Film Deets:

Director: David Lowell Rich

Screenplay: Joseph Stefano

Actresses: Eleanor Parker, Gayle Hunnicutt

Category: Hagsploitation

Themes: Disability, Caregiving

Why do these screams matter?

As in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane (1962), Eye of the Cat leverages malevolent caregivers to demonstrate how the lack of concrete social services for people with disabilities potentially places them in harm’s way. But unlike its predecessor, Eye of the Cat grants its lead character the agency to respond to the machinations of those who surround her and challenge their authority. The film follows Danny (Eleanor Parker), a wealthy, older woman with limited mobility as a result of significant lung issues. She is cared for by Luke (Tim Henry), her resentful nephew, until the arrival of Wylie (Michael Sarrazin) and Kassia (Gayle Hunnicutt), her other vagabond nephew and his girlfriend.

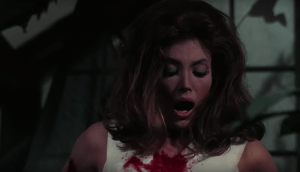

In this first scream, Danny and Wylie are outside on a walk when Danny sees someone in her bedroom window. She demands Wylie return home to see if her suspicions of an intruder are correct. Wylie parks Danny’s wheelchair at the top of a hill before leaving to investigate but Danny steers herself a bit down the hill to try and see what is happening. As she attempts to return to the top of the hill, her wheelchair begins to smoke and she begins to careen down the hill into oncoming traffic.

Disability is a theme front-loaded in this film with its connection to caregiving made explicit. Scenes depicting Danny in a lung-strengthening oxygen chamber that must be monitored, along with images of her struggling to move her wheelchair by herself frame Danny as having physical limitations that make her dependent upon her caregiver. Her scream is the moment in which Danny is finally able to give a literal voice to her fears. Removed from the home that has become her de facto prison, Danny can view her circumstances clearly for the first time. While she has long realized that her caregivers only perform their duties in the hope that they will inherit her fortune, she is only able to see the full extent of their duplicity when looking into the home from the outside. Her scream comes in tandem with her realization that she is in imminent danger and must notify authorities of Wylie and Kassia’s plot to kill her.

Danny’s attempts to confide her suspicions to her doctor are thwarted by his paternalistic and dismissive attitude. He quiets her pleas with a sleeping pill administered in her bedroom and the scene reminds viewers that the greatest threats to Danny are two institutions that are supposed to represent safety: the family home and the doctor/patient relationship. Far from serving as a sanctuary, the domestic space has become her prison and provides her caregivers with the privacy they need to carry out their crimes. The presence of the doctor, an outsider who is not part of the plot, should function to keep Danny safe, but his easy dismissal of her concerns illustrates the fallibility of human safeguards. It also reflects feminist concerns of the era that women were not empowered in their health care. A year after this film came out, Women and Their Bodies (later renamed Our Bodies, Ourselves) was published and contributed to a sea change in the doctor-patient relationship in its advice that women be active agents in their well-being (Norsigian). With Danny, we see the dangers that can befall women who yield to a paternalistic power that seeks to render difficult women quiet.

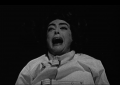

At the center of the plot against Danny is Kassia, a beautiful young woman whose machinations include gaslighting Danny to make her paranoid in her own home. But Kassia’s plot is brought to a screeching halt when Danny’s horde of cats corner Kassia and chase her up a ladder where she ultimately falls to her death.

Danny’s association with cats is meant to underscore both her age and her status as a single woman. When Kassia remarks on how unattached old women love cats, she is drawing upon a stereotype that reminds the audience that Danny lacks close human relationships. Not only does this frame Danny as someone who is isolated, but the sheer number of cats in Danny’s home suggests that Danny is prone to eccentric excess. The cats are a means by which to demarcate Danny as an Other in the minds of those around her and this status affects how her mental stability is perceived by institutional authorities, particularly her doctor.

Danny’s association with cats is meant to underscore both her age and her status as a single woman. When Kassia remarks on how unattached old women love cats, she is drawing upon a stereotype that reminds the audience that Danny lacks close human relationships. Not only does this frame Danny as someone who is isolated, but the sheer number of cats in Danny’s home suggests that Danny is prone to eccentric excess. The cats are a means by which to demarcate Danny as an Other in the minds of those around her and this status affects how her mental stability is perceived by institutional authorities, particularly her doctor.

Annoyed by her caregiving duties, Kassia moves from gaslighting Danny to psychologically torturing her — removing her beloved cats from the home. This proves to be a dire mistake as the cats return to the home seeking revenge. Their deliberate stalking of and intent to kill mimics Kassia’s behavior and is framed out in an intense sequence in which Kassia maintains eye contact with the cats. In a reflection of Linda Williams’ theory of the female gaze, the cats are positioned in the role of “monster” and as Kassia looks at them, she realizes an identification with them. Her scream, then, becomes a vocalized awareness of that identification. Symbolically, cats have long been associated with women, specifically single women (Frasin 160). While the stereotype of the single woman with cats often conveys a type of Otherness steeped in loneliness and gender non-conformity -which the first part of the film leans into-, here Danny’s cats upend that reading (Dupuis and Girme 315). As an extension of Danny, the cats represent a specific type of feminine power that has been nurtured. It represents a cyclical brand of caring in which Danny cared for the cats who, in turn, now care for her. It is a form of care that Kassia only recognizes as a source of power far too late.

Works Cited

Dupuis, Hannah E., and Yuthika U. Girme. ““Cat Ladies” and “Mama’s Boys”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of the Gendered Discrimination and Stereotypes of Single Women and Single Men.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 50, no. 2, 2024, pp. 314-328.

Eye of the Cat. Directed by David Lowell Rich, performances by Eleanor Parker, Gayle Hunnicutt, and Michael Sarrazin, Universal Pictures, 1969.

Frasin, Irina. “Of Cats and Women: A Cultural History of a Relationship.” Animal Life and Human Culture Anthrozoology Studies, 2022, pp. 158-182.

Norsigian, Judy. “Our Bodies Ourselves and the Women’s Health Movement in the United States: Some Reflections.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 109, no. 6, 2019, pp. 844-846.

Williams, Linda. “When the Woman Looks.” The Dread of Difference, edited by Barry Keith Grant, University of Texas Press, 2015, pp. 17-36.