Film Deets:

Director: Robert Aldrich

Screenplay: Henry Farrell, Lukas Heller

Actresses: Bette Davis, Joan Crawford

Category: Hagsploitation

Themes: Disability, Caregiving, Mental Illness

Why does this scream matter?

Arguably the most famous example of hagsploitation, Robert Aldrich’s film Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? remains a divisive film among critics due to its positioning of aging women as mentally unstable menaces. The film follows the lives of two sisters, Jane (Bette Davis), a former child star, and Blanche (Joan Crawford), a woman with an undisclosed disability whose movement is encumbered by paralysis. Based on the novel by Henry Farrell, the film is a potent blend of camp, classic horror, and Grand Guignol aided by controversial flourishes of spectacle, most obvious in Jane’s appearance. Favoring the childhood dresses and hairstyle of her youth, Jane is clearly a woman caught in a suspended state of adolescence, a position increasingly at war with her adult responsibilities as her sister’s primary caregiver. As Jane’s tentative grip on reality becomes more pronounced, Blanche finds herself increasingly in her sister’s crosshairs.

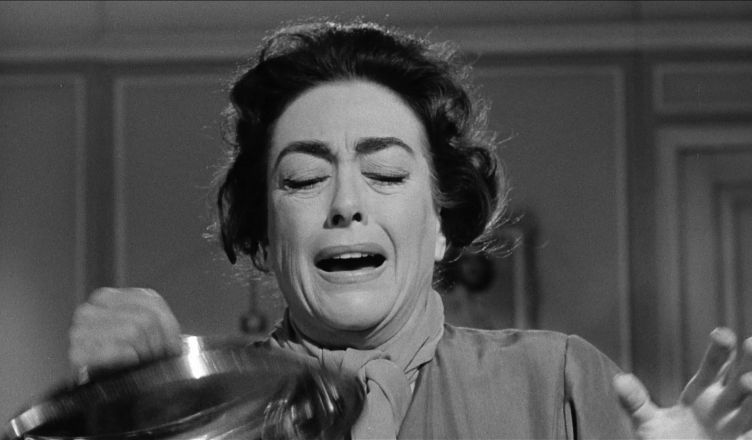

With the “horrors of aging…hyperbolically symbolized in the physicality of [Davis’] Baby Jane,” the film is frequently referenced as an example of how this subgenre exploits older women (Buchanan-King 409). Christopher Pullen, a professor of media and inclusivity, argues that “demeaning roles that conveyed problematic stereotypes about aging female bodies and the life chances that may be proffered to older women” are an essential characteristic of hagsploitation (Pullen, as quoted in Hobbs). While I appreciate his point that these films do codify negative perceptions related to the aging body, to only frame the conversations taking place in these films as exclusively simple and stereotypical does the films a great disservice and fails to consider the social-political landscape in which they emerged. In the case of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, for example, it is impossible to separate the spectacle of aging from the stressors of caregiving without the benefit of a support system. Consider this scene in which Jane serves Blanche a dead rat on a silver serving tray and how she then cackles in glee at Blanche’s escalating screams of horror.

On its face, this scene is exploiting a simple gendered stereotype. The idea that any interaction between two women will ultimately devolve into a catfight is so prevalent in our culture, particularly in the 1960s, that it is a joke that has spanned decades (Reinke 163-164). But it is a joke that is grounded in patriarchal framings of women as overly emotional and inherently jealous. Certainly, it can be argued that both of those things are true as Jane is both erratic and resentful toward her sister. But there is also a subversive commentary about the intersection of age and disability operating beneath its surface. While Blanche screams because of her mortification at seeing a dead rat on her lunch tray, her scream is also one of anguished frustration. Because Blanche is in a wheelchair and is dependent upon Jane’s assistance to perform daily self-care functions, her anger at not being able to be independent and have her own agency is building. Her scream in this moment operates as a pressure valve that allows Blanche an opportunity to access and release her rage. Blanche’s scream is a guttural one in which the reality of her situation, particularly her dependence upon her increasingly cruel caregiver, is a scathing critique of the suffering that is endured when there are no systemic safeguards to protect the needs of marginalized populations, including the elderly and disabled. And for the time period, this critique is especially concrete.

