- This event has passed.

Purvis Young, Howard Finster, Charley Kinney & Echo McCallister

Selections from the LUAG Teaching Collection.

Works on paper from four notable Outsiders, featuring a gift of works by Howard Finster from the Thomas E. Scanlin collection.

WHAT IS OUTSIDER ART ?

The development of the awareness of forms of creative expression that exist outside accepted cultural norms or the realm of “fine art” began with the researches of psychiatrists early in the 20th century.

French artist, Jean Dubuffet became interested in these studies of the art of the mentally ill–which he termed art brut (“raw art” or “rough art”). Dubuffet admired the expressive power of “those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses – where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere.”

Together with others, including André Breton, Dubuffet strove to seek out and collect works of extreme individuality and inventiveness by creators who were not only untrained artists but often had little concept of an art gallery or even any other forms of art other than their own.

The term Outsider Art was coined by art critic Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English synonym for art brut . While Dubuffet’s term is quite specific, the English term Outsider Art is often applied more broadly, to include the self-taught, the Naïve, the visionary, the intuitive, the eccentric, the obsessive, the compulsive, as well as categories such as folk art, primitive art, tramp art, and prison art.

As artists and collectors have come to appreciate its many qaulities, Outsider Art has entered the mainstream in its own right. The diverse influences of many forms of Outsider Art are now apparent in the work of an increasing number of “trained ” artists who have turned their back on changing trends and fashions to try and form a truly singular reality for themselves. An annual Outsider Art Fair has taken place in New York since 1992, refelecting a growing interest in works of art emerging from the margins of culture.

Source: Wikipedia and Raw Vision.com

Echo McCallister (1945- )

Born into a large hardscrabble family in a desperately poor section of West Virginia, Echo Ray McCallister grew up with an illiterate, alcoholic and abusive father. As his sister says, McCallister was always called “Echo” – not as a nickname but as his actual given name honoring two of his uncles, Eck and Ray. This was truly fortuitous and mythically propitious since although he was mostly silent and secretive, Echo would at times speak, but (as it is said) only compulsively and reflectively “to repeat the last word said to him.”

Although mostly silent, Echo was always drawing- always soundlessly saying, or trying to say, something. It’s just that no one cared enough to look or listen. It was more convenient to have him silently withdraw into the hollowed out caverns of his mind. These were places that did not invite company, and no one in McCallister’s early years seemed to notice his special language of images. As is often the case for those diagnosed with autism, visual expression for McCallister took precedence over verbal communication. Moreover, because of his disabled condition and the progressively intense neglect of his father, McCallister had to contend with various periods of hospitalization in state psychiatric wards while growing up, a situation that became permanent and frightening after the death of his mother and after his older sister was no longer able to care for him.

Redemptive recognition eventually came in the form of a young staff person, Tim Urbanic, who was hired at Spencer State Hospital to establish an art therapy program. It was Urbanic who discovered Echo McCallister’s amazing multi-dimensional pictures and brought them to the attention of a larger audience. Urbanic recounts the first time he saw Echo drawing:

“He was drawing on a postcard sized piece of paper, 3” x 4”. He was drawing a house, but what was so unusual was that what he had shown was more than three-dimensional. I would say that it was four-dimensional or maybe in the fifth dimension. That means not only did we see it in three dimensions in the art sense, but we were seeing the inside of the house, every single nail that it took to hold every board together, every light bulb, every switch. Everything was in this picture, in this tiny piece of paper.”

Urbanic’s actions eventually led to McCallister’s first public art exhibition in Washington DC during the early 1990s. Now McCallister lives in a halfway house and, although he is mostly oblivious to his reputation as an artist, he continues the healing work of drawing his remarkably captivating images.

Source: “Echos from Hollow Places: The Art of Echo Ray McCallister by N.J. Girardot, Lehigh University Distinguished Professor of Comparative Religion, in Echo McCallister: The Silent Outsider, published by NAEMI (National Art Exhibitions by the Mentally Ill).

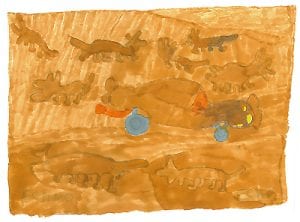

Charley Kinney (1906-1991)

Artist brothers, Charley and Noah Kinney were born six years apart—1906 and 1912 respectively—into a life of subsistence farming not so far removed from that eked out by the earliest white settlers in a remote area of Northeast Kentucky, called Toller Hollow.

Their lives spanned a tumultuous era in history, a time of unprecedented economic, technological, socio-political and cultural change. Many of these developments disrupted and made an anachronism of the way of life and world view the Kinney brothers had inherited from their parents.

Charley was a natural storyteller and he did so through his drawings, watercolors and fiddle playing. In 1970, he began painting seriously, executing several hundred pieces over the next twenty years. Dramatic portrayals of natural and supernatural forces fill his narratives, populated by “haints” (ghosts), butchering, Biblical scenes, and everyday events of the Appalachian mountain people. Correct scale and proportion were of little interest. Necessary frugality defines the brothers’ work: old window shades became paintings, and creek clay was formed into animal and human-shaped sculptures. Found materials were recycled into art works which now reside in many private and museum collections, including the Kentucky Folk Art Center (KFAC) at Morehead State University.

