Jenna Lay is Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the English Department of Lehigh University.

The academic lifecycle is an unusual one. Years unfold in months-long stretches of time: fall and spring semesters devoted to teaching and running academic programs; summer, as Nicholas Sawicki suggests in his post, offering time for larger projects, writing, and travel—like the archival work Elizabeth Dolan describes. The rhythm of an academic career offers similar ebbs and flows, as the boisterous conversation of graduate coursework transforms into the solitary discipline of a dissertation, which, in turn, enables the intellectual growth that will foster new forms of engagement in the classroom and in a broad range of communities.

As a pre-tenure faculty member at Lehigh, I spent the last six years building on that foundation: transforming the knowledge and skills gained through graduate study into the research, teaching, and service that structure academic days, months, and years. I can now hold the most material of these transformations in my hands: my first book, Beyond the Cloister: Catholic Englishwomen and Early Modern Literary Culture, was published this month by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

With my book’s publication, I’ve been thinking about the research lifecycle, and especially about how scholars transition from one project to the next. Watching my words evolve from malleable files on my computer to the relative fixity of a printed book, I’ve become increasingly convinced that a research project is never truly complete: that the questions answered will inevitably spark new ideas and areas for exploration. And yet this is still a summer of endings and beginnings, of one project completed and another just developing. In this blog post, I’ll say a bit about what a transitional period like this entails: what did my summers look like when I was working on Beyond the Cloister? How does this summer differ?

The summers after my first, second, and third years at Lehigh were largely devoted to travel: in libraries and archives located in London, Oxford, Paris, and Lille, I read manuscripts written by and about the seventeenth-century English nuns at the center of my first book project. This travel also enabled me to attend conferences in my field, led to articles and essays on related topics, and facilitated the process of writing the book itself. The summers after my fourth and fifth years were wholly focused on writing and revising: first, completion of the book manuscript in my fourth summer, and then revision of that manuscript based on the excellent feedback of two anonymous readers for my press in my fifth summer.

During this past academic year, I finished my final work on the book (copyedits, checking the proofs, creating an index)—which meant that this summer would be my first Lehigh summer not dedicated to that aspect of my research. What does a summer look like, when not consumed by a project that consumed a decade of summers?

First, it involves sharing the research behind the book with new audiences. With the support of a Faculty Grant for International Connections, I traveled to Ireland in May to explore the possibility of a Ph.D. exchange between Lehigh and NUI Galway. While there, I met with colleagues studying early modern nuns and the broader reception and circulation of early modern women’s writing through the RECIRC project, directed by Marie-Louise Coolahan. I was delighted to have the opportunity to give a talk on Beyond the Cloister to this wonderful group of scholars. Since then, I’ve been working on a review essay that summarizes recent work on early modern nuns—a great opportunity to highlight some of the exceptional scholarship that has been published since my book went to press, and to offer my thoughts on avenues for future research in the field.

At the same time, I’ve pursued opportunities to begin work on my next book, a study of how women participated in the reception and interpretation of the Bible in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England—and especially how their Biblical exegesis helped shape the forms of early modern literature. Like my first project, this research will require substantial archival research, as I explore the manuscripts written by and for early modern women.