On its face, this scene is exploiting a simple gendered stereotype. The idea that any interaction between two women will ultimately devolve into a catfight is so prevalent in our culture, particularly in the 1960s, that it is a joke that has spanned decades (Reinke 163-164). But it is a joke that is grounded in patriarchal framings of women as overly emotional and inherently jealous. Certainly, it can be argued that both of those things are true as Jane is both erratic and resentful toward her sister. But there is also a subversive commentary about the intersection of age and disability operating beneath its surface. While Blanche screams because of her mortification at seeing a dead rat on her lunch tray, her scream is also one of anguished frustration. Because Blanche is in a wheelchair and is dependent upon Jane’s assistance to perform daily self-care functions, her anger at not being able to be independent and have her own agency is building. Her scream in this moment operates as a pressure valve that allows Blanche an opportunity to access and release her rage. Blanche’s scream is a guttural one in which the reality of her situation, particularly her dependence upon her increasingly cruel caregiver, is a scathing critique of the suffering that is endured when there are no systemic safeguards to protect the needs of marginalized populations, including the elderly and disabled. And for the time period, this critique is especially concrete.

In the 1960s, people with disabilities had limited protections to ensure their safety. There was no Americans with Disabilities Act, disabled children still did not have the right to a public education and the Center for Independent Living was just getting ready to open its doors (Meldon). While the decade did see a move away from institutionalizing people with disabilities, support services for caregivers were sporadic at best. Like Blanche, a person with a disability that limited independent movement had to hope that their caregiver was competent because there was simply no oversight to ensure care standards. Caregiving during the 1960s (and still now) was highly gendered (Hororwitz 551; Singer et. al. 100-101). Women were expected to provide the care and there wasn’t yet an understanding of the ways in which caregiving stress can impact physical and mental health (“Who Are Family Caregivers”). Like Jane, caregivers were often left to navigate the experience in a silo with little to no support structures to help with which to process the experience. Exacerbating caregiving expectations was one’s economic class. In 1959, the poverty rate for the elderly in the United States was a staggering 46%, a position Jane and Blanche both find themselves attempting to navigate (Morrill). For the elderly, an already disenfranchised group, being disabled was an additional layer of invisibility.

Blanche’s scream shatters that invisibility and is especially interesting for how it works in concert with Jane’s maniacal laughter. For much of the film, the audience is positioned to see Jane as the villain. But the film’s shocking revelation that Blanche became disabled while trying to kill Jane in a fit of jealousy reframes some of Jane’s motivations. Jane’s mistaken belief that she is to blame for Blanche’s suffering leads to Jane’s mental deterioration, a deterioration that is only exacerbated by the demands of being a constant caregiver. Jane’s descent into madness can be read as a statement on the pressures we put on women to be primary caregivers even when doing so is to their detriment. Blanche’s scream and its connection with Jane’s laughter not only demonstrates cyclical abuse but also demonstrates the complexity of emotions that cause women to scream in horror films.

Works Cited

Buchanan-King, Mindy. “Joan Crawford: Problematizing the (aging) female image and sexuality in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 37, no. 5, 2020, pp. 408-430.

Hobbs, Thomas. “How What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Demonised Older Women.” BBC, 3 Nov. 2022.

Horowitz, Amy. “Family Caregiving to the Frail Elderly.” Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, vol. 5, no. 1, 1985, pp. 194-246.

Meldon, Perri. “Disability History: The Disability Rights Movement.” National Park Service, n.d.

Morrill, Richard. “50 years of US Poverty: 1960-2010.” NewGeography, 19 Feb. 2015.

Reinke, Rachel. “Catfight: A Feminist Analysis.” Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, School of Languages, Cultures, and World Affairs, College of Charleston, Vol. 9, 2010, pp. 162-185, chrestomathy.cofc.edu/documents/vol9/Reinke.pdf/

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. Directed by Robert Aldrich, performances by Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, Warner Bros. Pictures, 1962.

“Who Are Family Caregivers?”. American Psychological Association, www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/faq/statistics.