By Mary C. Foltz, Associate Professor of English, Lehigh University

July 31, 2021

Although most will be aware of the literary influences on Naylor’s second novel, some readers may be surprised to learn about its engagement with Black intellectual history. The archive includes a typed bibliography that Naylor compiled during the time when she wrote Linden Hills, which focuses primarily on historical and sociological texts that explore the Black middle class. Previous scholarship on Naylor’s Linden Hills celebrates a wide variety of literary texts that inspired her (re)visionary work with Dante’s Inferno. While some articles address how she “adopts,” “revises” or “subverts” Dante’s work to create her affluent neighborhood, others trace influences from classical texts like Virgil’s Aeneid, early modern drama such as Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, and gothic fiction. Exploring how Linden Hills engages with mid-twentieth-century intellectual history enhances these rich critical conversations that have focused on Naylor’s engagement with literary texts.

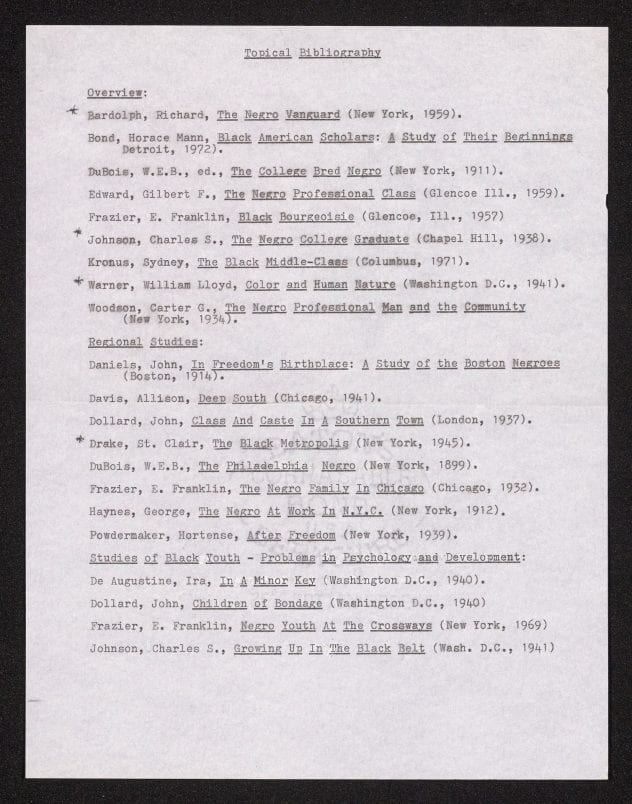

The two boxes of material from the Linden Hills period contain moving diary entries about her writing process and travel, drafts of manuscripts, and her research materials, including the aforementioned typed “Topical Bibliography” that lists texts that she referenced in preparation for or as she wrote her second novel (see Image 1). A few of these texts make it into the description of one character’s (Braithwaite’s) library in her novel. Compiling bibliographies seems to be standard practice for Naylor during the height of her career, as the archive also includes similar typed bibliographies for the Mama Day and Bailey’s Café periods. Near the “Topical Bibliography” in the Linden Hills materials, Naylor also included a handwritten document, listing magazines and other books that she was thinking about as she worked on the novel (see image 2). Although the archive does not reveal the extent to which Naylor referenced materials listed on her bibliography, it does give insight about specific works that may have influenced her work on Linden Hills, and it provides information about the intellectual contexts that informed her writing.

Works cited on these documents position Linden Hills not only as an intervention into the capitalist financial imaginary of the 1980s, but also into the Black patriarchal intellectual tradition that explores class, poverty, and ideals about social mobility based on hard work and merit. The “overview” section of the typed bibliography lists nine separate works, including monographs by mid-century academics like E. Franklin Frazier, renowned intellectual patriarchs such as W.E.B. Du Bois, and lesser-known figures like Richard Bardolph. Most of the books in this section theorize the successes of the Black middle class and its position in the U.S. economy. Some of the bibliographic works remain highly critical of narratives about the Black middle class, especially as they are used to bolster national narratives about social mobility and to obscure the economic effects of racism. Others celebrate members of the Black middle class as models of class mobility despite acknowledging the continued threat of institutionalized racism to economic ascent. In Linden Hills, Naylor aligns herself with criticism of the idea that a wealthy elite will be the vanguard for improving the lives of marginalized urban Black communities. Further, as a corrective to texts written by men and focused primarily on Black men in the middle class, Naylor’s novel provides a Black feminist vision of how capitalist notions of subjects’ value are grounded in racialized and gendered understandings of labor, how competition among laborers distorts subjects’ relationships to self and others, and how a focus on the financial successes of an elite group undermines structural critique of economic systems that disenfranchise larger Black communities. A closer look at one text from the bibliography illuminates the novel’s intervention into scholarly conversations about the Black middle class.

The first text listed on Naylor’s bibliography for Linden Hills is Richard Bardolph’s The Negro Vanguard (1959), which counters white supremacist history by profiling hundreds of African Americans who made an impact in their fields and in U.S. history. Throughout his work, Bardolph emphasizes the betrayal of democracy and achievement society by slavery, Jim Crow laws, and enforced segregation; he further posits a progressive movement by which the African American vanguard has built successful businesses, religious institutions, and colleges as they navigated racism. For Bardolph, economic institutions should push back against discrimination in order to give each citizen the opportunity to succeed based on merit and work ethic. Rather than understanding U.S. capitalism as an economic system that depends on the exploitation of devalued groups of people, including racialized others, he looks forward to a late-20th-century moment when all will be free to compete against each other to become elite Americans. For him, status “determined by achievement” is central to U.S. national values, and the fact that African American communities have had to build their own institutions in response to racist segregation shows that this quintessentially American value has not yet been realized. Bardolph celebrates the African American vanguard for building economic opportunity where a white supremacist state failed, as “by their courage and their faith, their strength and their skills, … [they opened] doors where the millions may follow” (Bardolph 462).

