A paradox haunts the humanities today. Humanities scholars are producing vital insights about the most pressing challenges in 21st-century societies, about the histories that have shaped us and the cultural resources that might enable us to cultivate more just communities and fuller lives. But much of this knowledge circulates only among experts in universities and is inaccessible to most people.

In recent years, a growing number of humanists have committed themselves to resolving this contradiction. Although scholars who identify with the project of the “public humanities” have varied goals and work in varied ways, two primary impulses characterize this movement. First, public humanists are inventing strategies to share the most sophisticated humanities research with the broadest possible audiences. Second, many are collaborating with artists, activists, and people from all walks of life in order to produce and circulate knowledge that reflects the diversity of our society, including perspectives and domains of experience that have often been marginalized or excluded from research universities.

I am committed to the public humanities because I believe that humanistic knowledge is too precious to be confined to the university alone. I believe that by collaborating more broadly and creatively, we can revitalize the civic mission of the humanities.

My own research has focused on the role of literature in the development of movements for economic justice and for racial and gender equality in the United States. My understanding of these movements and the power of literature has been transformed by practical collaborations with artists, activists, civic leaders and residents from across the city in which I live.

These collaborations have enabled me to share my expertise about literature and politics with more varied and diverse communities. They have exposed me to bodies of knowledge and ways of knowing that lie outside the familiar archives and procedures of humanities research. They have enabled me to develop more flexible and expressive strategies for creating and sharing knowledge. In my experience, working with others to create a play, build an oral history archive, conduct a public forum about a crisis in our community, or discuss a work of literature in a union hall or church basement, makes humanistic knowledge come alive. These activities have reminded me that people across our society are hungry for the humanities. They remind me that ideas matter, that art gives us pleasure, and that scholars can be collaborators in the daily work of social change.

I do not view these public humanities practices as substitutes for more conventional modes of scholarship. They are extensions and elaborations, ways of sharing, diversifying and enriching the knowledge that emerges from academic research.

These public humanities practices now influence most aspects of my work, including the projects described below.

Much of my own work in the public humanities has been made possible by the South Side Initiative, a wide-ranging initiative of democratic university-community collaboration in the city of Bethlehem, which you can learn about here.

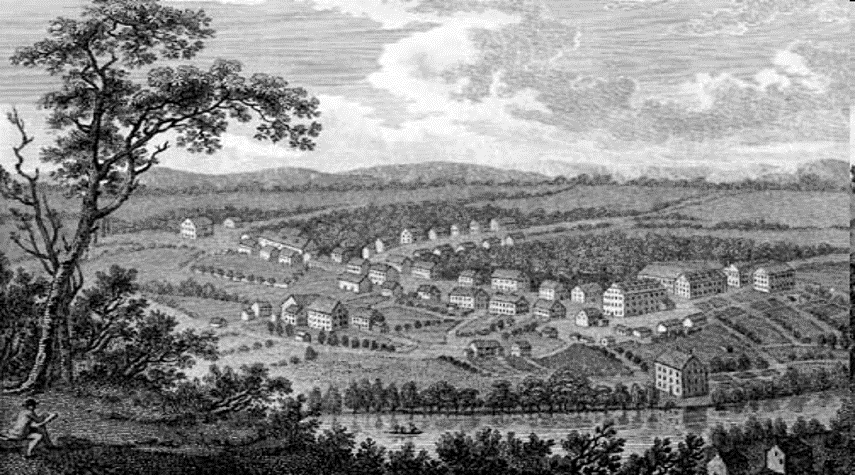

Bethlehem: American Utopia, American Tragedy

I am currently writing an experimental book about the city of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where I live and teach. It is a work of public humanities scholarship both in the sources it rests upon and the audiences it seeks to reach. The book explores the aspirations for equality cultivated and implemented by the people of Bethlehem over the course of three centuries, as well as the structures of power that have constrained them. In writing the book, I have drawn on decades of academic research but also on an archive of working-class oral history and community memory constructed through partnerships with a range of community organizations. I am writing the book both for scholars in American Studies and a broad general readership. The mode of composition draws on what I have learned as a scholar of literary modernism. Like some of the writers I have explored in my literary criticism – including Langston Hughes, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), and John Dos Passos – I seek to create a narrative that can enable readers to feel the richness of past egalitarian ideas and experiments and extend them flexibly into the future. In this way, the book, seeks to contribute to contemporary discussions of what equality has meant, and might yet mean, in the United States.

I have also pursued a range of other public humanities collaborations in tandem with my research for the book. I describe a few of these below

Hidden Seed

Hidden Seed is a play about the African, Native American and European women who helped found the city of Bethlehem in the middle of the 18th century. Drawing on years of historical research for my book, I wrote this play in collaboration with Bill George, co-founder of Touchstone Theatre, for performance as part of Touchstone’s 2019 Festival UnBound. The play introduced local audiences to little-known aspects of the city’s history, including the founders’ remarkable egalitarian achievements and their betrayal of their own ideals by enslaving Africans and building on land stolen from native people. Through post-performance community dialogue, residents discussed the kinds of equality we aspire to today and the histories of violence that constrain us. Television broadcast expanded the circle of conversation further. Although I had published scholarly articles about Bethlehem’s founding, this collaboration with theater artists transformed my understanding of the city’s history and its 21st-century implications. For more details, click here.

Finding H.D.

