- This event has passed.

Santiago Calatrava: Early Drawings, 1980-82

September 13, 2006 - December 17, 2006

Fourteen original sketches by the visionary award-wining architect, artist, engineer, and sculptor. Internationally renowned for his dramatic designs in Europe, major projects include expansion of the Milwaukee Art Museum and the new World Trade Center Transportation Hub in New York.

A group of early sketches by Santiago Calatrava, by Tom F. Peters

We admire the mature works of master builders, but rarely do we examine the influences that formed them. Almost all the drawings exhibited here were given to the collector on the same day and therefore form a unit. They freeze a moment in the development of a creative designer and provide insight into the thoughts and models that made Santiago Calatrava the fascinating designer he has become. Although this is a small group of sketches, the collection is rich in association. It shows how Calatrava absorbed and transformed some of the many influences that helped him create his own way of seeing the world.

Calatrava was born in Spain in 1951 and educated as an architect in Valencia. While he was completing his studies, he discovered that he knew too little about structure and construction and cast about for a master engineer from whom he could learn what he lacked. The great masters in his own culture, Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) and Eduardo Torroja (1899-1961) were dead, but the young architecture student had already been attracted to Swiss engineering and in particular to the work of Robert Maillart (1872-1940). Maillart’s innovative concrete bridges had been publicized in the writings of Max Bill (1908-1994) and Sigfried Giedion (1883-1968) He therefore decided to pursue his studies in civil engineering at the ETH – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology – in Zurich, especially under the tutelage of the celebrated bridge builder Christian Menn. (b.1927) Menn considers himself a disciple of Maillart although they never met and he was only a boy when the master died. Menn was intrigued by the fiery young Catalan who stormed his office politely demanding to be taught. Calatrava became Menn’s enthusiastic student, and thereby an heir to a century of innovative tradition in Swiss structural engineering. That is the background on which these sketches can be read.

Most of the exhibited sketches concern a project that preoccupied Menn in the late 1970s: the Ganter Bridge on the Simplon Pass road in the Swiss Canton of Valais. The professional and academic world was fascinated with the innovative suspended box-girder in concrete. At the time Calatrava was completing his last semester with Menn , and being an architect as well as an engineer, began to experiment with the forms his professor had designed. Although he did not voice his opinion out loud, he discerned more potential in the new idea than Menn had realized, and he sketched a series of variants, some simple and some fantastic to prove his point. Calatrava showed these to his mentor, who was intrigued.

That year the International Association of Bridge and Structural Engineers celebrated its 50th anniversary with two events, a symposium in Zurich in the fall of 1979 and an international congress in Vienna the following spring. Menn gave a talk on his new bridge at the symposium to a packed audience. In the back of the hall stood the students, assistants, and lecturers of the ETH, Calatrava among them, together with a few celebrated professionals. All were enthusiastic about the project, when surprisingly Menn paused to tell the audience that a ‘young architect’ had played with his idea and come up with series of interesting variants that he wanted to share with his listeners. He then proceeded to project slides of Calatrava’s sketches to the astonishment of the audience.

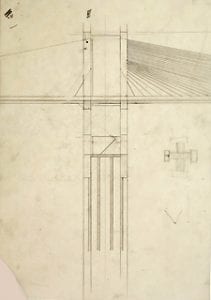

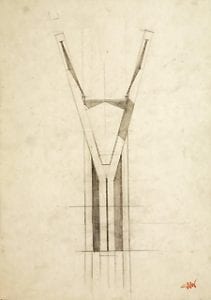

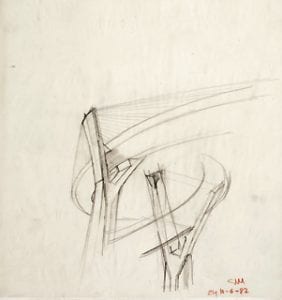

These exhibited sketches were dated on the days they were given as gifts, but their genesis lies earlier, in 1979. They are all of course influenced by Menn’s design, but are by no means mere derivations. They transcend the model to explore form in the structural idea.. In this they hark back to Menn’s own model, Maillart, who was always very concerned with the formal implications of his structures. The small Calatrava sketch of Maillart’s celebrated, three-dimensionally curved Schwandbach Bridge of 1933 in this collection demonstrates the connection poignantly, especially when we note how closely related it is to Calatrava’s own two ‘dancing heads’ of a Ganter-type bridge. But beyond the Swiss lineage, these ‘dancing heads’ also recall a late Gothic sculpture, a fantastically twisted figura serpentinata like those of Veit Stoss, (1445-1533) or perhaps more appropriately, they presage Calatrava’s own Turning Torso Building of 2005 in Malmö.

