Film Deets:

Director: Adrian Lyne

Screenplay: James Dearden

Actresses: Glenn Close, Anne Archer

Category: Stalking

Themes: Adultery, Mental Illness

Why do these screams matter?

Adriane Lyne’s Fatal Attraction launched itself into the popular zeitgeist upon its release in 1987 with such a fervor that its title is still used as cultural shorthand to describe women driven to violence when they are unable to accept the termination of a romantic relationship. In the film, Alex (Glenn Close) embarks on an affair with a married man, Dan (Michael Douglas). When Dan breaks off the relationship, Alex’s actions become increasingly violent.

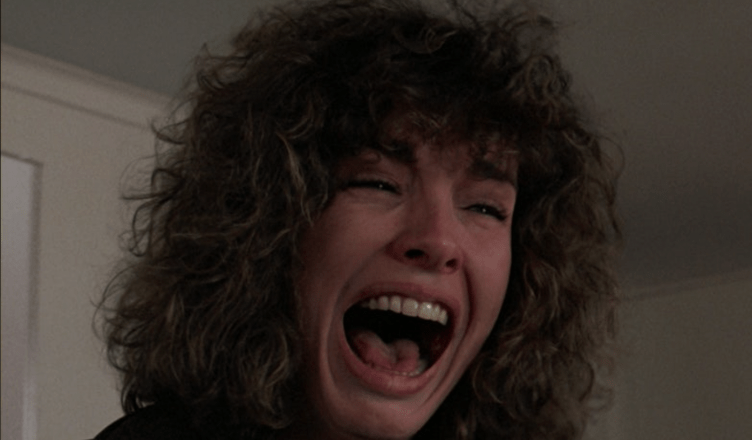

The film’s first scream erupts during a fight in which Alex demands respect from Dan as the future mother of his child, respect Dan refuses to give her.

When the film debuted, Alex’s interactions with Dan were cast largely as erratic and unreasonable. Film critic Roger Ebert describes Alex as “pathological” and “implacable,” while positioning Dan as a “happily married man” who falls victim to Alex’s machinations (27). Janet Maslin’s New York Times review also situates Alex as the “spurned lover” with “a streak of persistence and vindictiveness,” while characterizing Dan as a family man unable to resist Alex’s seductions (C10). Overtly patriarchal, these framings perpetuate the idea of a femme fatale whose sexuality is so great that it can upend a happy household. But it is Lawrence O’Toole’s review of the film as “a turgid tale of a crazy woman giving a nice guy and his family a hard time” that most clearly delineates how audiences were expected to respond to Dan and Alex (58-59). Because Dan is reduced to the role of an innocent bystander instead of a willing participant within the context of the affair, Alex is left to bear the brunt of responsibility for trespassing against the perceived sanctity of marriage. Judith Williamson (qtd. in Bromley and Hewitt) highlights this tension when she writes that Fatal Attraction is “a horror film in yuppy-melodrama land; its whole structure becomes blindingly clear once you realize that the part usually played by the Thing/the Blob/the Bug is played by the SWW (single working woman)” (28).

But here, Alex’s scream upends the simple aggressor/victim dichotomy by forcing the audience to engage with her pain. Her famous statement, “I will not be ignored, Dan” has been parodied endlessly as a cautionary tale of threatening instability. Yet, when considered within the context of the entire scene, it reads more as a reclamation of space in that Alex is unwilling to let Dan erase her and her unborn child’s needs. Pushing back on Dan’s insistence that she’s “sick,” by calmly pointing out that she’s just refusing to let him treat her “like some slut you can bang a couple of times,” Alex demonstrates a refusal to allow Dan to (re)frame the events of their relationship to serve his victim status. While Alex’s subsequent actions in the film are horrific, her reactions at this moment aren’t quantifiably excessive. Not only is Dan gaslighting Alex, but he’s also gaslighting the audience into seeing Alex as the monster in the relationship. Her anger only culminates in a scream after Dan has verbally and physically assaulted her. While this scream is clearly coming from a place of frustration and anger, it is also a means for Alex to reclaim her autonomy, an autonomy that Dan’s tirade was meant to undermine. The force of her scream places Alex in tension with Dan’s verbal dismissal of her needs such that it forces the audience to read the dynamic between the two as oppositional. This, in turn, creates space for the audience to sympathize with Dan. That Dan’s gaslighting is ultimately successful in how this scene has traditionally been read says more about how society views sexually aggressive women than it does about Alex.