I had begun studying and writing about H.D., one of the most influential poets of the 20th century, before I moved to Bethlehem in 1999. I explored her significance for the modernist literary tradition in my book, Mourning Modernity. Because Hilda Doolittle’s family helped to found the city of Bethlehem and many of its modern institutions, I am writing about the poet and her family in my book-in-progress and I summarized this research in a recent scholarly article. But my understanding of H.D., the most influential literary figure born in Bethlehem, has been dramatically enriched by collaborating with local artists, LGBT activists, public librarians, and city residents in a multi-year community exploration of her life and work. Through public readings, lectures and colloquia, reading groups, walking tours, a commissioned portrait for the public library, a concert, and the creation of an original mixed-media play, The Secret, we invited the people of Bethlehem to explore H.D.’s legacy and to embrace this queer, feminist visionary as a presiding literary spirit of our city. By searching for H.D., we set out to learn who we have been as a community, and who we might become. By finding her together, and naming our discoveries, we seek to shift and enrich the story of our city. For more details, click here.

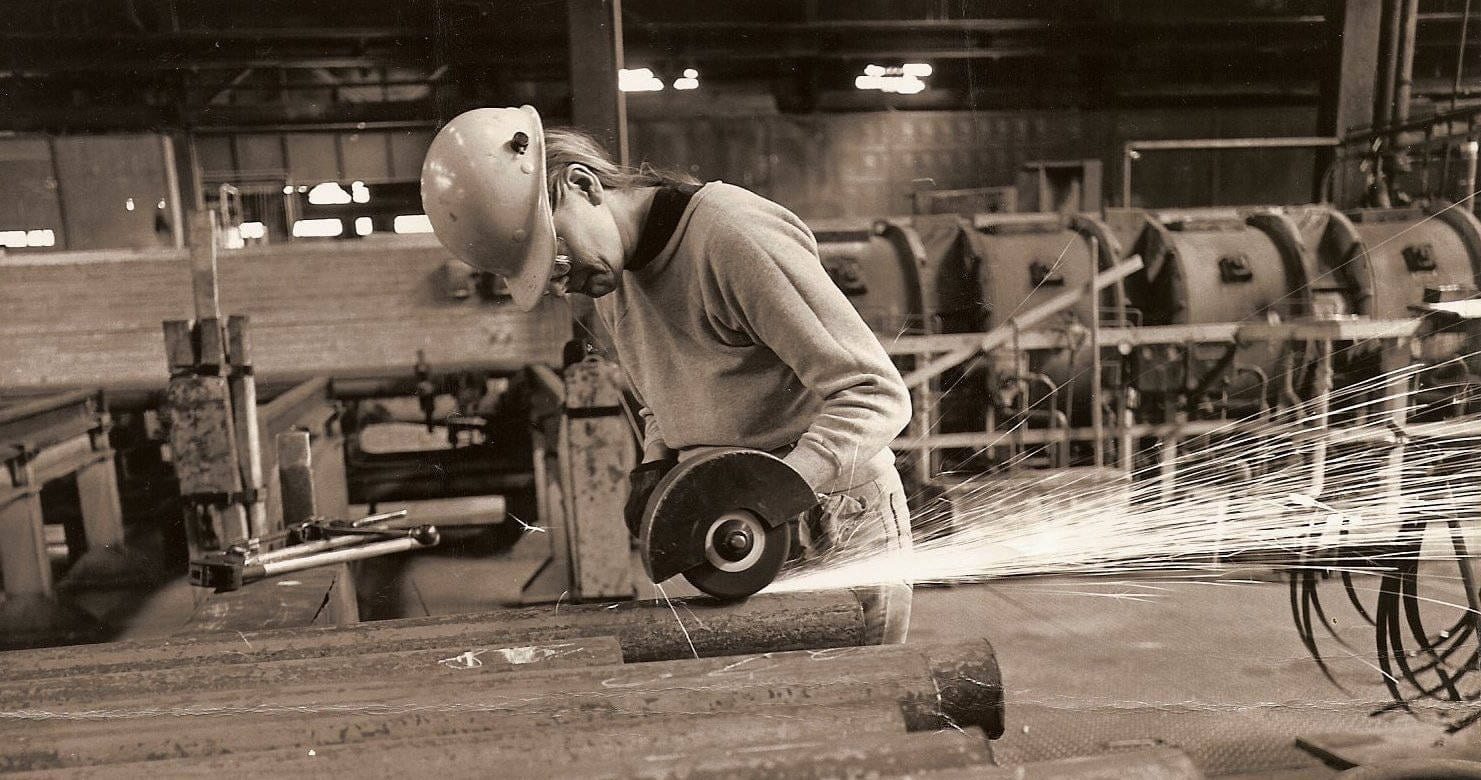

Women of Bethlehem Steel

In order to write a book about Bethlehem’s history, I have spent years researching the Bethlehem Steel corporation, the history of the steelworkers union, and the experience of the immigrant steelworker families who built South Bethlehem. Scholars and community members alike usually tell the story of Bethlehem’s iconic steel industry as a story about male industrial workers, male engineers and male executives. Women’s role is often ignored or erased, including the experience of women who integrated the plant in the 1970s, after a Supreme Court consent decree forced the company to abandon a century of discriminatory racial and gender hiring practices. I leapt at the chance to collaborate with dozens of women who worked at the Steel, with members of the Steelworkers Archives, and with Lehigh colleagues and students to create the Women of Bethlehem Steel, a fully searchable online database of video interviews, photos and documents exploring the role of women in the city’s steel industry. At a series of public forums these women explained what it meant to earn a union wage and to do the dangerous work that men in their families had done for generations. They shared their stories of harassment and discrimination, empowerment and solidarity. At these widely reported public events, audiences discussed the meaning of these experiences for women today and how we might create the conditions that would enable all girls and women to thrive in our post-industrial city. For more details click here.