- This event has passed.

FACEWORK

FACEWORK AMERICAN CERAMIC VESSELS FROM THE SOUTH AND THE NORTH

But now, O LORD, thou art our father; we are the clay, and thou our potter; and we all are the work of thy hand. Isaiah 64:8 KJV

Genesis

Long before Facebook’s digital facework, people were captivated by representations of the human face. From prehistory until now, there have been anthropomorphizing traditions that saw faces in the clouds and in other ambiguous forms of matter. These foundational experiences led to the use of pigment, stone, wood, and clay to make facial likenesses. It is therefore the plasticity of visual matter, like the linguistic and musical pliability of sound, which is intrinsic to the symbolic creation of the human world. As recorded in the Hebrew bible, to be human was to be made from the celestial breath of the sky and the amorphous clay of the earth. In fact, according to these Abrahamic scriptures, we were fashioned in the image and likeness, the protean visage, of the Great Potter, the Lord God. Or as other traditions would declare, the creation of humankind and the world of utilitarian objects (their ubiquity flowing from the malleability of the earthen clay and their usefulness as containers) could only stem from the pregnant creativity of the Great Mother Goddess who inhabits the womb-like hollows of the Earth. Whatever one’s religious and cultural background, whatever the mythic story of meaning, the human face has always been the distinctive material manifestation of spirit and personality. All human life is, in many ways, a matter of imaginatively recognizing the manifest and hidden messages revealed by the myriad faces and facets of bodily existence on and in the earth.

American Tradition

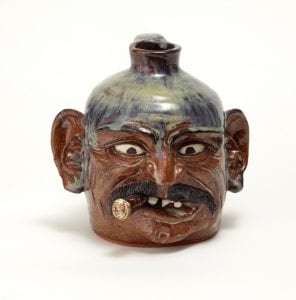

In this exhibition we see a fascinating manifestation of this universal human impulse to find both sacred and profane meanings in the creative facework of our physical and emotional lives. Our focus is on a particular American cultural production of ceramic face vessels popularly known as face jugs or sometimes more quaintly as ugly jugs. These wonderfully expressive vessels are mainly associated with Southern potting traditions in the Piedmont area of North Georgia and parts of South and North Carolina from the end of the 19th century down to today. The origin of the vessels is still a contested issue. Some argue (with mounting evidence) for their roots in ritualistic aspects of African slave tradition associated with the Edgefield district in South Carolina before, during, and after the Civil War era (1861-65). Others propose a more eclectic German and English-Scottish genesis associated with both the North and the South. Moreover, American Indian ceramic tradition may also be an additional, although largely neglected, factor.

The current popularity and efflorescence of these vessels as folk collectables and tourist art dates to the 1960-70s when the Smithsonian Institution in the form of an ongoing series of Folklife Festivals started to seek out, encourage, preserve, and celebrate dying folk crafts throughout the United States, especially in the American South. This accelerated an earlier Euro-American tradition in Georgia and the Carolinas of making a kind of non-utilitarian ‘art pottery’ with often semi-grotesque faces expressive of what has been called a ‘masculine ‘aesthetic of the ugly’.” More recently from roughly the 1980s onward, the popularity and monetary value of these vessels has increased because of their affinity with the so-called outsider art movement associated with “contemporary folk,” self-taught, vernacular, rural, or otherwise marginal artist-craft practitioners. As with aspects of the overall outsider field of art, the increased marketability and popularity of these vessels has given rise to a genre of sometimes overly generic, cartoonish, and kitschy jugs. At their best, however, and very much like the best folk, outsider, and self-taught art, these jugs directly and personally communicate with the viewer. Somewhat like an aesthetic encounter with a good poem, a meeting with a good face vessel “is like meeting a person. The more like that it is, the better the poem [or jug] is.” Moreover, the better it is, the longer you remember the experience, the “longer it lasts.” It is, indeed, a straightforward face-to-face interaction with these jugs that can conjure the presence of another soul – whether living or dead, real or imagined, virtuous or demonic.

