Film Deets:

Director: Mariama Diallo

Screenplay: Mariama Diallo

Actresses: Regina Hall, Zoe Renee, Amber Gray

Category: Systemic White Supremacy

Themes: Racism, Academia

Why do these screams matter?

Directed by Mariama Diallo, Master (2022) is a pointed critique of how white supremacy operates (and at times flourishes) within the structures of academe. The film follows the trajectories of two women at an elite university- Gail Bishop (Regina King), a senior professor navigating her first year as the institution’s first Black master and Jasmine Moore (Zoe Renee), a first-year student increasingly interested in the tragic story of a former student.

Our first scream occurs when Gail enters the attic of her new home and discovers the painting the school commissioned to mark her appointment. Peeling back the cover, she is horrified to see maggots spilling out of the eyes and mouth of the portrait.

Gail’s scream in this moment is a multilayered hybrid of shock, revulsion, and confusion and it provides the audience its first understanding of how context morphs university markers from affirming to threatening. In a prior scene, the artist explains how Gail’s portrait is a disruption to the white, male faces of previous university masters, and it is clear from her reaction to this observation that she is proud of her accomplishments. Yet, the discovery of the painting in the same attic that houses racist scholarship and that formerly served as the maid’s quarters signals that the creation of the portrait was simply a performative way for the university to convey its commitment to diversity. Once accomplished, the portrait is forgotten and left to collect dust. The scream Gail emits as she sees the portrait’s maggot infestation is clearly a result of the surprise at the grotesque spectacle before her. But it is also fueled by a dawning realization that there is something (quite literally) rotten about the school’s treatment of her portrait: it conveys not only disrespect for the artifact but, more importantly, for Gail.

Gail’s scream in this moment is a multilayered hybrid of shock, revulsion, and confusion and it provides the audience its first understanding of how context morphs university markers from affirming to threatening. In a prior scene, the artist explains how Gail’s portrait is a disruption to the white, male faces of previous university masters, and it is clear from her reaction to this observation that she is proud of her accomplishments. Yet, the discovery of the painting in the same attic that houses racist scholarship and that formerly served as the maid’s quarters signals that the creation of the portrait was simply a performative way for the university to convey its commitment to diversity. Once accomplished, the portrait is forgotten and left to collect dust. The scream Gail emits as she sees the portrait’s maggot infestation is clearly a result of the surprise at the grotesque spectacle before her. But it is also fueled by a dawning realization that there is something (quite literally) rotten about the school’s treatment of her portrait: it conveys not only disrespect for the artifact but, more importantly, for Gail.

The act of consigning the portrait to the attic isn’t a decision that can be dismissed as an oversight. Rather, it is a microaggression that speaks to Gail’s precarity within academia. Despite being a senior scholar, Gail is not accorded the same respect as the senior white males who came before her. A microinsult, the act becomes what Aparajita Sagar calls an “apparent inconsequentiality,” meaning that it can be replicated without arousing suspicion (11). Gail’s scream in the attic makes visible and consequential these microaggressions and is the audience’s first understanding that the threat of violence facing Gail is both overt and subtle. It is an insidious cruelty that separates Gail from her white peers who lack a similar understanding of the historical magnitude of racially charged microaggressions.

