In a session hosted by the Research Office, two Lehigh faculty shared best practices for submitting a proposal to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Specifically, the discussion centered on the philosophy of this federal agency and advice for what to do before you even begin writing a full proposal in response to a funding opportunity announcement.

Anand Jagota (Chair, Bioengineering) and Israel Wachs (Professor, Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering), who led the presentation, have decades of continuous funding from the DOE and are incredibly knowledgeable in what the agency is looking for during the application review process.

So you’d like to apply for DOE funding? In addition to reviewing the instructions in the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) here are five things you should do before you begin writing a full proposal:

- Review the DOE website and locate the Research Areas and Reports and Activities of the Program that best fits with your field of research.

- It is very important to pay attention to the DOE Research Needs. For example, the Basic Energy Sciences (BES) Program seems to prefer fundamental, long-term energy-themed research topics that allow you to go deeper and deeper into a particular subject matter.

- Thoroughly review the information provided in the FOA. Similar to other agencies, the program managers spend a lot of time reviewing and editing the funding opportunity announcement before it’s released. They use it as their guide for deciding whether proposals meet the criteria, and it would benefit faculty to use it as their guide for writing the proposal.

- Work with your CGS to register in Grants.gov, become familiar with the new Workspace platform, and design a workflow process that works best for your team.

- Make contact with the current DOE Program Manager. Initial contact may take several forms, for example an email requesting a phone call that leads to an in person meeting while attending a research-related conference.

- Relationship building and collaboration among top institutions and laboratories seems to be an important consideration during the review process.

- Review your preliminary data and prepare a White Paper (2 pages) to send to the Program Manager.

- This agency prefers to see relevant and significant preliminary data; think in terms of “60% is what you did, 40% is what you will do if funded.”

- Be prepared to receive limited feedback for a declined proposal.

- DOE is a little less transparent (than some of the other agencies) in terms of sharing reviewer feedback. This agency is also a little less clear with explaining why your proposal was declined, and it is therefore difficult to determine which areas need improvement in order to prepare a strong resubmission.

- From experience, there are two criteria for getting funded 1) The proposal needs really good reviews from each committee member, and 2) The Program Manager has to be convinced that your project fits, and has long-term potential (which could mirror a subjective review).