The second perspective sketch of a curved Ganter-type pier head in this collection is a reworked tracing from one of the ‘dancing heads.’ It shows Calatrava’s concern with the way a viewer understands how the structure carries its loads – a concern that again links him closely to Maillart – and the small section and elevation are further elaborations of these thoughts. Together with the two full-sized piers and the three-pier bridge proposal, the series demonstrates the subtlety with which Calatrava develops and elaborates his ideas. A careful analysis of these drawings and of a third, full-size pier sketch (now in The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities

in Santa Monica) steps outside the scope of this essay, but it could tell us much about Calatrava’s early thinking and his design process.

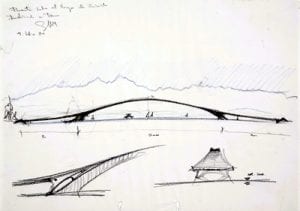

Apart from the Ganter variants, the collection also includes several designs that indicate the direction Calatrava’s career would take. The 1980 ‘Puente sobre el lago de Zurich’, perhaps his earliest documented independent design, came about during a coffee break at the ETH. The city of Zurich had announced a competition for the restoration or replacement of the old Limmat Bridge over the mouth of the river at the lake. We lecturers were sure that it would be restored, as the municipal government was far too conservative and timid, we felt, to dare anything new. Calatrava came to the table where we were hotly debating the pros and cons of a new structure. He had his ubiquitous sketchpad with him and tossed off the drawing, remarking that what the city needed was a high arch, a strong statement that would frame the view of the Alps at the end of the lake, not a beam to bar the scene. He avidly disagreed then, as he still does, with the competition requirement that the ‘structure fit into the landscape.’

The structural aspects of this sketch are equally telling. Since the river banks are soft and cannot take the thrust of a 300-meter arch, Calatrava proposed a tension band of concrete fixed above the arch footing, in order to pull some of the thrust beyond and anchor it in more solid ground. How this might have worked is unclear, but even at that early period he had a sharp eye for the essence of a design problem and for its technical implications. Faint blue lines show how he proposed to cantilever the arch from both banks using temporary towers with tie-backs like those that the English engineer Thomas Telford (1757-1834) proposed in 1816. Calatrava’s early love of construction history and his ability to use force diagrams in developing form are continuing themes in his work.

The proposal was quickly done and yet, like the sketch of a dove also in this collection, it clearly shows another aspect of the designer: the beginnings of Calatrava’s hallmark fascination with the relationship between anatomy and engineering structure. In these two sketches Calatrava translates Matisse’s and especially his compatriot Picasso’s concerns with line, volume, mass, and body into engineering terms. Where the dove directly documents Calatrava’s connection to Matisse and Picasso, the Zurich bridge illustrates once again his drive to translate influences on his terms into his own way of seeing things.

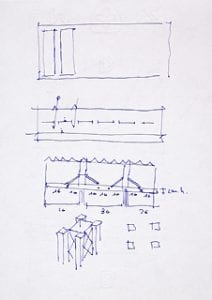

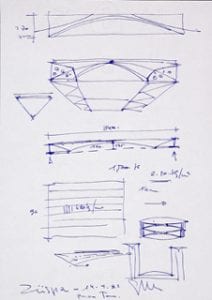

One might easily overlook the double-sided pen-and-ink drawing of the design he intended to submit for the competition for the design of a new hall for the Züspa exhibition in Zurich. Executed and dated 1981, it is somewhat later, and prima vista less visually attractive than the post-dated Ganter Bridge variants. This little drawing was done as an explanation of his intentions rather than a design exploration, but even there Calatrava was unable merely to explain. The sketches for the three-dimensional roof girders on the recto begin as an explanation, but immediately digress into variants that predate the similar roof for the Jakem Warehouse in Münchwilen 1983-84. We are privileged here to look over his shoulder as he invents a new form.

There are more facets to Calatrava’s talent, many more than one can demonstrate in the sketches in this collection. Simple, few, and early they may be, but they provide an intimate glimpse into the fertile mind of one of the truly fascinating engineering and architectural designers of our time.

-Tom F. Peters

06 June 2006

LECTURE: Tom Peters: “Santiago Calatrava”: Fall 2006

LECTURE: Tony Viscardi: “Architecture and the Body”: Spring 2006

VIDEO: Santiago Calatrava: “In the News” : Fall 2006