Southern Face Jugs

Most important with respect to the upsurge of interest in Southern ceramic face vessels was the popularity of the north Georgian Lanier Meaders’ (1917-1998) eccentric jugs as shown at the first Folklife Festival in Washington D.C. in 1967. The Meaders clan in Mossy Creek, Georgia, as descending from Casey (1881-1945) and Cheever Meaders (1888-1967), had ties with the Hewell family of Gillsville, which (according to the leading expert on Georgia folk pottery John Burrison) most likely picked up the idea of the jugs by intermarrying into the Ferguson clan whose ancestor Charles H. Ferguson (1793-1878) migrated to Gillsville from South Carolina. Charles H. taught his grandson Charles P., or Charlie, Ferguson (1850-1917) a kind of jug making that probably embraced Edgefield elements from both the slave tradition and the white tradition represented by Thomas Chandler’s (c. 1850s) more European-style face pots. For early 20th century white potters of face jugs such as Charlie Ferguson – as well as for some later white potters practicing an “ugly aesthetic”- the jugs were often characterized as innocent “whimsies.” The more disturbing side of this designation is its association with quite un-whimsical racist stereotypes suggested by J. A. Palmer’s “Aesthetic Darkey” stereoscopic photograph from 1882 showing a young African American boy contemplating a sunflower in an Edgefield-style face jug. This photograph was clearly a reinterpretation of an 1882 Harper’s Weekly cover engraving entitled “The Aesthetic Monkey” which satirically depicted a Darwinian monkey dressed in foppish clothes while fawning over a sunflower. The Harper’s engraving was commenting on a controversial lecture tour in the United States by the famed literary libertine Oscar Wilde who was mocked for what was seen as his regressive aesthetic theories suggested by his signature sunflower. A similar prejudiced note characteristic of general cultural assumptions at the time was struck by turn of the century comments about uncivilized jugs with “coarse” and “weird” human faces by the pioneering ceramic historian Edward Atlee Barber.

It must be admitted that Lanier Meaders’ jugs, and much of the jug making provoked by Meaders’ success, were more imaginatively quirky and satirically capricious than they were either overtly or covertly racist in nature. Whatever the inspiration for the kinds of faces depicted, the fact is that the making of face jugs during the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st century has spread out to include numerous (mostly white and male) potters operating in north Georgia’s Cleveland-Mossy Creek area and in the Gillsville-Lula region – as well as to other areas in Alabama and the Carolinas. Notably prominent have been the potting centers in the Catawba Valley and Seagrove, North Carolina, as seen in the early jugs by Harvey Reinhardt (1912-1960) and the work of influential masters like Burlon Craig (1914-2002) and the inventively versatile Billy Ray Hussey (1955- ).

As the folklore scholar, Henry Glassie, has said:

The story is that the face jug was developed by slaves who worked as potters in South Carolina. Then the idea was carried up to the highlands and assimilated into the Appalachian cultural mix. It used to be acceptable to write of the Anglo-Saxon purity of the mountain people, but Lanier Meaders spoke proudly of his Native American ancestry, and the face jug seems to be, like the banjo, an Appalachian trait with an African-American origin. The potters, at least, find the idea reasonable.

Yes, this is very reasonable as stories go, as well as interesting with respect to the analogy with the African-American and Appalachian heritage of the banjo as that quintessentially folksy and African spirit-fraught musical instrument. Equally beguiling and interpretively significant is the growing evidence that dramatically highlights the important role of black slaves working in Edgefield, South Carolina pottery factories who made jugs in a riffing remembrance of the Kongo shamanistic or “conjure” tradition of ritual prophylactic “power” objects imbued with the spirit, and “face,” of ancestral spirits (such as the nkisi). This is a kind of insinuating and spiritually evocative facework (or soundwork thinking of the banjo and the blues) that connects all of us -black and white and of every rainbow hue and gender modulation – into a common human community.