Our second scream further solidifies Alex’s status as the monster of the film. Upon returning home, Dan’s wife, Beth (Anne Archer), approaches a boiling pot left on the stove. When she removes the cover, she is distraught to find the body of the family pet.

As the scene unfolds, the camera cuts between Ellen (Ellen Hamilton Latzen), Beth and Dan’s daughter, approaching her bunny hutch and Beth entering the family home. The rapid cutaways between the two scenes suggest that the danger represented by Alex has moved away from Dan and is now poised to invade the family home. The reveal that Alex has murdered the family pet and has been inside the home signals to the audience Alex’s complete disregard for boundaries. Because monsters represent “moral or spiritual depravity,” Alex’s behavior of breaching the domestic sphere and exposing an innocent child to violence erases any sympathy for the character and positions her unilaterally as the film’s Big Bad (Asma 142).

Beth’s screams of horror pick up where Ellen’s distraught cry for her daddy ends and the entwining of these two vocal responses is intentional. Not only does this continuum position Beth and Ellen as blameless victims, but it also feeds into the film’s Madonna/Whore narrative. Beth and Ellen’s “innocence” is meant to stand in opposition to Alex’s aggressive sexuality in a dichotomy that is overtly patriarchal. Instead of holding Dan accountable for his decision to willingly engage in a relationship with Alex, the film casts him as a “good” family man who fell victim to the temptations of a sexually aggressive woman. When Ellen yells for her father, she is reminding the audience that despite his lapse in judgment, Dan should be seen as a hero protecting his family and not as a monster. And when Beth extends her daughter’s cry with her own screams and the camera cuts to Dan’s frantic response to his wife’s cries, we are reminded that this is a family unit in danger. The protection of that family then becomes the means by which the film writes off Dan’s culpability in the affair and his subsequent abusive actions.

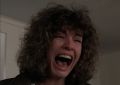

The struggle between family security and outsider menace reaches its climax in the final screams of the film. As Beth prepares for a bath, a disheveled Alex appears and the two begin to struggle before Dan intervenes.

With its jump scare, brutality, and fake-out death scene, it is this sequence in the film that arguably pushes the film out of thriller territory and into horror. Interestingly, it is also where Alex’s mental illness is most clearly delineated for the audience. As she threatens Beth, she repetitively rubs a knife against her thigh. As the blood blooms on her white dress, Alex shows no awareness of the pain suggesting that she is in the midst of a psychotic break. The cadence of her speech also indicates that she has disconnected, at least to a degree, from the events unfolding in front of her. The film capitalizes on this revelation not to paint a complicated portrait of a woman whose mental instability is exacerbated by Dan’s horrendous treatment, but to simplify her actions into those of a woman consumed by monstrous jealousy.

Because the confrontation begins by having Alex and Beth pitted against one another, the screams of each woman operate to create a boundary between them that positions Alex as the threat and Beth as the innocent. Consequently, when Dan enters the fray on the side of Beth, his screams work in tandem with Beth’s such that her status as an innocent becomes his by extension. Their united front, evident by their combined vocal responses, signals to the audience that the domestic idea is only fractured but not broken in a reflection of the conservative rhetoric of the decade. As the interloper, Alex must be dispatched and silenced which is exactly what happens.

Works Cited

Asma, Stephen T. On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Fatal Attraction. Directed by Adrian Lyne, performances by Michael Douglas, Glenn Close and Anne Archer, Paramount Pictures, 1987.

Hewitt, Pamela, and Susan Bromley. “Fatal Attraction: The Sinister Side of Women’s Conflict about Career and Family.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 26, no. 3, 1992, pp. 17-23.

Ebert, Roger. “Fatal Attraction.” RogerEbert, 18 Sept. 1987. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

Maslin, Janet. “Film: ‘Fatal Attraction’ With Douglas and Close.” The New York Times, 18 Sept. 1987. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

O’Toole, Lawrence. “Brief Encounters.” Macleans, 21 Sept. 1987, pp. 58-59.

Williamson, Judith. “Nightmare on Madison Avenue.” New Statesman, 15 Jan. 1988, pp. 28-29.