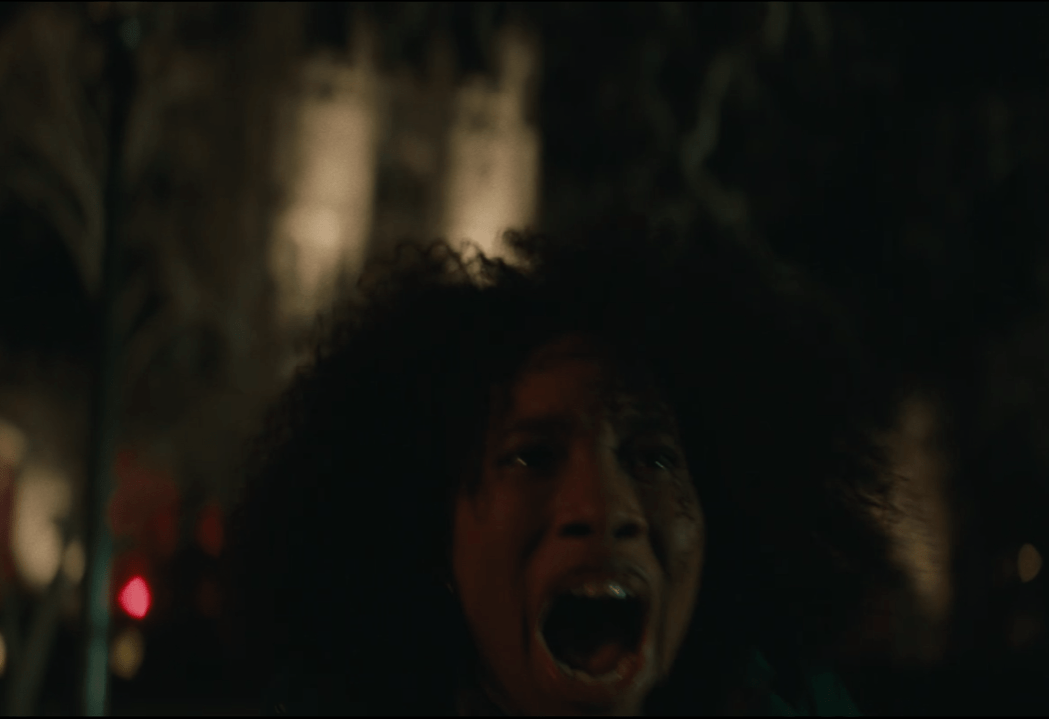

The subtlety of microaggression gives way to overt racism in our next scream. Jasmine, who is the only one from the house not to have left the campus for Thanksgiving, begins to suspect she is not alone. As an alarm starts blaring, Jasmine is stunned to find a burning cross outside the house. Immobilized, she is unable to move until Gail arrives and intervenes.

Steeped in historical meaning, the significance of a burning cross and the hateful racism it conveys cannot be overstated. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the image of a burning cross has been used to incite terror since the early 1900s (“Burning Cross”). But this is not a crime consigned to the past. The Southern Poverty Law Center notes that in 2012, for instance, a burning cross was used as a means of intimidation against an interracial couple in Florida (Morlin). In Master, the burning cross is an abhorrent culmination of violence against Jasmine that starts with microaggressions by her white and wealthy peers and ends with a fiery and unconcealed symbol of hate. Frozen at the sight, Jasmine’s safety is ensured by Gail who arrives on the scene and whose screams startle Jasmine to action.

Gail’s screams result from concern for Jasmine’s well-being and reflect how members of marginalized communities often care for one another in times of turmoil. As the older woman, Gail has the experience to recognize that the threat to Jasmine in this moment is not only physical but also emotional. Her screams here acknowledge the historical legacy of racism and anti-Blackness while also ensuring that the audience understands modern reverberations of that legacy within higher education. In the film, the school’s response to the violence is to create a marketing campaign using the faces of the university’s few faculty and students of color to misrepresent the university’s diversity. This approach, which is shocking in its realism, speaks to how often campuses handle issues of racism performatively instead of substantively.

The university’s failure to address campus racism in a meaningful way has dire consequences which are represented in our next scream set. Believing that she is being stalked by the spirit of a slain witch, Jasmine falls from her dorm room window as she flees her attacker.

The face of Jasmine’s attacker is never revealed which leaves the audience to conclude one of two things. Either she is being haunted by the apparition of Salem-era witch Margaret Millett or she is being targeted by Dr. Liv Beckman (Amber Hunt), a professor Jasmine reported for grading bias. Either scenario is rooted in racism and reframes Jasmine’s screams during the attack. If we accept that she is being hunted by a ghost, Jasmine’s screams as she attempts to run to safety imply that she is literally being stalked by a past rooted in racism. We know that Millet was part of an order that associated (and still associates in the present) Blackness with the Devil. Jasmine’s cries for help come on the heels of her discovering the diary of Louisa Weeks, the school’s first Black undergraduate, who was similarly stalked before her death. In this moment, the archaic past intrudes upon the present leaving Jasmine desperate, a state she is only able to convey through her screams.