Roundabout the South and the North

During the last few decades of the 20th century and now into the 21st century, the Southern tradition of face jugs has started to influence a new generation of Northern potters and collectors. As already suggested, this is not an entirely new development since from the 18th and 19th centuries there has been a back and forth flow of folk and academic potting lore between the North and the South. This pertains to various aspects of ceramics, but also with respect to face jugs and the impact of Northern centers in Pennsylvania (Philadelphia in particular as associated with decorated stoneware from the Remmey Pottery in the 19th century), New Jersey, New York, and Ohio. As provoked by the mystery of her grandfather’s odd “ugly jug” found in Philadelphia, April Hynes’ work on the Wanderer slave ship project suggests that there was a movement of face jugs from the South to the North among run-away and emancipated slaves toward the end of the Civil War. Even more significant was the great northern migration of African Americans during the first half of the 20th century. A fascinating example of the back-and-forth movement of jug tradition involving black Americans is the story of Jim McDowell (1946- ), a face jug maker who currently resides in Ashville, North Carolina. McDowell’s peripatetic movements are interesting since as the distant nephew of a slave potter in Jamaica, he moved from Virginia to Washington D.C. during the mid-century struggle for Civil Rights. Then as a Viet Nam era veteran stationed in Germany, he learned about ceramic technique from potters in Nuremberg. Returning to the United States and feeling drawn to the ministry, he ended up in Johnstown, Pennsylvania where in the 1980s he started to make face jugs that recalled his ancestral roots and the practice of inscribing pots in the manner of the famous Edgefield potter, “Dave the Slave.”

The time has come to recount some of the story of my own ethnographic romance with these curiously charming pots as a way to introduce the other northern potters in the Lehigh exhibition. It is also important to recognize the technical and aesthetic continuities of these different regional potting traditions as well as the creative distinctiveness of the Northern potters. My discovery of the Southern tradition goes back to the early 1990s when I was visiting my younger brother, Steven, who had just moved from Atlanta to the felicitously named north Georgia town of Flowery Branch. As it happens, Flowery Branch is directly adjacent to the north Georgia centers of potting tradition (particularly Mossy Creek/Cleveland and Gillsville/Lula). Given my previous interest in Georgia folk and outsider art, it quickly became a special pastime for my brother and me to seek out various well-known and obscure potters in the area – a practice that he and I have continued for more than 20 years. I have always considered myself a historian of religions with a scholarly interest in outsider and self-taught art. In this sense, I would claim that my primary interest was in the stories of the artists and the meaning of the work rather than the objects themselves or their monetary value. Over the years, however, I have haphazardly acquired a large number of jugs; and it would be disingenuous of me to say at this point that I am not a collector and that my interest is only academic. Nevertheless, I am still vitally interested in the historical, cultural, and artistic legacy of these vessels. In many ways, therefore, this exhibition brings these two motivations of understanding and collecting together. And this is a convergence that is, in truth, always manifest in the very best and passionate collectors and scholars. Scholars may live within their abstractions but they truly (although often covertly) lust after the haunted facticity of the things themselves. Abstractions are just the templates of the deeper interconnected reality of thoughts and things.

In the midst of seeking out and interviewing the north Georgia potters in the late 1990s and early 2000s, several of the potters (chiefly those in the Gillsville and Mossy Creek area) would invariably ask me, upon hearing that I was from Pennsylvania, whether I had ever met a Pennsylvania potter who had spent many years in north Georgia learning the skills of traditional folk pottery (utilitarian ware such as garden pots as well as face jugs). The name invoked was Amedeo Salamoni (1965- ) – his given name pronounced as “ah-mee-dee-o” without any real Italian accent and rhythm. I assured my Georgian interlocutors that I had never heard of Salamoni back home. However my interest was sparked by the fact that the Georgia potters were obviously impressed by this northern college boy, trained in the academic tradition of ceramics, who rode down on his motorcycle to learn the arcane country ways of Southern potting. They liked his persistence and work ethic, but they were especially impressed by his technical abilities in throwing a pot, his fascination with wood-fired kilns, and his evolving aesthetic flare. This Ah-mee-dee-o quickly learned to emulate the Georgia masters of face jugs, but also over the years, he started to develop a more fluid and expressive, less stereotyped, facial style with his pots. And this is an aesthetic evolution that continues to unfold today.

