Film Deets:

Director: Curtis Harrington

Screenplay: Henry Farrell

Actresses: Debbie Reynolds, Shelley Winters

Category: Hagsploitation

Themes: Grief Mental Illness

Why do these screams matter?

What’s the Matter with Helen follows two women, Adelle (Debbie Reynolds) and Helen (Shelley Winters), who flee their hometown for Hollywood when their sons are convicted of murdering a young woman. They open up a successful dance school for children but soon find their happiness threatened by a mysterious stalker.

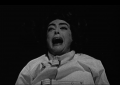

In our first scream, Helen is backstage at the dance school recital when she is consumed by visions of dead bodies. Her screams take on an added degree of hysteria when she then hallucinates that one of her colleagues has a knife.

Helen’s screams in this moment read as delusional paranoia since the audience is aware that the images Helen sees are not visible to any other characters. While Helen is legitimately afraid, the audience is not, and this juxtaposition frames Helen as an unreliable narrator. Unlike other hagsploitation films in which perceived delusions turn out to be real, underscoring that women’s voices and experiences should be believed, this film takes the opposite approach: it doubles down on Helen’s madness. Her instability not only marginalizes her within the narrative but also implies that she is a bad mother. Unlike Adelle, whose nurturing of the young dancers suggests her son’s failures are his own and not the result of poor mothering, Helen is framed as contributing to her son’s homicidal tendencies. Her screams, which disturb all around her including the children, convey a psychotic break that doesn’t humanize Helen as much as it pathologizes her.

Helen’s screams in this moment read as delusional paranoia since the audience is aware that the images Helen sees are not visible to any other characters. While Helen is legitimately afraid, the audience is not, and this juxtaposition frames Helen as an unreliable narrator. Unlike other hagsploitation films in which perceived delusions turn out to be real, underscoring that women’s voices and experiences should be believed, this film takes the opposite approach: it doubles down on Helen’s madness. Her instability not only marginalizes her within the narrative but also implies that she is a bad mother. Unlike Adelle, whose nurturing of the young dancers suggests her son’s failures are his own and not the result of poor mothering, Helen is framed as contributing to her son’s homicidal tendencies. Her screams, which disturb all around her including the children, convey a psychotic break that doesn’t humanize Helen as much as it pathologizes her.

Helen and Adelle are further differentiated in their approach to aging. In the beginning of the film, both women adopt a similar style of dress that reads as explicitly dowdy. But upon moving to Hollywood and adopting new names, their gender and age performance begins to radically differ. While Adelle dyes her hair platinum and embraces form-fitting, bright clothing as she juggles paramours, Helen remains her in brown, practical dresses which allow her to blend in with her surroundings. The film seems to be suggesting that while aging may not be optional, one’s performance of aging is entirely optional. Because the audience is expected to view Adelle’s interest in being appreciated for her physical appearance as normal, Helen’s disinterest in dressing to draw the male gaze is positioned as abnormal and further pushes her to the margins.

By connecting Helen’s mental unraveling to her implied bad parenting, the film adopts a conservative stance in keeping with the era’s framing of motherhood. Deviance of the sort illustrated by her son’s crimes was thought to be the result of bad parenting, with mothers taking the brunt of the criticism. In a time when the medical profession connected everything from schizophrenia to developmental delays to the actions of the parents, Helen is the film’s easiest scapegoat (Caplan and Hall-McCorquodale 346). But why is Helen demonized while Adelle is not? The answer resides in our next scream.

Having realized the extent of Helen’s issues, Adelle observes Helen tending to her beloved rabbits. Her silent, pensive gaze suggests that Adelle no longer knows how to handle Helen. A few moments later, Adelle hears Helen screaming and arrives to find a promotional cardboard cutout of herself covered in blood.

Functionally, this scream adds to the film’s dread-building by suggesting to the audience that the danger stalking the women is real and that it’s closing in on them. Because the scene comes on the heels of Helen seeing an image of a man standing outside in the shadows, the audience is left to wonder whether the man has finally infiltrated the shared home. But even this moment of trespass is used to imply an instability in Helen. Because the home is inhabited by two single women, something the film suggests makes the home simultaneously vulnerable and potentially abnormal, and because Helen is shown to be jealous of Adelle’s potential suitors, the presence of a man in the home reads as both potentially threatening and potentially stabilizing. The audience already knows that Helen is an unreliable narrator and so her fear response is not so much extended to the audience as it is questioned by the audience. This uncertainty about what exactly is transpiring at the home then escalates the narrative tension.

This scream also represents another way for the film to frame Helen as highly emotional and potentially erratic. Helen’s scream occurs in tandem with Adelle’s silence, with the film implying that Helen’s reaction is the extreme one. It is a bizarre narrative beat because objectively, Helen’s reaction is the expected normal response when confronted with a ghastly image. But instead, the film centers Adelle’s silence. While Helen unleashes a scream and then cowers in the face of the bloody spectacle, Adelle remains stoic and silent, approaching the cutout and removing the knife before shuffling Helen out of the room. The moment is a subtle bit of audience manipulation designed to Other Helen because no one who watches horror films imagines themselves as the character who panics and trembles in the face of danger. We imagine ourselves as the character who, like Adelle, confronts the danger.

The film extends Helen’s Otherness by connecting her bouts of hysteria with lesbian desire. Although the film’s intended LGBT subtext was dialed back in production, a fair number of gay markers made it into the final print. Helen continually vies for Adelle’s attention; she spends an inordinate amount of time commenting on Adelle’s beauty; and she verbalizes a vision of the future that prioritizes their relationship with one another. In an echo of the decade’s anti-women’s liberation rhetoric, which conflated feminism with lesbianism, Helen’s infatuation with Adelle is designed to be read as perverse. Compared to Adelle, whose heteronormativity is conveyed through her romantic relationship with Lincoln (Dennis Weaver) and her highly feminized appearance, Helen is a marginalized figure in both appearance and action. It is this status that her scream reiterates to both Adelle and the audience.

Works Cited

Caplan, Paula J., and Ian Hall-McCorquodale. “Mother-Blaming in Major Clinical Journals.” The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, vol. 55, no. 3, July 1985, pp. 345–353.

What’s the Matter with Helen. Directed by Curtis Harrington, performances by Debbie Reynolds, Shelley Winters, and Dennis Weaver, United Artists, 1971.