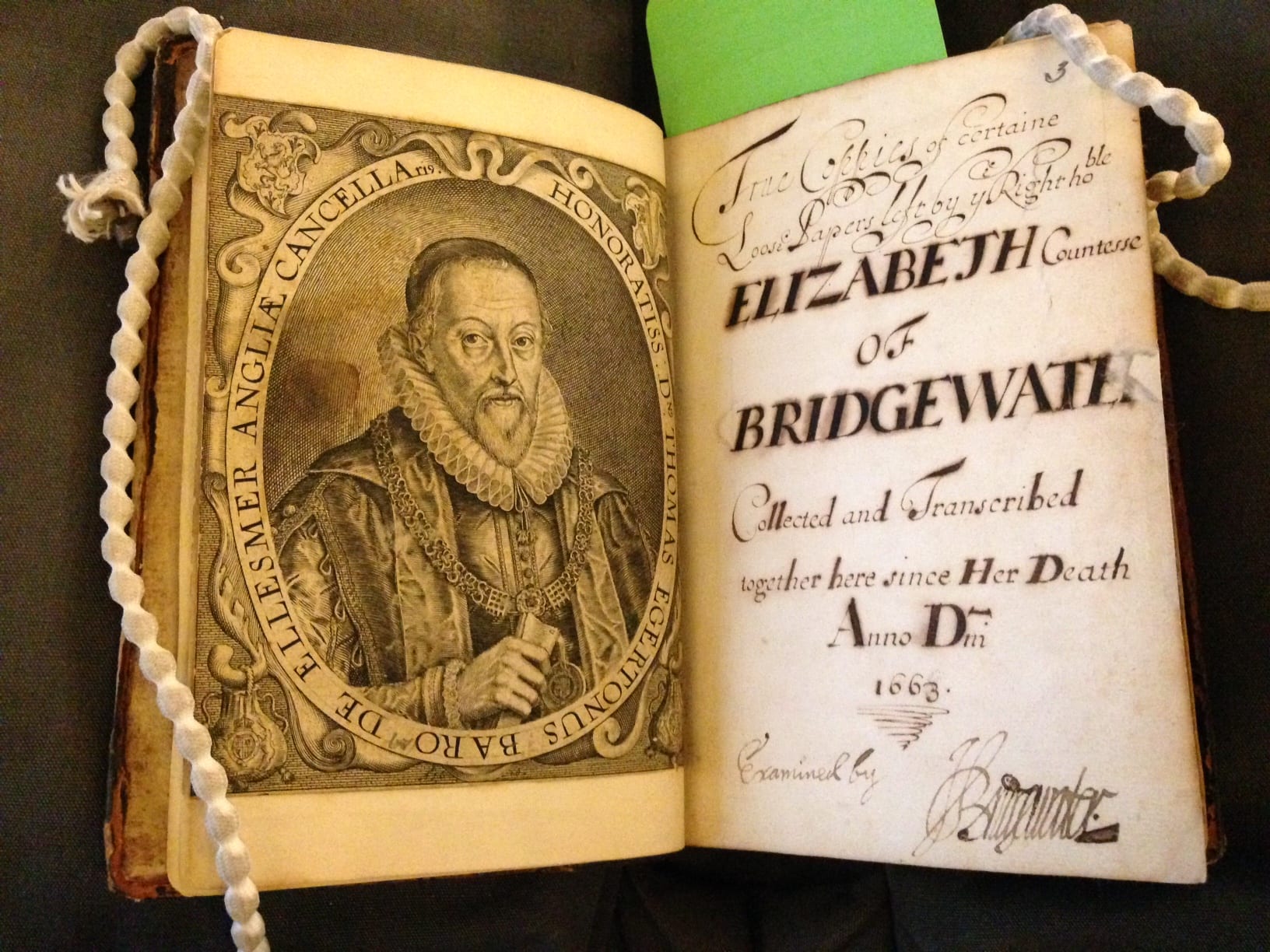

To begin this process, I visited the British Library for a preliminary examination of relevant materials. Among many highlights of the trip, I was especially intrigued by the

prayers and meditations of Elizabeth Egerton, the Countess of Bridgewater, (pictured at left) which were collected into scribal copies by her husband after her death. Egerton’s prayers for her children, especially those who died in their infancy, offer a heartbreaking glimpse into the emotional life of an early modern woman. At the same time, these meditations show Egerton reading her Bible: they include Biblical citations in the margins, and treat the Pauline epistles as a site of negotiation and critique. In future summers, I’ll be returning to the British Library and other archives in England to further explore the manuscript record.

I was also delighted to be admitted to a week-long course offered by the Rare Book School on “The Bible and Histories of Reading.” This course, taught by Peter Stallybrass, Annenberg Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English at UPenn, and Lynne  Farrington, Curator of Printed Books in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, offered a fantastic opportunity to immerse myself in the material history of the Bible, from scroll to codex, and to gain greater familiarity with the resources available at Penn. As I develop my next book, this course will serve as an essential background to my work on women’s readings of the Biblical text and the many uses they made of the Bible as a material book—a project for the summers to come.

Farrington, Curator of Printed Books in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, offered a fantastic opportunity to immerse myself in the material history of the Bible, from scroll to codex, and to gain greater familiarity with the resources available at Penn. As I develop my next book, this course will serve as an essential background to my work on women’s readings of the Biblical text and the many uses they made of the Bible as a material book—a project for the summers to come.