At some point in the early to mid-2000s, I discovered Salamoni’s whereabouts in Pennsylvania (first outside Oxford and now Quarryville in Amish country near Lancaster) and was delighted to learn that he had made his own wood-fired kiln in the manner of his Georgia mentors and was turning out traditional style stoneware and face jugs. At about the same time, I met the black potter Jim McDowell in Johnstown where my son was going to school at a branch campus of the University of Pittsburgh. Shortly afterwards, I heard about the work of the potters Wes Muckey (1970- ) and Greg Zieber (1962- ) who had a show of their face jugs at the Reading community art center known as the GoggleWorks. Muckey and Zieber had learned the art of ceramics independently but met while working on traditional red ware at the Breininger Pottery in Robesonia. Somewhat later, they started their own pottery business in Nolde Forest in Mohnton focusing at first on traditional Pennsylvania Dutch redware along with forays into pop imagery ceramic pieces for rock band and biker aficionados. Because of his grandmother’s Southern roots, Muckey became fascinated with Southern face jugs and along with Zieber started to make a technically accomplished and innovative redware series of both traditional and untraditional facial vessels. The production of these jugs most often involves Zieber throwing the pots and Muckey sculpting the faces, a process that then involved firing in an electric kiln and the use of vivid commercial and hand-mixed glazes. Lastly at some point in the late 2000s, my wife and I were visiting the Museum of American Glass at the Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center (formerly Wheaton Village) in Millville, New Jersey when we met the potter Phyllis Seidner (1961- ). She had learned the craft of potting from the ceramic artists at the Center and eventually began to experiment on her own with making face jugs. Over the past half-decade or so, she has developed her own facial style on the pots and has started to make both miniature jugs and facial teapots.

The Reciprocating Gaze

Finding the northern face jug makers Salamoni, McDowell, Mucky, Zieber, and Seidner only underscores the adage of “seek and ye shall find.” Another surprising example of this principle is the famous bottle cap outsider artist Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack, 1948-2012) who started making his own plaster-bottle self-portrait versions inspired by the Southern face jugs he observed when in 2001 he moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I have no doubt that there are other potters in the North who are producing interesting variations on the Southern tradition of face jugs, some of which may be truly inventive and distinctive. Indeed it will be interesting to see what other potters may come to light in the North – particularly if they happen to be practicing black potters like McDowell or women potters like Seidner. With regard to women face jug makers it may be noted that although men have dominated the Southern tradition, there were always creative women potters like Grace Hewell, Georgia Blizzard, Anita Meaders, Marie Rogers, Mary Ferguson, and Lin Craven.

While we should be concerned with the cultural, historical, geographic, ethnic, and gender aspects of face jugs, the final and deeper truth of these vessels, whether from the South or the North, has to do with the aesthetic response they so spontaneously and strongly call forth when we look into their faces. We have, therefore, provided some of the crucial historical and cultural context for understanding the source and provenance of these objects. At the same time, we want to emphasize that our primary goal in curating this exhibition was to elicit an unfiltered aesthetic response from the observer. It is the north gallery wall of only jugs and faces that creates an expectation of what we might call the “reciprocating gaze.” These are not passive objects. They watch us as we gaze upon them. The clay is animated with the passion of the artist and with what was released from the earthen matter. To look into the eyes of these vessels is, then, to engage in an almost personal dialogue with American cultural, spiritual, and artistic history with all its vicissitudes of darkness and light. As Henry Glassie reminds us, it is the dynamically focused passion in any medium that transforms tradition and technique into art. This is, after all, a crafty artistic tradition involving an interactive facework which, with expressive power and often humor, winks meaningfully back at us.

Norman Girardot, University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Lehigh University

Amedeo Salamoni / Expressions: My Journey Making Face Jugs, video by Steven Lichak.

Facework Symposium: Arthur Goldberg, April Hynes, Norman Girardot