Film Deets:

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Screenplay: Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams

Actress: Elizabeth Taylor

Category: Coded Queerness

Themes: Queer Monsters, Child Abuse

Why do these screams matter?

Queerness takes on a decidedly unsympathetic deviance in Tennessee Williams’ Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). Unlike the author’s other coded film adaptations of the 1950s, A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), the film leans into its queer content and grapples more openly with cultural taboos (Pugh 22). The film revolves around Catherine (Elizabeth Taylor), a woman institutionalized after the death of her cousin, Sebastian, who died under mysterious circumstances while with her on holiday. Sebastian’s mother, Violet (Katherine Hepburn), wants a lobotomy performed on Catherine but it remains to be seen what Violet’s motivations are for demanding the procedure.

Released when the Hays Code was softening its stance on depictions of queerness in film, – indeed, movies depicting homosexuality were approved by the PCA provided the scenes were handled “with care, discretion, and with restraint- Suddenly, Last Summer nevertheless ignited the ire of The National Legion of Decency for its themes of cannibalism, sexual violence and moral corruption (Hadleigh 27; “Legion Labels Film” 36). Embedded within the film is a portrait of queerness as predatory and wholly destructive that plays into the era’s obsession with rooting out queerness and pathologizing LGBTQ+ identity as a mental disorder (Creadick 93). For Sebastian, his entire story is bound up in the silence of the closet. Because he is never given space to speak for himself, and the audience only comes to understand him through the memories of others, Sebastian’s monstrosity, like his sexuality, is demonized and yet, largely invisible.

Released when the Hays Code was softening its stance on depictions of queerness in film, – indeed, movies depicting homosexuality were approved by the PCA provided the scenes were handled “with care, discretion, and with restraint- Suddenly, Last Summer nevertheless ignited the ire of The National Legion of Decency for its themes of cannibalism, sexual violence and moral corruption (Hadleigh 27; “Legion Labels Film” 36). Embedded within the film is a portrait of queerness as predatory and wholly destructive that plays into the era’s obsession with rooting out queerness and pathologizing LGBTQ+ identity as a mental disorder (Creadick 93). For Sebastian, his entire story is bound up in the silence of the closet. Because he is never given space to speak for himself, and the audience only comes to understand him through the memories of others, Sebastian’s monstrosity, like his sexuality, is demonized and yet, largely invisible.

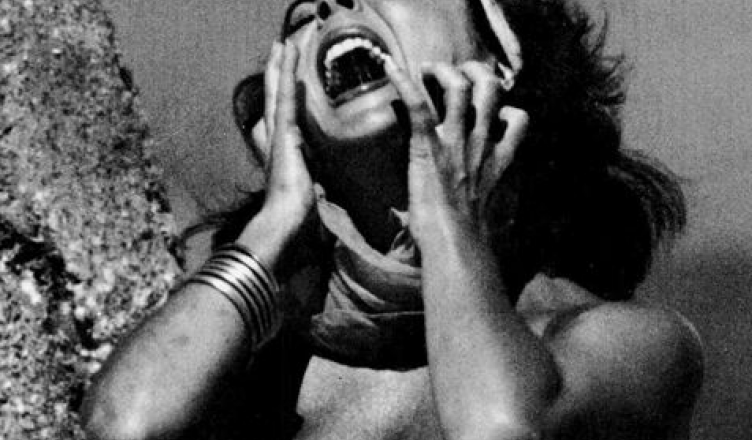

Who is allowed to hold cultural power comes into play in our first scream in which Catherine is told by her mother (Mercedes McCambridge) and her brother (Gary Raymond) that they intend to permit the doctors to move ahead with Catherine’s lobotomy. They’ve agreed to do so at the behest of Violet, who is blocking the family’s access to their inheritance from Sebastian until the paperwork is signed. Realizing that she is in imminent danger, Catherine escapes her private room and runs through the asylum where she winds up on a ledge overlooking a room of male patients. When they notice her, the room erupts into pandemonium with many of the patients grabbing at and molesting Catherine.

Catherine’s screams in this scene are essentially laying the groundwork for the film’s overall message that connects mental illness with violence. Her screams are a direct response to the threat of literally being surrounded by mental instability; an instability that becomes tangible once the men begin grabbing and fondling her. In this moment, the film is carefully distinguishing between people who are presumed to have a mental illness but who do not, like Catherine, and those who do, like the male patients. This distinction is important because of how it ultimately plays into the framing of Sebastian as the film’s monster.