“The Kinney brothers are the stuff from which myths and legends so easily arise,” said Adria Swain, KFAC curator. “As artists and musicians, Charley and Noah were local standard bearers of their culture, and of a way of life that they adhered to long after most others had abandoned it for generic late 20th century America. All that discussion notwithstanding, the art is powerful; it stirs your gut.”

Lee Kogan, of the American Folk Art Museum, New York writes, “While a personal vision and a sense of place shaped the awareness and identity of each of them, [The Kinneys’ art] transcends each one’s personal history, communicating universal human values. One cannot help but react to [their] self sufficiency, ingenuity, humor, sense of community, wisdom, imagination, and talent, all put to good use. Their uniquely expressed artworks, including several 20th century masterpieces, offer relevant messages for a local, regional, national and global audience.”

The brothers died within six months of each other in 1991.

SOURCE:The Kentucky Folk Art Center, a cultural, educational and economic development service of Morehead State Universi

ty.

Purvis Young (1943- )

Art critics have attempted to place Purvis Young in a variety of established art movements: expressionism, folk art, outsider art, arte povera, and urban art.

In 1972, after learning of the “Freedom Walls” created by artists in Detroit and Chicago, Purvis Young decided to create his own public mural in Overtown, Miami’s inner-city– coined “Good Bread Alley.” The installation was visible from the newly constructed Interstate 95, which had all but dissected and consequently isolated the once prosperous black community– in which Purvis was born and raised– from the rest of South Florida. Once billed as the “Harlem of the South”, it became populated by crack-heads, their dealers, prostitutes and pimps.

Young filled the mural with images protesting war, poverty and racial indifference.

“It was two stories high, nothing but artwork,” Young says. He would sell individual panels to fascinated tourists. Now his paintings hang in more than fifty museums nation wide.

Representing Young’s unique view on life is a symbolic vocabulary where city street scenes move to the rhythm of life, wild horses roam free, “eyes of establishment” loom from above, ancient warriors do battle, immigrant-laden boats set sail, legendary jazz and blues performers rip. It is here that Purvis Young easily, yet effectively, expresses his true feelings.

Because he could never afford canvas, Purvis paints on every surface available to him – discarded plywood and cardboard, refrigerator doors, table tops, scraps of fabric and metal trays, often brought to him by scavengers in his neighborhood. Purvis Young has been creatively “recycling “ long before it was either fashionable or profitable.

Source: Daniel Aubry gallery, NY and Shawn Bean, writing for Florida International Magazine, October 2006.

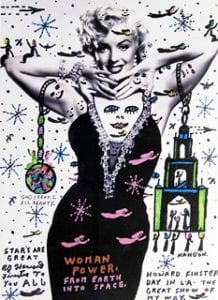

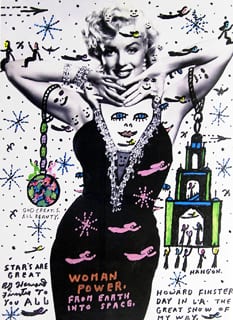

Howard Finster (1916-2001)

A self-proclaimed “Man of Visions,” Howard Finster was one of America’s most widely known and prolific self-taught artists, producing over 46,000 pieces of art before his death in 2001.

Born in rural Alabama in 1916, Finster went on to become a preacher, tent revivalist, and “master of 22 different trades” before building his roadside tribute to inventors, the Plant Farm Museum. Later dubbed “Paradise Garden” by Esquire magazine, this rock- and junk-encrusted wonderland was the focus of Finster’s life work. In 1976, however, this focus shifted slightly. As he was using his hands to apply paint to a refurbished bicycle, Finster noticed that the paint smudge on his finger had created a perfect human face. A voice spoke to him, saying, “paint sacred art.” In response, Finster churned out thousands of sermon-laden artworks with subjects ranging from historical characters and popular culture icons like Elvis Presley to evangelistic fantasy landscapes and futuristic cities. Most works are meticulously covered in Finster’s own hand-lettered words and biblical verse, recording visionary prophesies and providing glimpses of a celestial outer space world that Finster believed God had revealed to him.

Finster’s preaching experience and showman-like personality helped shape his public persona and ever-increasing celebrity. To spread his vision beyond Paradise Garden, Finster designed record album covers for rock groups such as R.E.M. and Talking Heads. Interviews, films, and his famous appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson further advanced his evangelical message.

The industry of promotion and production that surrounded Finster’s name ended up defining his final years. Though he continued to create many fine works, some critics felt that the quality of his work suffered. However, Finster’s intentions remained true to his inner voice—to make sacred art. Well-known and misunderstood, his position remains polarized, suspended somewhere between awe for his tireless, faith driven creativity and reluctance by the art community to accept his place in the pantheon of contemporary art.

Thanks to a gift from the Thomas E. Scanlin collection in 2004, Lehigh University now possesses one of the largest collections of works by Howard Finster in the world.

Two Finster works, The Way of Jesus and Love and Kindness (Garden Sign), part of the LUAG Teaching Collection, are currently on loan to a major retrospective exhibition Stranger in Paradise: The Works of Reverend Howard Finster organized by the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The exhibition will travel to the Chicago Cultural Center (Chicago), The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University (Alabama), the Museum of Contemporary Art, Jacksonville (Florida), and the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville (Tennessee).

The exhibition is accompanied by a 152-page hardcover, full color catalogue and includes essays by N. J. Girardot (Lehigh University Distinguished Professor of Comparative Religion), Jim Arient, Phyllis Kind, and exhibition curator Glen C. Davies.

SOURCE: Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.