CE to 1532 CE

Originating in Peru during the Late Horizon period, the Incan culture was the largest empire in Pre-Columbian America. The Incan name for their empire was Tawantinsuyu, which suggests “four regions” or “four united provinces.” At the center of the empire was the city of Cuzco, an administrative, political and military hub. Cuzco was also the religious center of Incan sun-worship, and the site of human and animal sacrifices. The Incas believed in reincarnation and viewed their emperor, or Sapa Inca, as the divine “child of the sun.” The use of agricultural land was divided among the aristocracy, the religious establishment, and the farmers who worked the land for all three groups. Civil war and smallpox prompted the initial decline of the empire before its final conquest by Spanish colonial forces.

Tairona 700 CE to 1600 CE

Occupying a series of large villages on the northern Colombian coast, the Tairona established an economy based on corn and manioc farming. Stone construction was very common, as seen in numerous houses, tombs, bridges, and terraced platforms. They also constructed roads and canals, in addition to irrigation systems. The Tairona are well known for their metalwork in gold, copper and a gold-copper alloy (tumbaga), as well as their ceramics, stone utensils, and ornaments made of bone and shell. Violent conflict and forced assimilation by the arriving Spanish colonists led to their decline. However the indigenous people known as the Kogui, Wiwa, Arhuacos and Cancuamo are believed to be direct descendants of this culture today.

Taíno 1000 CE-1500CE

A seafaring people found throughout the islands of the Caribbean, the Taínos were one of the first groups that Christopher Columbus encountered upon his arrival. This agricultural society cultivated, among other things, cotton and palm which were used in the production of fishing nets and ropes. Dugout canoes (kanoa) were produced in various sizes and some could accommodate up to 150 people. Their highly developed civilization was divided between a common class and nobility led by a male or female cacique (chief). Their religion centered on the worship of cemís: gods, ancestors or spirits often represented as carved animal forms. The Taíno believed themselves to be descended from one such cemí, the culture hero Deminán Caracaracol. Although Spanish documents suggest that the Taíno were driven to extinction through starvation and disease by the 16th century, today many people living in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic identify as descendants of this culture.