As the de facto heroine of the film, Catherine’s screams and limited agency create a sympathy for the character that becomes essential in the latter half of the film for contextualizing Sebastian’s villainy when the full extent of his actions become known to the audience. Here, her screams establish her vulnerability as a woman who is threatened both by family members wanting to foist a questionably necessary medical procedure on her and by a medical establishment that equates psychological trauma with psychosis. Having witnessed Sebastian’s gruesome murder, Catherine is understandably traumatized and emotional. And yet, it is not her mental state that is fueling Violet’s insistence that Catherine receive a lobotomy but the truth about Sebastian that resides in Catherine’s troubled mind threatening to be revealed.

While the film’s depictions of mental illness are gut turning, they are in keeping with cultural attitudes of the era. This was not a time when ethics review boards examined research protocols for human rights violations. Patients whose files included notations of mental illness were routinely subjected to “treatments” that would be defined as barbaric by today’s standards (Shorter and Healy 144). Public understanding of mental illness was limited, at best, and often was described in terms that provoked fear (Parcesepe and Cabassa 2). It was also the period in which professional literature actively sought to define homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder, a movement that became institutionalized when, in April 1952, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance (a term generally used to describe people who show no regard for right or wrong) (Drescher 569). This image of homosexuality as an immoral threat was also conveyed to the public in 1953 via President Eisenhower’s executive order banning homosexuals from working for the federal government because of security risk concerns (Blakemore). And so, for original audiences of Suddenly, Last Summer, there was already an expectation of a link between homosexuality and threatening behavior that the film could capitalize on in framing its monster.

While the film’s depictions of mental illness are gut turning, they are in keeping with cultural attitudes of the era. This was not a time when ethics review boards examined research protocols for human rights violations. Patients whose files included notations of mental illness were routinely subjected to “treatments” that would be defined as barbaric by today’s standards (Shorter and Healy 144). Public understanding of mental illness was limited, at best, and often was described in terms that provoked fear (Parcesepe and Cabassa 2). It was also the period in which professional literature actively sought to define homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder, a movement that became institutionalized when, in April 1952, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance (a term generally used to describe people who show no regard for right or wrong) (Drescher 569). This image of homosexuality as an immoral threat was also conveyed to the public in 1953 via President Eisenhower’s executive order banning homosexuals from working for the federal government because of security risk concerns (Blakemore). And so, for original audiences of Suddenly, Last Summer, there was already an expectation of a link between homosexuality and threatening behavior that the film could capitalize on in framing its monster.

It is that link that fuels our next scream. Here, Catherine is flooded with memories of the day Sebastian was killed. As her memory returns, so too does her horror at what transpired on that fateful day.

For the entirety of the film, Sebastian is coded as queer. He is interested in art and is a poet, he has an unnaturally close relationship with his mother, and he is described multiple times as being sensitive and fastidious-all codes for queerness in the 1950s (Mislak). Sebastian’s story is also told exclusively through the memories of two women, and that framing emphasizes that Sebastian wasn’t a “man’s man” but a man surrounded by women in whom he had no sexual interest. The icy aloofness of Violet, when set against Catherine’s anguished scream here further reiterates that Sebastian was raised in privilege and that access to power when coupled with his homosexuality is intended to increase the audience’s understanding of Sebastian’s monstrosity. Because what would be worse in the minds of the era’s audiences than a homosexual? A homosexual with the means to allow him to act with impunity.

Once the flood gates open for Catherine, she not only remembers the spectacle of Sebastian’s death but also the circumstances that led to it.

What’s especially clever about this scene is the way that it inverts the earlier moment of Catherine being groped by the asylum patients. Whereas we are positioned to sympathize with Catherine’s plight of being attacked by mentally ill people in the earlier scene, here we are meant to read Sebastian as deserving of his death due to his mental illness, i.e., his homosexuality. Lest we question that Sebastian is supposed to be the monster of the film, the movie provides an explicit homage to another horror classic. The documentary The Celluloid Closet, which looked at depictions of homosexuality in film, notes that the scene of Sebastian ascending the hill while being chased by a mob echoes strongly the scene of the Creature in Frankenstein being chased by torch-carrying townspeople. The fact that we never see Sebastian’s face, moreover, not only echoes the queer invisibility of the era but reinforces the idea that homosexuals aren’t actual, complete people. Rather, they are simply the incarnation of their sexual desires.