Linden Hills critiques Bardolph’s faith in capitalism as a great equalizer. Instead, it links the historical exploitation of enslaved Black laborers to the continued exploitation of Black working-class populations, including Black women who perform devalued domestic labor. The novel’s history of the first Luther Nedeed refuses a celebratory take on the vanguard, by presenting a fictional figure who may have garnered wealth through the sale of his first wife. Because he purchases a wife (Luwanna Packerville) after moving North, it is clear that he has benefited, albeit in a smaller way than wealthy white families, from slavery. Further, he makes money off of the two things that people had to do—“live and die”—by becoming a landlord and working in the mortuary business. By beginning the novel with a character who makes money off Black working-class laborers in life and death and who benefits from the unpaid labor of an enslaved wife, Naylor’s portrayal of the vanguard foregrounds the exploitation that enables economic gain and physical comfort. To be fair, Bardolph profiles many in the vanguard who fought against slavery, prejudice, and/or Jim Crow Laws, including Gabriel Prosser, James Forten, James Madison Bell, Fredrick Douglass, and W.E.B. DuBois; like Naylor, he centers those who have been left out of larger national narratives, and he does include women in his study. Still, Naylor’s counter-history of the vanguard invites us to think about who is left out of celebratory narratives of Black excellence in achievement society. Linden Hills addresses this question with narratives about Black women working in the home and working-class Black people (Willie, Norman, and Ruth) who are critical of residents of the affluent enclave. Naylor’s genealogical account of the Nedeed patriarchs challenges the celebration of monied individuals by attending to the people exploited in capitalist economies and by showing how wealth is accrued from “surplus” income channeled to managing and ruling classes.

Just as the founding Nedeed patriarch made money off working-class Black populations, many of the people living in the affluent Linden Hills benefit from corporations that pay low wages. Maxwell Smyth, for example, is an executive at General Motors, and his own extravagant wages depend upon keeping labor costs low, as most readers in the 80s would know from memories of the United Auto Workers’ sixty-seven day GM strike in 1970. Naylor’s portrayal of Smyth again reveals her interest in the costs of celebrating those who “rise to the top” rather than the workers who make collective contributions. Additionally, through characters like Smyth, Naylor also shows how social mobility can pit affluent Black leaders against working-class people. Some residents of Linden Hills loathe the neighboring Black community, Putney Wayne, because that community includes impoverished and devalued Black people, with whom those in Linden Hills do not want to be associated. “Achievement society,” as Bardolph calls it, grants residents of Linden Hills a sense of superiority over residents of Putney Wayne, and the novel thus challenges Bardolph’s vision of the uplift brought about by the vanguard for all African American people.

The Nedeed family genealogy also critiques Black patriarchal histories like Bardolph’s that do not substantially address the intersecting impacts of sexism, racism, and classism in Black women’s lives and continue to sideline Black women in historical accounts of leadership and achievement. As Naylor’s aesthetic focus in The Women of Brewster Place and Bailey’s Café has been on “common,” working-class, and still exceptional Black women, she challenges historical accounts, like Bardolph’s, that ignore the contributions of working people, especially Black women working in devalued forms of labor. In Linden Hills, we can read Willa’s work in the basement of the Nedeed home in light of Bardolph’s monograph as she offers moving traces of valuable and innovative Black mothers and homemakers absent from histories of the vanguard. As Lester and Willie move closer to Willa’s basement prison, they are creeping toward a hidden history of exploited women that challenges the fantasy of an achievement society and the myth of a capitalist system where all are rewarded based on talent and effort. Indeed, the hard work of the Nedeed wives is neither rewarded nor recorded in the history of the family, but rather shuttled off to mold in the basement.

To conclude, Naylor shares with Bardolph an emphasis on uncovering histories of Black individuals and communities left out of hegemonic accounts of the nation as well as an interest in how to address racial capitalism, which limits the economic possibilities for Black communities and individuals. However, her novel takes aim at Black patriarchal histories of achievement that ignore the contributions and full valuable humanity of Black working-class people and Black women specifically. Finally, Naylor also targets capitalist ideologies that promote fantasies of “fair” competition between individuals in the labor market. Her novel shows that capitalism depends upon devaluing specific forms of labor and marginalized populations to justify low wages for some and higher wages for those whose labor is deemed more important. For her, studies of history that trace racial capitalism call for widespread condemnation of economic systems that depend upon the exploitation of laborers.

Although I only address Bardolph here, other texts in Naylor’s bibliography can also enrich our understanding of how her novel intervenes into mid-century intellectual history, especially historical and sociological studies of the Black middle class. Other bibliographies from the archive show that many of Naylor’s novels engage with a wide range of academic texts. For example, her bibliography for Bailey’s Café includes a variety of feminist academic publications about sex work and studies of Indigenous conceptualizations of two-spirit people. Overall, attention to Naylor’s bibliographies can give readers greater insight into the research that sparked her interest as she crafted each literary work. For scholars, her bibliographies reveal how her novels engage and contribute to twentieth-century intellectual history.