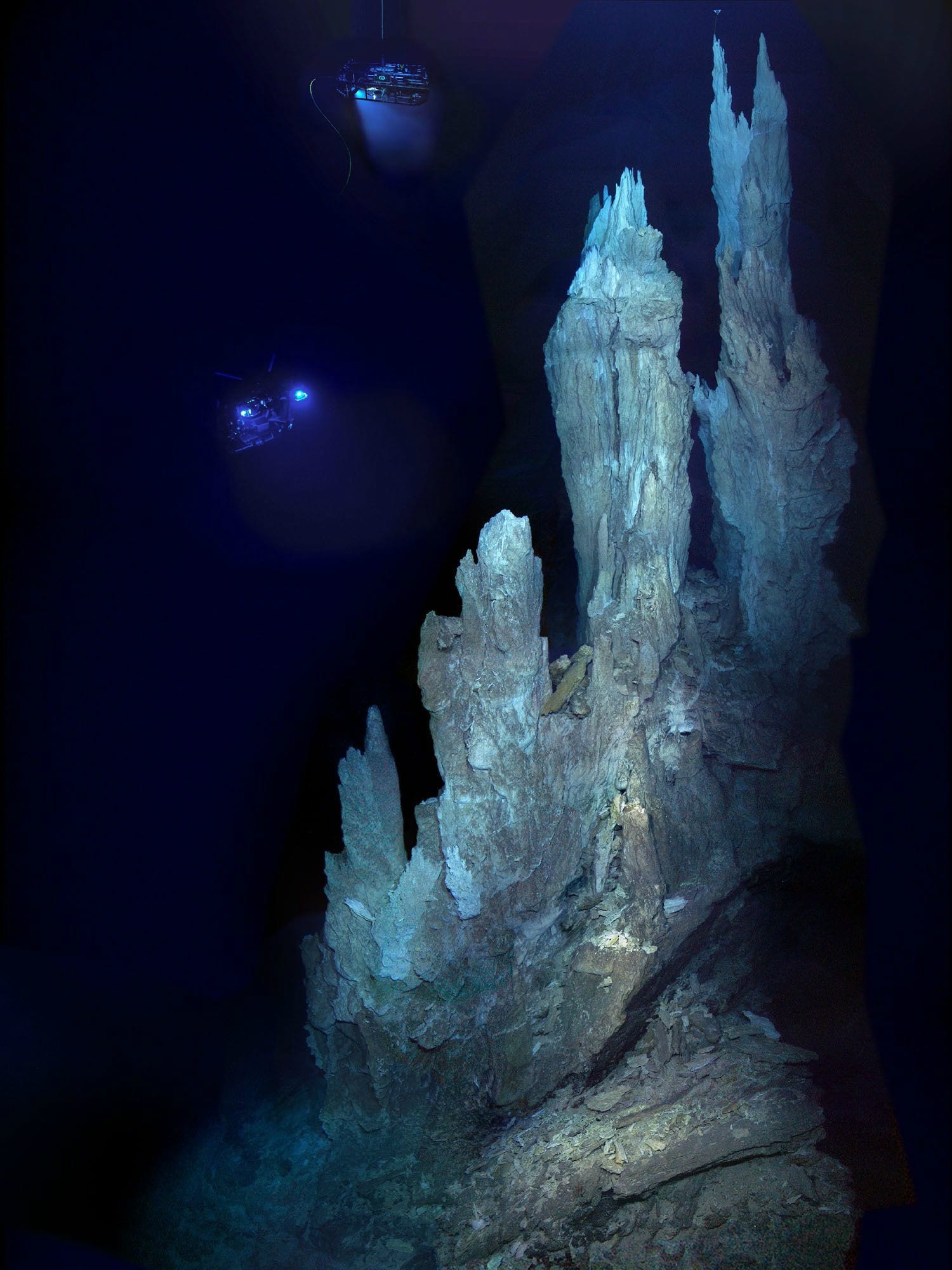

temperatures and pressures. Similar conditions exist at two other known hydrothermal fields in the Atlantic Ocean, Lost City and Rainbow, where vent fluids expelled at the seafloor are rich in dissolved hydrogen gas. The enrichment in hydrogen gas means there is great potential for the chemical, or ‘abiotic’ formation of organic molecules like methane and formic acid – possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth

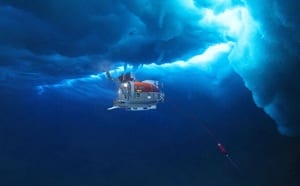

temperatures and pressures. Similar conditions exist at two other known hydrothermal fields in the Atlantic Ocean, Lost City and Rainbow, where vent fluids expelled at the seafloor are rich in dissolved hydrogen gas. The enrichment in hydrogen gas means there is great potential for the chemical, or ‘abiotic’ formation of organic molecules like methane and formic acid – possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth  high-resolution seafloor maps and track down the vents by measuring chemical clues, such as particle-rich water and locations where the seawater is relatively rich in hydrogen and methane. Once the exact location of the vent site is known, the Nereid UI will transform and launch again, now tethered by a fiberoptic cable the width of a human hair. I will equip it with titantium syringes that can collect vent fluid samples and maintain seafloor pressures until the samples are back onboard the ship. There my colleagues and I will begin the exciting task of understanding the origin of these fluids, how they sustain life on the Arctic seafloor, and what this means for life detection on other planetary bodies in our solar system and beyond.

high-resolution seafloor maps and track down the vents by measuring chemical clues, such as particle-rich water and locations where the seawater is relatively rich in hydrogen and methane. Once the exact location of the vent site is known, the Nereid UI will transform and launch again, now tethered by a fiberoptic cable the width of a human hair. I will equip it with titantium syringes that can collect vent fluid samples and maintain seafloor pressures until the samples are back onboard the ship. There my colleagues and I will begin the exciting task of understanding the origin of these fluids, how they sustain life on the Arctic seafloor, and what this means for life detection on other planetary bodies in our solar system and beyond.