Violet’s reaction to Catherine’s memories also work to silence Sebastian within the text. Throughout the film, Sebastian’s “unnaturally close” relationship with his mother is framed as abnormal and potentially the reason for Sebastian’s monstrosity, reflecting the era’s belief that mothering choices could create children with queer identities (van den Oever 1). In his article “Blond Ambition: Tennessee Williams’s Homographesis,” Stephen Bruhm explains how the specter of queerness in the 1950’s was frequently tied to mother-blaming:

Without saying so, Williams draws a textbook study of the kind of homosexual man the Freudian enterprise had identified some forty-five years earlier, the type whose delusions of grandeur result from an inability to cast the mother in the role of sexual otherness, and who instead identifies with her too fully. In the desire to please her, he identifies with her desire, the desire for the male body, for the phallus of another man” (98)

Shattered by the exposing of Sebastian’s true identity to the world, Violet reiterates her demand that the doctor “Cut that story out of her [Catherine] brain.” Her demands intersect with Catherine’s screams of horror creating a compelling understanding of Sebastian’s monstrosity. The narrative power to define Sebastian and his “appetites” remains with the two women, silencing Sebastian and removing his autonomy.

Shattered by the exposing of Sebastian’s true identity to the world, Violet reiterates her demand that the doctor “Cut that story out of her [Catherine] brain.” Her demands intersect with Catherine’s screams of horror creating a compelling understanding of Sebastian’s monstrosity. The narrative power to define Sebastian and his “appetites” remains with the two women, silencing Sebastian and removing his autonomy.

The scene is also deeply, deeply troubling for the way it perpetuates one of the most harmful stereotypes associated with queerness: the gay pedophile. The crowd chasing Sebastian is composed of young men and boys whose vicious attack is implied to be a response to Sebastian’s abuse. When Catherine reveals that she and Sebastian would travel to foreign countries so that she could “procure” for him, it’s clear that Sebastian is using his wealth and privilege in extremely damaging ways. And the visual representation of these young men and boys of color from impoverished backgrounds makes it clear that Sebastian was specifically targeting those already vulnerable. Catherine’s scream here functions as a tacit acknowledgment of Sebastian’s perversion that exculpates Catherine from the responsibility for his death but it is also a visceral reckoning of her culpability in enabling Sebastian’s violence for so long.

Works Cited

Blakemore, Erin. “How LGBT Civil Servants Became Public Enemy No. 1 in the 1950s.” History, 10 October 2019.

Bruhm, Steven. “Blond Ambition: Tennessee Williams’s Homographesis.” Essays in Theatre, vol. 14, 1996, pp. 97–105.

Creadick, Anna G. Perfectly Average : The Pursuit of Normality in Postwar America. University of Massachusetts Press, 2010.

Drescher, Jack. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 5, no. 4, Dec. 2015, pp. 565–575.

Hadleigh, Boze. The Lavender Screen: The Gay and Lesbian Films–Their Stars, Makers, Characters, and Critics. Citadel, 2001.

“Legion Labels Film: Suddenly Last Summer Is ‘Separately Classified.’” New York Times, 4 December 1959, p. 36.

Mislak, Makayla. “From Sissies to Secrecy: The Evolution of the Hays Code Queer.” Filmic, Apr. 2015.

Parcesepe, Angela, and Leopoldo Cabassa. “Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review.” Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, vol. 40, no. 5, Sept. 2013, pp. 384–399.

Pugh, Tison. “Camp Cannibalism in Suddenly, Last Summer.” The Tennessee Williams Annual Review, vol. 15, 2016, pp. 21-35.

Schneiderman, Leo. “Tennessee Williams: The Incest-Motif and Fictional Love Relationships.” Psychoanalytic Review, vol. 73, no. 1, 1986, pp. 97–110.

Shorter, Edward, and David Healy. Shock Therapy: A History of Electroconvulsive Treatment in Mental Illness. Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Suddenly, Last Summer. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, performances by Katherine Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, and Montgomery Clift, Columbia Pictures, 1959.

The Celluloid Closet. Directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, performances by Lily Tomlin, Quentin Crisp, and Whoopie Goldberg, Sony Picture Classics, 1996.

van den Oever, Roel. Mama’s Boy: Momism and Homophobia in Postwar American Culture. Springer, 2012.