But the film offers a second possibility to viewers. We learn that Liv Beckman is possibly a white woman who has been passing as Black and that she dons a coat similar to the one worn by the figure stalking Jasmine. In this scenario, Jasmine’s screams become an even more complicated hybrid of terror and historical trauma. Evoking the real life cases of Jessica Krug and Rachel Dolezal, two white professors who posed as Black women, the question of Liv’s racial identity is never known to Jasmine but it is to the viewers (Jackson; Johnson et al.). We are positioned to call into question Liv’s racial performance and to question how that might contribute to her monstrosity. As Marquis Bey and Theodora Sakellarides note in their consideration of Dolezal’s identity cooption, complicated racial history “is sidestepped, bypassed, and cheapened when a person of racial privilege such as Dolezal attempts to disavow their privilege and thus their complicity in that violent history” (34). If Liv is a white woman claiming an identity and a history that is not hers to own, her actions are quantifiably monstrous because she’s trading on a history of trauma and brutality for gain. And that possibility increases the horror contained in Jasmine’s screams because it implies that not even those who look like allies can always be trusted.

Our final scream occurs when Gail notices a light in Jasmine’s window. Suspecting something is wrong, Gail is devastated to discover that like Louisa Weeks before her, Jasmine has died by suicide.

The discovery of Jasmine’s body is preceded by Gail’s return to the campus where she is greeted by the study body screaming to signal the end of the school year. What is depicted in the beginning of the film as an innocuous tradition of community building becomes sinister when reframed through Gail’s and Jasmine’s experiences. The screams emitted by the student body echo a mob, the chorus of which provides the backdrop to Gail’s discovery of Jasmine. Because Gail had previously convinced Jasmine not to leave the school, despite the very evident toll it was taking on Jasmine’s health, her screams in this scene are shrouded in guilt that she has perpetuated an academic culture harmful to Black women like Jasmine. Rather than helping Jasmine find an academic environment in which to flourish, Gail encouraged her to continue to navigate the school’s toxic university structures that privilege whiteness.

But the film never lets us forget that Gail is also a victim of the same academic environment that values the labor of white men and women over the labor of women of color because, as Amelia N. Gibson notes, “Being the only, or one of two, faculty of color (FOC) in a department brings with it a sense of structural precarity, as the faculty member’s success is often reliant on her ability to educate key allies about these issues without arousing fragility or defensiveness” (218). Gail is enmeshed in a system the full toxicity of which she only comprehends in the wake of Jasmine’s death. Because Jasmine died by hanging, the image that confronts Gail mirrors a lynching. Gail’s screams are certainly for Jasmine and the profound loss her death represents but they are also an acknowledgement of a brutal history, the impacts of which are still intensely felt.

Works Cited

“Burning Cross.” Anti-Defamation League, 3 May 2022. Accessed 18 Aug. 2022.

Gibson, Amelia N. “Civility and structural precarity for faculty of color in LIS.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, vol. 60, no. 3, 2019, pp. 215-222.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. “The Layered Deceptions of Jessica Krug, the Black Studies Professor Who Hid That She is White.” The New Yorker, Sept. 12, 2020.

Johson, Kirk, et al. “Rachel Dolezal, in Center of Storm, Is Defiant: ‘I Identify as Black’.” The New York Times, June 16, 2015.

Master. Directed by Mariama Diallo, performances by Reginia Hall, Zoe Renee and Amber Gray, Amazon Studios, 2022.

Morlin, Bill. “Cross-burnings Still a ‘Tool of Fear’ Used by Racists.” Southern Poverty Law Center, 10 April 2017. Accessed 18 Aug. 2022.

Sagar, Aparajita. “Institutional Climates and Women Faculty of Color: Overcoming Aversive Racism and Microaggressions in the Academy.” Navigating Careers in the Academy: Gender, Race, and Class, edited by Mangala Subramaniam, Purdue University, 2019, pp. 4-15.